What is Hyperoxaluria?

Renal calculi, or kidney stones, are solid particles that form in the kidneys due to the build-up of certain substances. Around 10% of people are affected by this, and 80% of these stones are mainly composed of calcium. The most common type of stone, calcium oxalate, mainly arises due to an imbalance in the levels of calcium and oxalate or a lack of substances that prevent the formation of these crystals. Hyperoxaluria, or too much oxalate, significantly contributes to kidney stones. The reasons for increased levels of oxalate in the urine are divided into two categories: primary and secondary hyperoxaluria, based on their cause. Even though both types can lead to kidney stones, they differ in disease severity, speed of onset, and local and general complications.

The immediate management of kidney stones is well-researched and normalized. Understanding when to further investigate a patient for potential underlying causes of these stones is crucial. This can enhance the patient’s quality of life and prevent or slow down future occurrences and other complications associated with hyperoxaluria. Generally, clinicians should offer 24-hour urine testing and preventive treatment to all patients with kidney stones, especially those who are committed to maintaining a long-term preventive treatment plan.

Even minor changes in urinary oxalate levels can significantly increase the chance of kidney stone formation. Furthermore, the presence of high oxalate levels alone, even without kidney stones, can also have harmful effects on the kidneys, leading to tubular toxicity, blockages, interstitial fibrosis (scarring), and tubular atrophy (shrinkage of the tubules in the kidneys). Unfortunately, there is currently no specific treatment for this high oxalate levels. As a result, doctors caring for these patients should familiarize themselves with available diagnostic tests and treatment options for hyperoxaluria, as well as measures to evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment.

What Causes Hyperoxaluria?

Hyperoxaluria, a condition where too much oxalate is present in your urine, can be broken down into two main categories: primary and secondary.

Primary Hyperoxaluria (PH) is less common and occurs when a person’s genes have a certain harmful mutation that leads to too much oxalate in the body. This condition tends to appear in early childhood, around the ages of 4 and 5. It often causes recurrent episodes of kidney stones and progressing kidney damage, which can result in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) if not treated.

There are three types of PH:

– PH Type I: Oxalate levels increase when a specific enzyme that breaks down a substance called glyoxalate into another substance called glycine is missing or doesn’t work effectively. If this enzyme isn’t working properly, the glyoxalate will not be converted into glycine inside liver cells and instead will build up and be converted into oxalate. This enzyme defect is linked to a specific mutation in the AGXT gene on chromosome 2. PH Type I is the most common type and is usually diagnosed around the age of 24. Approximately 80% of patients with this condition will develop ESRD by age 30.

– PH Type II: A different enzyme that converts glyoxalate to glycolate, when not working effectively, can result in oxalate accumulation. This condition is linked to a specific mutation on chromosome 10. PH Type II is milder compared to PH Type I, and around 20% to 25% of patients develop ESRD.

– PH Type III: This is the least common type of PH. It is caused by a deficiency of an enzyme that involves glyoxalate production. Symptoms are less severe than types I and II, and patients primarily present with kidney stones.

Secondary Hyperoxaluria, a much more prevalent condition, happens when a person consumes too much oxalate through their diet or due to certain intestinal conditions.

Dietary causes:

– Foods high in oxalates, like spinach, rhubarb, collard greens, nuts, beets, and tea can contribute to overproduction of oxalate in the body. Additionally, Vitamin C, if consumed in high amounts (more than 1000 mg daily), can be converted into oxalate and can increase the risk of hyperoxaluria. Similarly, cranberry juice or concentrates that are high in oxalate are not recommended for patients prone to kidney stones or hyperoxaluria due to their high oxalate content.

– Lack of dietary calcium can increase oxalate absorption and consequently induce hyperoxaluria as dietary calcium and oxalate usually bind together in the intestines and prevent too much oxalate from being absorbed.

Intestinal Causes:

– In certain intestinal conditions that lead to fat malabsorption, such as weight loss surgery or chronic diarrhea, dietary calcium binds to the unabsorbed fatty acids instead of oxalate. This results in more oxalate being absorbed into the bloodstream, leading to elevated oxalate levels in the urine.

A type of bacteria called Oxalobacter formigenes, typically found in the colon, can also play a role in this condition. If this bacteria is disrupted due to factors like antibiotic use or dietary changes, it can make hyperoxaluria worse as this bacteria normally breaks down the oxalate.

Other Causes:

– Pancreatic insufficiency in patients with acute or chronic pancreatitis can result in high oxalate absorption and therefore excretion in the urine.

– Ethylene glycol, found in antifreeze, can be accidentally or intentionally consumed and metabolized into oxalate.

– In rare cases, using certain hair treatments that contain glycolic acid have been found to cause acute kidney injury due to oxalate build-up. This might be due to the glycolic acid being absorbed through the skin and after metabolizing ends up increasing the urinary oxalate levels.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Hyperoxaluria

In developed countries, around 10% to 15% of people run the risk of getting nephrolithiasis, or kidney stones, in their lifetime. Men are more likely to get it than women, with about 10% of men and 7% of women in the United States having kidney stones. These stones can reoccur, with a 50% chance of reappearance within 10 years. More white people get kidney stones than black people.

Most kidney stones – about 80% – are made of calcium. Of these, around 75% are specifically calcium oxalate stones. Without taking preventive measures, there’s a 60% chance these types of stones will come back within ten years.

An increasingly common issue linked with kidney stones is hyperoxaluria, a condition where too much oxalate, a type of chemical, is excreted in the urine. Between 25% to 45% of people who get recurring calcium stones may have this issue. Rates are higher in Asian countries compared to Western countries due to cultural, genetic, and dietary differences. This condition also seems to be a factor in the increase of kidney stone rates worldwide.

- More research is needed on the relationship between sex hormones and oxalate production. Female hormones seem to reduce oxalate excretion, while male hormones increase it.

- Higher body weight seems to increase oxalate in urine. Both men and women with obesity tend to have higher levels.

- White people excrete more oxalate after meals rich in oxalate than Black people, possibly due to genetic factors.

A rare, specific type of hyperoxaluria, called primary hyperoxaluria (PH), usually gets diagnosed quite late, after more serious kidney issues have developed. PH type I is the most common and serious type, comprising 80% of diagnosed cases.

PH affects around 1 to 3 out of every one million people in the US. Its incidence rate is roughly one in 100,000 live births per year in Europe and one in 58,000 worldwide. It’s more common in populations with high rates of intermarriage and in developing countries. Nevertheless, PH makes up less than 1% of children with kidney diseases requiring dialysis or transplantation in the US, UK, and Japan.

Signs and Symptoms of Hyperoxaluria

Primary and secondary hyperoxaluria are conditions that can affect various age groups. They can lead to problems in the kidneys and other parts of the body. Primary hyperoxaluria is usually more severe and can affect more parts of the body than secondary hyperoxaluria.

The kidney issues related to hyperoxaluria stem from an increase in a substance called oxalate in the urine. When oxalate combines with calcium, it can form kidney stones. People typically come to the emergency room with symptoms such as severe pain in the abdomen or side that can spread to the groin, often with nausea and vomiting. They may also have trouble urinating or blood in the urine. Unlike people with other abdominal issues, those with kidney stones tend to move around trying to find a more comfortable position.

The secondary issues caused by hyperoxaluria are due to calcium oxalate spreading and gathering in other areas of the body. This occurs more often in primary hyperoxaluria or severe enteric hyperoxaluria, a type related to gastrointestinal disorders. The issues that arise depend on the part of the body affected:

- Heart: It can cause problems with the conduction of electric signals, heart blocks, and heart muscle disease.

- Blood: It can cause anemia due to oxalate deposits in the bone marrow that can’t be treated with erythropoietin-stimulating agents (ESAs).

- Nervous system: It can cause peripheral neuropathy, retinopathy, and cerebral infarcts.

- Musculoskeletal system: It can cause bone pain, pathological fractures, and issues with joints including synovitis and chondrocalcinosis. The calcium oxalate crystals forming inside tissues can be highly inflammatory and painful.

- Vascular system: It can cause non-healing ulcers and gangrene due to a lack of blood flow to blood vessels. In some cases, it has been reported to cause refractory low blood pressure.

Testing for Hyperoxaluria

If you’re experiencing intense pain in the lower back or sides, a condition known as acute renal colic, your doctor may recommend certain tests. These might include a urine test and a CT scan (a type of X-ray) of your abdomen and pelvis. These tests can help the doctor understand if kidney stones are causing your pain. If kidney stones are found, another X-ray (known as a KUB) can help track these stones over time. Stones made from calcium oxalate are usually visible if they are 2 to 3 mm or larger. Your doctor will also consider if too much oxalate (a substance naturally found in some foods) is contributing to stone formation.

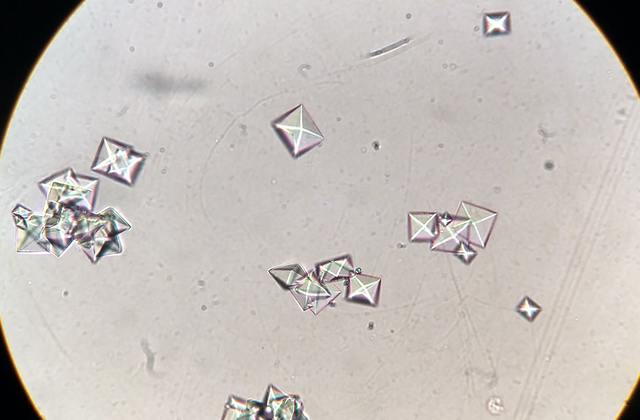

It’s important to know what your kidney stones are made of as this gives clues about why you’re getting them. Stones may be made from calcium oxalate monohydrate or dihydrate, and the specific type could hint at the root cause. Analysis of any kidney stones you have, combined with a 24-hour urine test you do at home, can determine if you’re excreting too much oxalate. This 24-hour urine test not only measures oxalate levels but also other indicators such as calcium, citrate, creatinine, and more. This comprehensive view can help identify any issues that might contribute to kidney stone formation.

The results from the 24-hour urine test should ideally show less than 40mg of oxalate in a day, with an “optimal” amount being less than 25mg. If the urine test shows 40 to 60mg of oxalate in a day, it could be due to a high-oxalate diet. Doctors also look at the ratio of oxalate to creatinine in urine, taking into account normal values for different ages. Regular repeat testing every 3 months until the levels are in control and then at least annually would be recommended.

Adapting the 24-hour urine test result for your body surface area is disputed and isn’t typically included in lab reports. Understanding how much oxalate is excreted per square meter of body surface area per 24 hours can aid diagnosis, but some experts believe this doesn’t affect stone formation.

In rare cases, someone may have a persistent, genetic condition termed Primary Hyperoxaluria (PH) which results in too much oxalate in the body. Usually, this condition isn’t diagnosed until someone develops end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and needs dialysis treatments. It might be suspected in the following situations, among others:

- A child, especially younger than 5 years, passing kidney stones.

- Recurring episodes of kidney stones in adults made of calcium oxalate.

- Urinary oxalate levels over 100mg/24 hours.

- Patients who have undergone certain types of stomach surgeries, like a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and have high oxalate levels are more likely to have secondary (diet-related) hyperoxaluria than PH.

- A diagnosis of calcium oxalate nephrocalcinosis (calcium oxalate deposits in kidney tissue), particularly if accompanied by a decrease in kidney function.

To definitively diagnose PH, doctors can use genetic tests or measure the activity of specific enzymes in a liver biopsy sample. The American Urological Association recommends genetic testing for possible PH when 24-hour urinary oxalate excretion exceeds certain limits. In the US, free genetic screening for kidney stones is available for patients, and your primary care doctor, nephrologist (kidney specialist), or urologist (urinary system specialist) can refer you for this service.

Treatment Options for Hyperoxaluria

Treating hyperoxaluria, an excessive amount of a certain substance called oxalate in the urine, usually requires both medical and surgical care. This can be coupled with care for kidney stones if present. If the kidney stones are small (less than 4mm), not passing naturally, or developing complications like infections, they can be treated conservatively with high fluid intake and medications or, if necessary, through surgery.

One of the best ways to manage hyperoxaluria is maintaining high fluid intake. Hydrating more allows your body to produce more urine which can help reduce the concentration of calcium oxalate, a primary component of most kidney stones. Instead of aiming for a specific amount of fluid intake, it’s advised to drink enough water to produce at least 3 liters of urine per day on a regular basis.

Medications like potassium citrate can help in ensuring adequate citrate levels in the urine and maintaining a desirable urine pH level. Sodium citrate may be considered in cases of kidney failure. Certain dietary adjustments can also be beneficial. Limiting intake of oxalate-rich foods like tea, dark-leafy vegetables, nuts, and chocolates is recommended. Additionally, limiting excessive intake of vitamin C is advised.

A type of vitamin B called pyridoxine is often included in treatments to help patients decrease their oxalate levels in the urine. This has been especially useful in certain genetic variations of hyperoxaluria.

Another line of treatment that has been explored is the use of a bacteria called Oxalobacter formigenes as an oral supplement. This bacteria plays a role in hyperoxaluria, however, giving it as a supplement has only shown limited benefits and experiments are still ongoing in this area.

There are also medicines that work by reducing inflammation caused by excessive oxalate. These include canakinumab, rilonacept, and anakinra, which are all approved for treatment of other conditions causing inflammation. Moreover, other medicinal substances like orthophosphates and pyridoxine, as well as magnesium supplements, have proven beneficial in treating hyperoxaluria.

The evolving world of medical science has also introduced several experimental treatments for hyperoxaluria. For example, antioxidant supplements like vitamin E, gene therapy, RNA interference therapy, hepatocyte cell transplantation, and gene-editing technology such as CRISPR. There are also plant-based therapies being investigated such as banana stem juice, lupeol, an extract from the Varuna tree, and many others. However, these are still in the early stages of research and not yet approved for widespread use.

While there is a wide range of treatment options for hyperoxaluria, it’s crucial to remember that each patient’s circumstances are unique. What works best will depend on factors like the severity of the patient’s condition, their overall health, and how their body responds to different treatments. Because of this, the treatment process often involves regular check-ups and adjustment of the treatment plan as needed.

What else can Hyperoxaluria be?

The key conditions that a doctor would consider when diagnosing kidney stones, especially calcium oxalate stones and excessive tissue deposition leading to nephrocalcinosis, include the following:

- Low amount of citrate in the urine (hypocitraturia)

- A condition that causes cysts to form in the kidneys (medullary sponge kidney)

- Excessive calcium in newborns’ kidneys (nephrocalcinosis of prematurity)

- When the kidneys fail to properly remove acid from the body (renal tubular acidosis)

What to expect with Hyperoxaluria

The outlook for a person with hyperoxaluria, a condition that causes a buildup of a substance called oxalate in the urine, depends on several factors. These include the type of hyperoxaluria, when it’s diagnosed, and how quickly treatment begins. Most people with a form of the condition called secondary hyperoxaluria can manage their symptoms through diet changes, increasing fluid intake to produce more urine, adjusting other elements in their urine through medication, and taking various supplements.

Research indicates that patients with a type of hyperoxaluria called enteric hyperoxaluria tend to fare better if they start medical treatment early and stick strictly to dietary changes. The primary treatments are medications called calcium citrate and potassium citrate, with liquid forms of these therapies generally preferred.

It’s also recommended that all other elements in the urine be adjusted for optimal health. A medication called Cholestyramine can be helpful in managing both hyperoxaluria and chronic diarrhea, which is often associated with enteric hyperoxaluria. With aggressive treatment, it is generally possible to manage the production of kidney stones, a common issue in these patients.

However, if patients develop a condition called end-stage renal disease (ESRD), where the kidneys are no longer able to work as they should, careful attention must be paid around the time of kidney transplantation and afterwards. Maintaining good urine output and keeping a close watch on oxalate levels are important in these cases.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Hyperoxaluria

The complications related to calcium oxalate stones in your urinary tract can be numerous and serious:

- Complete halt in urine production (Anuria)

- Kidney swelling due to backed up urine (Hydronephrosis)

- Inflammation of the kidney caused by a blockage (Obstructive pyelonephritis)

- Blockage after the kidney leading to decreased kidney function over time (Postrenal obstruction)

- Kidney abscess

- Leaking of urine into the body (Urine extravasation)

- Infection that spreads from your urine to your bloodstream (Urosepsis)

The most severe complication is the development of nephrocalcinosis, which can lead to a condition where the kidneys permanently stop functioning (ESRD). In addition to affecting the kidneys, long-term buildup of oxalate in the body’s fluids (serum) can also affect other organ systems. Excessive levels of calcium oxalate in the urine (Hyperoxaluria) can also lead to blockage of kidneys, inflammation of kidney tubes, atrophy (shrinking) of these tubes, and hardening of the tissue between kidneys.

Preventing Hyperoxaluria

Teaching individuals who are prone to oxalate crystallization, which can lead to kidney stones, is crucial in reducing the chances of stone formation. One of the simplest ways to prevent recurring stones is by staying hydrated and consuming enough water, as well as limiting foods high in oxalate. It’s also recommended to avoid taking vitamin C supplements. You should also reduce the amount of salt and protein in your diet alongside oxalate to lower the concentration of these substances in your urine.

Moreover, those who have secondary hyperoxaluria, which is a high concentration of oxalate in the urine, or an underlying cause for steatorrhea, which is an excess of fat in the stool, should consume a low-fat diet. This helps prevent calcium ions from getting trapped in fat, which can then increase the absorption of oxalate, a substance that can contribute to kidney stone formation.

As for patients with Primary Hyperoxaluria (PH), a rare condition where there is an overproduction of oxalate leading to kidney stone disease and kidney failure, the condition tends to be passed down through families (known as autosomal recessive inheritance). Therefore, it’s important for these individuals to seek genetic counseling to better understand the risks and implications.