What is Acute Pulmonary Embolism (Pulmonary Embolism)?

A pulmonary embolism (PE) happens when a blood clot blocks the lung’s main artery or its branches. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is when a blood clot forms in the deep veins, most often in the lower part of the body like the legs. A PE usually happens when a piece of this blood clot breaks off and travels to the lungs. Other things, like air, fat, or even cancer cells, can also cause a PE, but it’s really rare. When you have both PE and DVT, it’s referred to as venous thromboembolism (VTE).

What Causes Acute Pulmonary Embolism (Pulmonary Embolism)?

The causes and risk factors for a type of lung blockage known as Pulmonary Embolism (PE) are similar to those of a leg clot, called a Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT). These can be understood through what’s called Virchow’s triad, which includes three factors: a higher tendency for blood clotting, slow blood flow in the veins, and damage to the lining of blood vessels.

Risk factors can be of two types: genetic and acquired. Genetic factors relate to blood conditions that can make clotting more likely. These include mutations in factors V Leiden and prothrombin genes, deficiencies in proteins C and S, and high levels of homocysteine.

Acquired risk factors involve changes in lifestyle or health status. Key examples here include staying immobile for over 3 days or traveling for over 4 hours, recent surgery on bones, having cancer, having a venous catheter, being overweight, being pregnant, smoking, and using birth control pills.

Certain situations can increase the risk of vein clotting (VTE) which include bone fractures of the lower limb, being hospitalized within the last 3 months due to heart failure or irregular heartbeat, hip or knee replacements, serious injuries, a history of VTE, having a central venous line, undergoing chemotherapy, hormone replacement therapy, post-childbirth, infections like pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and HIV, cancer (highest risk if cancer has spread), clotting disorders, prolonged bed rest, obesity, and pregnancy.

Cancer in certain areas like the pancreas, blood, lungs, stomach, and brain, can place individuals at high risk for clot formation and hence PE. Additionally, any infection can often trigger VTE. Heart-related conditions like a heart attack or heart failure can also heighten PE risk. Those with a history of VTE are at an increased risk of suffering a stroke or heart attack.

Pulmonary Embolism is categorized based on how it affects circulation and blood pressure. A type of PE which leads to low blood pressure and requires treatment to elevate it is called Hemodynamically Unstable PE. This does not refer to the size of the PE, but its effect on blood flow and pressure. These individuals are more likely to die from a blockage that causes severe failure of the right side of the heart.

On the other hand, Hemodynamically Stable PE is a type of PE which doesn’t result in a significant drop in blood pressure and ranges from small, mildly symptomatic, or symptomless PEs to PEs that initially cause low blood pressure but stabilize with fluid therapy.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Acute Pulmonary Embolism (Pulmonary Embolism)

Pulmonary embolism, or PE, affects between 39 to 115 out of every 100,000 people each year. It’s the third most common type of cardiovascular disease, following coronary artery disease and stroke. It occurs more frequently in males than in females. PE is a serious condition and can be fatal. In the United States alone, it causes about 100,000 deaths every year. But, figuring out the exact death rate from PE is difficult because many sudden cardiac deaths may be due to PE. Luckily, the death rates from PE have been decreasing, possibly due to advancements in diagnosing and treating the condition.

- Pulmonary embolism, known as PE, affects 39 to 115 per 100,000 individuals each year.

- It ranks as the third most frequent cardiovascular disease, after coronary artery disease and stroke.

- PE is seen more often in men compared to women.

- In the United States, PE results in roughly 100,000 deaths annually.

- Pinpointing the exact death rate from PE is challenging as many sudden heart-related deaths might be due to PE.

- Death rates from PE have been reducing, likely due to improved methods in diagnosis, early treatment, and therapies.

Signs and Symptoms of Acute Pulmonary Embolism (Pulmonary Embolism)

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a serious condition that can have life-threatening consequences if not treated promptly. It’s critical to diagnose and treat PE quickly as it can be fatal for about 30% of patients if untreated. However, if treated in a timely manner, the fatality rate drops to 8%. Identifying PE can be challenging as it can cause a variety of symptoms that aren’t specific to this condition. Common symptoms include shortness of breath, chest pain, cough, coughing up blood, fainting or near fainting.

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain

- Cough

- Coughing up blood

- Fainting or near fainting

These symptoms can vary in severity depending on how big the embolism is. Sometimes, a person who already has heart failure or a lung disease might only experience worsening shortness of breath. Not all patients with PE have symptoms, or they may only have mild symptoms.

Symptoms of PE can sometimes also include irregular heart rhythms, fainting, and a sudden drop in blood pressure. If the embolism is large or in a key location within the lung, it can be critical and result in shock or even cardiac arrest. PE should be suspected in anyone with low blood pressure and distended neck veins, once heart attacks, fluid around the heart, or a punctured lung have been ruled out.

PE usually results from blood clots in the legs, so during an examination, doctors will also look for common signs such as rapid breathing, rapid heart rate, swelling or redness in leg, and signs of high blood pressure in lungs like elevated neck veins.

- Rapid breathing

- Fast heart rate

- Swelling or redness in leg

- Elevated neck veins implying high blood pressure in lungs

If there’s a sudden drop in heart rate or newly starting erratic heartbeat with one type of heart block, it might imply that the right side of the heart is under strain and that shock might be imminent.

Testing for Acute Pulmonary Embolism (Pulmonary Embolism)

If a person is experiencing unexplained shortage of breath with a normal chest x-ray, it raises suspicions of a potentially severe lung problem known as a pulmonary embolism (PE). A specific marker of this condition is a widened gap between inhaled and exhaled oxygen, quick breathing that might cause a decrease in carbon dioxide levels in the blood, and increased blood pH levels. Usually, carbon dioxide and acid build-up are not common in PE situations, but they may appear in severe cases of PE.

Certain protein levels in your body can help determine the severity of PE. Elevated Brain Natriuretic Peptide (BNP) levels could imply a higher severity of PE, due to a higher stretch on your heart. However, this condition doesn’t often help in diagnosing PE by itself.

Further, troponin, a protein present in your blood, is not necessary for diagnosing PE, but it is beneficial for determining patient prognosis. It helps estimate the dysfunction of the right chamber of your heart. Approximately 30% to 50% of PE patients experiencing medium to large PE might have elevated troponin levels. This condition also is linked to worsening health and death due to PE.

D-dimer, another protein in your blood, can help identify an ongoing clotting process in your body. It can rule out PE with a high negative predictive value if the D-dimer level is normal. However, it is not useful for confirming PE.

D-dimer levels should be adjusted for age, as they decrease with age. For patients older than 50 years, it is suggested to multiply the age by 10 to get a more relevant D-dimer cut-off value.

Apart from lab tests, imaging techniques can also provide useful insight when diagnosing PE.

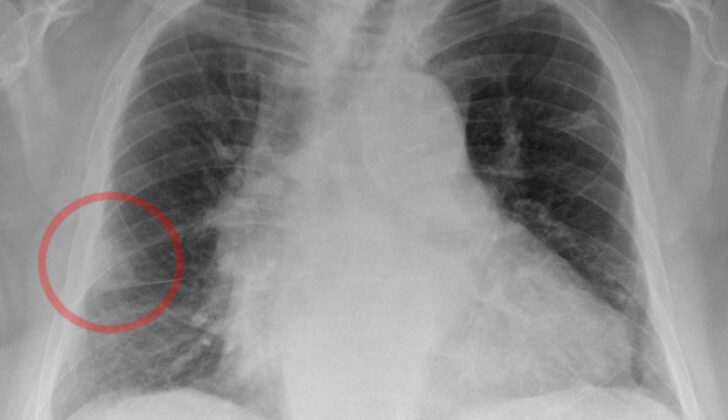

An ECG (electrocardiogram) can show certain non-specific changes and faster heartbeat, but these are not exclusive to PE and might be present in other conditions too. Chest X-ray might be normal for PE patients, or it might show nonspecific findings like shortness of breath or fluid accumulation. It can help doctors to rule out other possible explanations for acute shortness of breath.

CTPA (Computed Tomographic Pulmonary Angiography) is often used as the primary way to diagnose PE. It can show detailed images of pulmonary arteries. But, its accuracy could vary depending on the clinical probability of the disease.

Although primarily used for treatment rather than diagnosis, pulmonary angiography, a procedure in which a special dye is injected into lung arteries, can also give a direct visual of a clot if present.

Another imaging technique, MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging), can provide images of PE, but it is not often used as the first step of diagnosis due to its low sensitivity and less availability.

Echocardiography can helps estimates the strain on the right side of your heart, which can indicate PE. But it can rarely provide definitive proof of a clot in the pulmonary arteries. It’s used mostly for patients with severe symptoms and can be useful for justifying the emergency use of clot-dissolving therapy.

Finally, compression ultrasound can identify blood clots forming in your legs that can potentially travel to your lungs. It is a crucial step when other preferred imaging methods are contraindicated or give unclear results.

Doctors often use scoring systems like Wells criteria or Geneva score to assess the probability of PE based on multiple factors. They categorize patients based on these scores. Certain rules are also used to rule out PE in patients with mild symptoms, for example, PERC (Pulmonary Embolism Rule-out Criteria).

In conclusion, a combination of physical examination, specific lab tests, various imaging techniques, and scoring systems are all used in diagnosing PE patients to provide an accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

Treatment Options for Acute Pulmonary Embolism (Pulmonary Embolism)

The first step in managing patients with pulmonary embolism, or PE, is to stabilize the patient. If a patient’s blood oxygen levels are below 90%, they should receive extra oxygen. Those patients who are very unstable may need mechanical ventilation, where a machine helps them breathe.

It’s important to understand that severe Right Ventricular failure can be a major cause of death in patients with unstable PE. Giving these patients large amounts of volume can overload the right ventricle, making the situation worse, so this should be avoided unless the patient lacks enough volume.

In situations where PE makes a patient unstable, certain devices like extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO, can be used to help support the heart and lungs.

Anticoagulation, or blood thinning, is the main treatment for acute PE. We normally use low-molecular-weight heparin and fondaparinux because they’re less likely to cause significant bleeding and a low platelet condition known as heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. We typically use unfractionated heparin for unstable patients who might need busting out the clot or in patients with poor kidney function. Other drugs like newer oral anticoagulants and vitamin K antagonists can also be used.

The approach to treating patients with PE depends on whether they are stable or unstable and how likely it is that they have PE.

For those who are stable and highly likely to have PE, blood thinning should start before any imaging tests. If there’s only a low suspicion for PE and imaging can be done within a day, then wait for test results before starting treatment. If it’s likely they may have PE and imaging can be done within four hours, then wait for the results. If blood thinning is not suitable, filters to catch clots are an option.

In unstable patients with high suspicion of PE, immediate imaging is required and clot-busting drugs are usually the first choice for treatment. If these drugs can’t be given, surgical removal of the clot or use of a catheter to directly treat the clot are options. After stabilization, the patient can then be switched from injectable to oral blood thinners.

Clot-busting drugs are effective in reducing the pressure and resistance in the pulmonary arteries when given within 48 hours of symptom onset. However, they also increase the risk of severe bleeding. Procedures using catheters to treat the clot directly are successful in many patients but carry the risk of perforating the pulmonary arteries, which could cause catastrophic bleeding. Permanent filters are effective in reducing the risk of recurrence but increase the risk of blood clots in the legs.

After the first episode of PE is managed, the aim of continued anticoagulation treatments is to prevent recurrence. In analysing various studies, all patients with PE should be treated with blood thinners for at least 3 months. After stopping anticoagulation, the risk of recurrence is expected to be similar whether treatment was continued for 3 to 6 months or longer. After stopping treatment, the risk of recurrence doesn’t disappear.

It’s noteworthy that nearly 30% of all PE are unprovoked, and these cases carry a two to three times higher risk of recurrence than in patients with identifiable risk factors. If a PE was unprovoked or persistent risk factors exist, longer anticoagulation therapy may be necessary. In cancer patients with PE, specific types of blood thinners, such as LMWH, apixaban, and rivaroxaban, may be preferred over VKA.

What else can Acute Pulmonary Embolism (Pulmonary Embolism) be?

The symptoms of Pulmonary Embolism, also known as PE, can vary greatly. They can range from shortness of breath to sudden cardiac arrest. Because of this wide range of symptoms, it is often confused with other health conditions. Therefore, doctors consider these possibilities before making a diagnosis:

- Acute Coronary Syndrome, a sudden blockage in the blood supply to the heart

- Stable Angina, a type of chest pain caused by reduced blood flow to the heart

- Acute Pericarditis, the inflammation of the pericardium

- Congestive Heart Failure, when the heart can’t pump blood effectively

- Malignancy, existence of a harmful or potentially harmful cells in the body

- Cardiac Arrhythmias, irregular heartbeat

- Pneumonia, an infection that inflames air sacs in one or both lungs

- Pneumonitis, inflammation of lung tissue

- Pneumothorax, a collapsed lung

- Vasovagal Syncope, sudden loss of consciousness caused by a sudden drop in heart rate and blood pressure leading to fainting

What to expect with Acute Pulmonary Embolism (Pulmonary Embolism)

Shock and issues with the right ventricle of the heart are often signs of a grim prognosis and increased chance of death in patients diagnosed with a pulmonary embolism (PE). The risk of death can also increase if the patient also has a deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Many models can predict these risks, but the two most commonly used are the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (PESI) and a simpler version of it (sPESI).

Both PESI and sPESI are mainly used to identify patients who are at a low risk of dying within 30 days of a PE diagnosis.

The original and simplified versions consist of several factors. Each factor corresponds to a certain number of points. The factors and their corresponding points are as follows:

- Age: 1 point if over 80 years

- Male: 10 points in PESI, none in sPESI

- Cancer 30 points in PESI, 1 point in sPESI

- Chronic heart failure: 10 points in PESI, 1 point in sPESI

- Chronic lung disease: 10 points in PESI, 1 point in sPESI

- Pulse rate over 110 beats per minute: 20 points in PESI, 1 point in sPESI

- Blood pressure lower than 100: 30 points in PESI, 1 point in sPESI

- Breathing rate more than 30 breaths per minute: 20 points in PESI, none in sPESI

- Altered mental status: 60 points in PESI, none in sPESI

- Low blood oxygen saturation: 20 points in PESI, 1 point in sPESI

These points are then used to assign patients to risk classes with corresponding mortality rates in PESI:

- Class I: Under 65 points; 1% to 6% risk of death within 30 days.

- Class II: 66 to 85 points; 1.7% to 3.5% risk of death within 30 days.

- Class III: 86 to 105 points; 3.2% to 7.1% risk of death within 30 days.

- Class IV: 106 to 125 points; 4% to 11.4% risk of death within 30 days.

- Class V: Over 125 points; 10% to 24.5% risk of death within 30 days.

Meanwhile, in sPESI, it’s simpler to predict death risks. If a patient scores 0 points, their risk of dying within 30 days is 1%. If they score 1 or more points, the risk jumps to 10.9%.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Acute Pulmonary Embolism (Pulmonary Embolism)

Pulmonary embolism (PE) can lead to severe complications, such as repeated clot formation (recurrent thromboembolism), chronic high blood pressure in the lungs (chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension), failure of the right side of the heart (right heart failure), and a life-threatening state where the heart can’t pump enough blood to the body (cardiogenic shock). If PE is not treated, it can cause death in up to 30% of cases. There’s also evidence that it can increase a patient’s risk of stroke, which may be due to clots unexpectedly moving to the brain through a small hole in the heart called a patent foramen ovale (PFO).

- Recurrent Thromboembolism: In the first couple of weeks after PE diagnosis, if a patient’s symptoms get worse or the condition comes back, it may typically be due to insufficient use of blood thinners, which are supposed to hinder clot formation.

- Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension (CTEPH): If patients still feel breathless (dyspnea) months, or up to two years after a PE episode, especially if the symptoms are persistent, doctors should investigate the possibility of CTEPH (which affects about 5% of patients). Various imaging tests such as CT scans, ventilation-perfusion scans, or echocardiograms may be performed. These tests can help determine if the blood pressure in the lungs is high (indicative of CTEPH). Patients generally tend to show some abnormalities in their lung scans, which calls for further assessment and tests to confirm CTEPH, identify the severity, rule out any other medical conditions, and determine the possibility of surgical intervention. Regardless, all patients diagnosed with CTEPH will likely need lifelong anticoagulant (blood thinner) therapy and should be assessed for possible surgery.

Recovery from Acute Pulmonary Embolism (Pulmonary Embolism)

People who have survived Pulmonary Embolisms (PEs) often show a decrease in various functions including breathing capacity, resilience during exercise, and overall quality of life. About half of these survivors continuously experience symptoms that decrease their physical potential. Ongoing research is necessary to pinpoint risk factors that make certain individuals more susceptible to significant function loss after overcoming a PE.

Different studies have recommended varying rehabilitation strategies after a PE, along with varied beginning times, which can span from weeks to months after diagnosis. These studies highlight that the risks are minimal, with benefits that include notable reduction in breathlessness, and improvements in exercise ability, daily movement, and life satisfaction.

It’s important for rehabilitation services to closely coordinate with other healthcare teams to identify the lost functions and design a patient-specific plan to safely overcome these shortcomings.