What is Renal Angiomyolipoma?

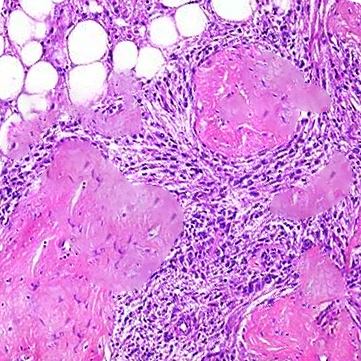

Renal angiomyolipomas are the most common types of benign, or noncancerous, kidney tumors. These tumors were first described by a scientist named Grawitz in 1900 and are highly vascular, meaning they have many blood vessels. They are mostly made up of blood vessels, smooth muscles, and mature fat tissues. Located around blood vessels, these tumors can often be found unexpectedly during routine radiological imaging. However, they can also cause symptoms like side body pain, visible blood in urine, or severe bleeding in the space behind the lower abdomen.

It’s worth noting that sometimes angiomyolipomas and hamartomas, another type of benign tumor, are confused with each other. The main difference is that while both are benign, angiomyolipomas are true tumors while hamartomas are disorganized growths of normal tissue often caused by trauma, infection, or bleeding. More importantly, angiomyolipomas should not be confused with Grawitz tumors, which are malignant or cancerous kidney tumors, also known as renal cell carcinomas and hypernephromas.

Scans and imaging are crucial in correctly diagnosing and managing renal angiomyolipomas. These tumors contain different amounts of blood vessels, muscle, and fat tissue, which create unique appearances on scans and specific clinical symptoms. The key to diagnosing a classic angiomyolipoma is to find a significant amount of fat tissue on the scans.

While these tumors are typically benign, they can sometimes grow into the fat surrounding the kidney or the kidney sinus, nearby organs, and lymph nodes. There have also been rare reports of the tumor extending through the kidney vein into the large vein that carries blood from the lower half of the body back to the heart, called the vena cava.

The treatment approach for angiomyolipomas depends on several factors including symptoms, the size, number and growth pattern of the tumors, and the possibility of them becoming malignant or cancerous. For example, a rare subtype called epithelioid angiomyolipoma of the kidney is considered to potentially turn malignant.

What Causes Renal Angiomyolipoma?

Renal angiomyolipomas are conditions mainly appearing in two ways – isolated or “sporadic cases” (80% of occurrences) or associated with certain inherited conditions (20% of occurrences) like tuberous sclerosis and pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. The exact reason for the isolated cases isn’t known, but some scientists reckon that it may be a result of random genetic changes.

Inherited angiomyolipomas linked to tuberous sclerosis complex or pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis are triggered by genetic changes in the genes TSC1 or TSC2. These changes affect a natural substance in our bodies called the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which is why medical treatments that target mTOR, like sirolimus and everolimus, can help patients.

In comparison to more common isolated cases, inherited angiomyolipomas that are linked to tuberous sclerosis or lymphangioleiomyomatosis usually start earlier, grow faster and larger, are more prone to bleeding, may contribute to long-term kidney diseases and are more likely to turn malignant or cancerous.

Causes of Renal Angiomyolipomas

Tuberous sclerosis is a rare inherited genetic condition where benign (non-dangerous) tumors grow in different body parts like the brain, eyes, heart, lungs, and kidneys. It is also linked to skin conditions (adenoma sebaceum), epilepsy, and mental deficiencies. Even though it’s not common, happening in about 1 in every 10,000 people, the real number of people suffering from it is likely much higher. Over 50% of people with tuberous sclerosis eventually go on to develop renal angiomyolipomas.

This condition is usually diagnosed by the discovery of benign tumors in the brain, kidneys, heart, liver, and lungs. It’s associated with various skin conditions and can cause various symptoms such as seizures, mental deficiencies, autism, behavioral challenges, learning disabilities, and developmental delays. A definitive diagnosis can be made through genetic testing.

People with tuberous sclerosis usually have larger renal angiomyolipomas, are more likely to have them in both kidneys and more sites, and have a higher chance of these tumors growing over time compared to those without tuberous sclerosis.

Pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis is an extremely rare genetic disorder often linked to angiomyolipomas and sometimes with tuberous sclerosis. The condition typically affects women of childbearing age, causing abnormal growth of smooth muscle cells in the lungs, which can affect a patient’s ability to breathe.

Pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis can cause cysts in the lungs and is also associated with kidney angiomyolipomas. It should be suspected in younger women with diseases affecting the tissue and space around the air sacs of the lungs. Diagnosis of this condition can be confirmed through biopsy or elevated levels of vascular endothelial growth factor-D (VEGF-D), a type of protein that can indicate disease.

People newly diagnosed with lymphangioleiomyomatosis should undergo kidney tests to look for angiomyolipomas. However, routine testing for lymphangioleiomyomatosis in most female patients with angiomyolipomas isn’t typically done due to its rarity. Nonetheless, it should be considered in younger women with multiple kidney angiomyolipomas, especially if they also have lung problems.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Renal Angiomyolipoma

Renal angiomyolipomas are uncommon kidney tumors that make up just 0.3% to 3% of all kidney tumors. They are relatively rare, occurring in 0.13% to 2.2% of the population, with 80% of cases happening randomly. The remaining 20% are associated with conditions like pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis and tuberous sclerosis complex.

These tumors tend to occur more often in females than males, possibly due to the effects of estrogen. They also tend to be larger in females. Pregnant women face a higher growth rate of these tumors and a higher risk of bleeding complications. Similarly, taking extra estrogen as part of medical treatment appears to increase the risk of bleeding from these tumors.

- Renal angiomyolipomas are rare kidney tumors, making up only 0.3% to 3% of all kidney tumors.

- 80% of these cases occur randomly, with the remaining 20% being associated with specific conditions.

- They occur more often in females, and can be larger in size in females than males.

- Pregnant women have a higher risk of these tumors growing rapidly and bleeding.

- Treating with extra estrogen can also increase the risk of bleeding from these tumors.

- 50% to 75% of individuals with tuberous sclerosis will develop renal angiomyolipomas, and the tumors tend to appear at a younger age in these individuals (12 years old) compared to those without the condition (24 years old).

Signs and Symptoms of Renal Angiomyolipoma

Renal angiomyolipomas are often silent conditions, meaning they usually don’t show any symptoms and are often identified by accident during imaging procedures like ultrasounds or CT scans. The improved accuracy of these imaging technologies has made it easier to detect such cases.

In the past, around 15% of patients were diagnosed because they experienced a spontaneous bleeding in the back of the abdomen, a condition known as Wunderlich syndrome. This can sometimes be severe, causing shock in about a third of cases. Thus, the main concern for someone newly diagnosed with a renal angiomyolipoma is the risk of severe, potentially life-threatening bleeding. While other kidney diseases like cancer or cysts can also cause this type of bleeding, renal angiomyolipomas are the most frequent cause.

Some possible signs and symptoms of this condition include:

- Flank pain

- Noticeable lump in the abdomen

- Urinary tract infections

- Blood in the urine (hematuria)

- Anemia

- Severe kidney issues

- Shock

Generally, renal angiomyolipomas are benign, meaning they typically don’t become life-threatening or cancerous. However, a specific kind, called the “epithelioid” variant, can potentially become malignant.

Renal angiomyolipomas associated with genetic conditions like tuberous sclerosis complex or pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis can be more aggressive. They usually appear earlier in life, are more likely to affect both kidneys and have multiple affected areas, and are often bigger at the time of diagnosis compared to other varieties of this condition.

Testing for Renal Angiomyolipoma

Renal angiomyolipomas are a type of kidney tumor that can vary in how much fat they contain. About 5% of these tumors don’t have much, or any, visible fat.

Doctors often find these tumors when doing a CT scan for other reasons, but if the results of the CT scan aren’t clear or more information is needed, an MRI is typically the next step. An MRI is particularly good at spotting fat-poor angiomyolipomas. One downside of CT scans is that they can’t always identify tumors without much visible fat, requiring either a biopsy or surgery to confidently diagnosis.

Diagnostic imaging – taking a closer look inside the body – is the best way to identify these tumors. Usually, a biopsy, where a small tissue sample is taken for closer examination, isn’t needed, but it might be used to rule out cancer if the case is complex.

There are various ways to get images of the kidney to diagnose renal angiomyolipomas:

Ultrasound: This method is often not clear enough to make a diagnosis, but it is very useful for monitoring known tumors because it’s affordable and doesn’t expose the patient to radiation. If, however, the ultrasound shows significant growth or a potentially serious change, doctors usually turn to a CT scan or MRI.

Computed tomography (CT scanning): CT scans are usually the first choice for taking a closer look at such tumors. Depending on where the scan is placed, it may show fat-rich angiomyolipomas, which contain a lot of fatty tissue, or fat-poor angiomyolipomas, which don’t. For tumors without much visible fat, an MRI may be called for.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRIs are excellent at showing fat-poor tumors and are preferred for use on children because there’s no radiation exposure. In one study, 90% of fat-poor tumors could be diagnosed with an MRI. However, if the results are still not clear, a biopsy may be required.

Percutaneous biopsy: This is a type of biopsy where a thin needle is inserted through the skin to take a sample. They’re generally not used much because imaging usually provides good results and they can cause bleeding. But in some cases where it’s very hard to tell if the mass is a benign angiomyolipoma or cancer, especially when both MRI and CT scanning don’t provide clear results, a biopsy may be necessary.

Overall, while ultrasound can be helpful, it cannot be relied upon for a clear diagnosis. CT is usually the first go-to imaging method, and if it doesn’t produce clear results, an MRI is the next step. If neither of these methods can clearly identify the mass, it is typically treated as kidney cancer to be on the safe side.

Treatment Options for Renal Angiomyolipoma

Angiomyolipoma is usually a silent, non-dangerous tumor that often doesn’t need treatment. However, in some cases, treatment may be necessary. Earlier, doctors used to treat tumors over 4 cm in size, but recent studies revealed that only a few of these larger tumors cause symptoms. Bursting of the blood vessels in the tumor (aneurysm) larger than 5 mm can lead to a higher risk of bleeding, rather than the size of the tumor alone.

So, nowadays, doctors consider factors like the blood flow in the tumor, the presence of aneurysms, and symptoms to decide if a patient needs treatment. For instance, pregnant women, women of childbearing age, people with jobs in high-risk industries, and those with larger tumors are usually considered for treatment. In pregnant women, angiomyolipomas can grow rapidly, leading to a higher risk of bleeding, due to increased estrogen levels.

Doctors may use medication, thermal therapies, minor surgical techniques, and surgical removal as possible treatments for angiomyolipoma. The choice of treatment depends on each patient’s specific case.

Medications such as sirolimus and everolimus can help shrink tumors. They are especially effective in patients with genetic conditions like tuberous sclerosis or pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. These drugs work by slowing down the rate of cell growth, which is typically uncontrolled in these genetic conditions.

Thermal ablative therapies like radiofrequency ablation and cryotherapy use heat and cold, respectively, to destroy the tumor. They are minimally invasive procedures and can treat small to large tumors with minimal damage to healthy kidney tissue.

Selective renal artery embolization is a minimally invasive procedure that is considered the first choice of treatment for angiomyolipoma. This procedure involves inserting a catheter into the blood on the leg and directing it towards the tumor to stop the blood supply and shrink it. However, this procedure may cause side effects like flank pain, fever, vomiting, nausea, and an increase in white blood cells. It might also need to be repeated if the tumor grows back.

Surgical removal of the tumor is the most definitive form of treatment. Surgeons try to spare as much healthy kidney tissue as possible during the surgery, especially in patients with hereditary angiomyolipomas who have a higher chance of developing new tumors. The surgical option is usually considered when there’s a high suspicion of cancer, the tumor is very large, or the other treatments are not possible.

For patients who don’t show any symptoms, doctors usually monitor the tumor’s progression with regular imaging studies like ultrasound, CT scan, or MRI, depending on the patient’s specific condition.

What else can Renal Angiomyolipoma be?

Identifying the different types of kidney tumours known as renal angiomyolipomas is important. These tumours come in different types – ones that have a lot of fat, ones that have very little fat, and ones where the fat is not visible. Those with a lot of fat can be easily spotted on scans because of the high fat content in the tumour. However, it is hard to accurately diagnose tumours where there is little or no visible fat.

Before deciding on a treatment, doctors need to rule out other possible medical conditions that might look like renal angiomyolipoma. These can include other conditions that can affect the kidneys and adrenal glands such as adrenal myelolipoma, oncocytoma, kidney cancer, or retroperitoneal liposarcoma. Other conditions doctors might consider include metastatic tumours that have spread to the kidney and a certain type of kidney tumour seen in children, known as Wilms tumor.

With today’s advanced scanning techniques, doctors are finding more and more small tumours in the kidneys. These are often found by chance, and many of them are initially thought to be kidney cancers. However, in around 22% of these cases, these tumours turn out to be non-cancerous after surgery, with renal angiomyolipomas making up about half of these benign cases.

Distinguishing between kidney cancers and angiomyolipomas can be difficult in normal medical practice, especially when the angiomyolipoma has little or no visible fat. There are some clues doctors look for though. These include being female, younger, and not having symptoms. Certain features seen on scans can also suggest angiomyolipoma, such as the presence of multiple lesions and certain appearances on MRI and CT scans. However, these are not always reliable, and no single symptom or scan result is definitive.

Another condition that could look similar on scans is retroperitoneal liposarcoma. But whereas angiomyolipomas usually present with a small dent or dimple where the tumour started, liposarcoma tends to wrap around and compress the whole kidney without a clear starting point.

While some angiomyolipomas can grow quickly, most grow slowly. A rapid increase in size, more than 5mm per year, can raise concerns about potential cancer. If a lesion does not respond to certain drugs (mTOR inhibitors), this can also raise suspicion. Lesions that are thought to be cancerous, which have features such as areas of dead tissue, calcium deposits, swollen regional lymph nodes, spread to other body parts, or encroachment on the tissue surrounding the kidney, will usually need to be removed by surgery unless a needle biopsy proves they are benign.

What to expect with Renal Angiomyolipoma

Small angiomyolipomas, which are non-cancerous kidney tumors, often have a good outcome because there’s a low chance of unexpected bleeding, estimated at about 2%. However, angiomyolipomas in the kidneys that have large bulges in the blood vessels (larger than 5 mm) or those that are larger than 6 cm in size carry a significant risk of spontaneous rupture and bleeding, which can be a life-threatening situation.

Besides this, certain types of angiomyolipomas can potentially turn malignant or cancerous, serving as another important factor to consider when checking their future outcomes. These types may have a higher likelihood of this transformation.

Fresh clinical guidelines are important to help doctors decide the best way to manage these uncommon and abnormal cases. To make progress in treatments or potential cures, continuous exploration in the fields of genetics, immunotherapy, and other new treatment methods will be needed.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Renal Angiomyolipoma

Even though renal angiomyolipoma is a rare, non-cancerous kidney tumor, it can still cause serious health problems and potentially lead to death. This is due to the tumor’s unique blood vessel features and possible complications from treatment.

One of the main risks related to this type of kidney tumor is bleeding. Studies have consistently found that larger tumors (more than 6 cm in size) and tumors connected to the complex condition called tuberous sclerosis, are more susceptible to bleeding than smaller, individual tumors. This highlights the need for preventive treatment.

Furthermore, renal angiomyolipomas can gradually lead to kidney damage over time.

- Renal angiomyolipoma is a rare, non-cancerous kidney tumor, but may lead to serious health problems and potentially death.

- Increased risk of bleeding with larger tumors and those associated with tuberous sclerosis complex.

- Potential for renal impairment over time.

Preventing Renal Angiomyolipoma

People with renal angiomyolipoma, a typically non-cancerous kidney tumor, should be aware that this condition is typically not harmful. Doctors and healthcare professionals will explain that available medications and minimally invasive treatments can stop the disease from advancing and reduce the chance of spontaneous bleeding. It’s important to take medicine as directed and keep up a regular check-up schedule for the long term to manage the condition effectively.

Women who could become pregnant and who have been diagnosed with renal angiomyolipoma need to plan ahead. It’s crucial to discuss your condition and its management with your healthcare provider before getting pregnant, as pregnancy can lead to the growth, and possibly rupture, of the tumor. This growth could heighten one’s risk for disease progression and complications. Thus, it’s a significant factor to consider.