What is Aspiration Pneumonia?

Aspiration pneumonia is a lung infection that occurs when fluids filled with bacteria from the throat get into the lower part of the lungs. The infection could also be caused by inhaling particles or stomach content. This condition is commonly seen in older adults and can be particularly risky for people with learning disabilities or those with gastrointestinal or neurological disorders, as they are more likely to have difficulties swallowing.

Aspiration pneumonia can be picked up either within the community or hospitals and clinics. Its definition isn’t exact, but according to a recent study, diagnosing aspiration pneumonia relies on spotting lung inflammation in patients who clearly have aspiration, difficulty swallowing, or medical conditions linked with these symptoms. The disease process involves bacteria from the inhaled fluid spreading into the lung tissue.

Aspiration pneumonitis, on the other hand, differs from aspiration pneumonia. Even though both these conditions result from aspiration, aspiration pneumonitis occurs when a non-infectious chemical lung injury happens from inhaling sterile fluid or stomach content.

Healthcare professionals should always suspect aspiration pneumonia in patients who are at a higher risk to ensure proper diagnosis and to prevent complications. The problem is, there isn’t enough detailed guidance on this topic in the medical literature. Furthermore, it can be very challenging to definitely diagnose aspiration pneumonia, especially if the patient has experienced several small aspirations. The treatment methods for patients with aspiration pneumonia have also changed, highlighting the importance of educating healthcare workers about how this disease typically presents, how to diagnose it, and the different treatment options available.

What Causes Aspiration Pneumonia?

Normally, our bodies stop aspiration pneumonia from happening thanks to natural defense mechanisms like closing the windpipe and coughing. However, when these mechanisms fail, the risk of getting aspiration pneumonia increases. Several factors can contribute to this risk, including issues like altered mental state, neurological conditions, problems with the esophagus, consistent vomiting, and blockage in the stomach’s outlets.

Many conditions can raise the risk of aspiration in adults: firstly, being of an advanced age can be a factor. Other conditions include post-stroke pneumonia, drug overdose, alcohol use disorder, seizures, use of sedative medication, and central nervous system disorders such as brain trauma, internal brain masses, dementia, and Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Diseases like multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, Pseudobulbar palsy, muscular conditions like inflammatory myopathies, bulbospinal muscular atrophy, oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy, and others can also increase the risk. Limited mobility, esophageal strictures, mobility disorders, cancers, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and procedures like tracheostomy and nasogastric tube placement may also add to the risk of developing aspiration pneumonia.

Being older can significantly increase the risk of aspiration pneumonia since many elderly people unknowingly experience little inhalations of food, liquid, or saliva into their lungs. It should be noted that while age does contribute, reasons such as frailty, poor nutrition, and reduced mobility are considered more reliable indicators of the risk in older people.

The prevalence of aspiration pneumonia can differ in different patient groups. In people who have had a stroke, 3% to 50% can get aspiration pneumonia. The occurrence of silent aspiration in those who have had a stroke can range from 40% to 70%. Hospitalized patients with conditions like Parkinson’s disease or dementia can experience up to 11% rates of aspiration pneumonia over 3 months. It’s also common amongst patients with multiple sclerosis, motor neuron diseases, Huntington’s disease, Down syndrome, and cerebral palsy.

People with head, and neck cancers and those who undergo their treatment also have an increased risk of developing aspiration pneumonia, with up to 70% of patients experiencing it in their lifetime.

The amount and type of bacteria present in the mouth can also strongly contribute to the risk. Even a small inhalation into the lungs can lead to infection if there are lots of bacteria present. Studies have shown that poor oral health can be a significant risk factor for pneumonia, including for patients in hospitals.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Aspiration Pneumonia

Aspiration pneumonia differs from person to person and is diagnosed differently by each doctor, which makes understanding its true incidence difficult. The information available indicates that up to 20% of people in the US have some difficulty swallowing, which leads to about 0.4% of all hospital admissions. This issue is associated with aspiration pneumonia. In the case of pneumonia contracted outside the hospital, the instances of aspiration pneumonia are between 5% and 15.5% in the US, UK, and Korea. However, in Japan, the rates are significantly higher at 60% for community-acquired pneumonia patients and even higher for those with pneumonia contracted in the hospital.

Nonetheless, not everyone who aspirates gets pneumonia. Among patients under 80 years old, swallowing something into the lungs leads to pneumonia only 5% of the time. This percentage increases to 10% for those over 80 years old. Interestingly, among nursing home residents diagnosed with pneumonia, 18% to 30% of the cases are associated with aspiration. In cases involving anesthesia, up to 64% of those who aspirate show no signs of infection afterwards either visually or on x-rays.

Signs and Symptoms of Aspiration Pneumonia

Aspiration pneumonia is a condition that could be difficult to diagnose due its overlap with other conditions and its inconsistent definitions. Patients suffering from this illness are usually elderly, frail, malnourished, or bedridden, and they often have multiple health conditions, including brain diseases. Aspiration pneumonia shares symptoms with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), such as cough, fever, and tiredness. This makes it challenging to tell the two illnesses apart. When doctors suspect CAP, they get a full patient history, including instances of trouble swallowing and coughing during meals, which can help diagnose aspiration pneumonia.

It’s important to note that just because a patient with pneumonia has been aspirating, it doesn’t automatically mean they have aspiration pneumonia. However, given that older adults are more prone to aspiration and pneumonia, doctors should consider aspiration pneumonia likely in these cases. They should evaluate and manage swallowing difficulties accordingly. If the patient has a history of large volume aspiration events, then aspiration pneumonitis is a stronger possibility.

Patients with aspiration pneumonia usually show signs of the condition acutely. However, it can sometimes present more slowly if the bacteria causing the pneumonia are not very aggressive. Common symptoms include shortness of breath, low oxygen levels, and fever. In aspiration pneumonitis, patients experience very sudden and severe low oxygen levels. This can lead to serious lung damage, or it may resolve completely within two days.

During the initial patient assessment, doctors consider any episodes of decreased awareness and trouble swallowing. It’s vital to check how well older adults can swallow tablets, solids, and liquids. Doctors should also ask about past cases of pneumonia and gum disease because they can suggest the presence of aspiration pneumonia. Furthermore, knowing about the patient’s lifestyle, such as smoking and alcohol consumption, helps identify risk factors for the condition.

In older patients where there is no history of aspiration, a cognitive assessment becomes a critical part of the physical examination. Immediate evaluation for low oxygen levels is also key to ensure prompt treatment.

Testing for Aspiration Pneumonia

The British Thoracic Society offers recommendations on testing for suspected aspiration pneumonia, which is when food, stomach acid, or saliva enters the lungs, potentially causing infection. These include a chest X-ray and a CT scan of the chest if the X-ray results are unclear, or if a CT scan is necessary to rule out other conditions. Tests to identify microorganisms in sputum (mucus) and blood, as well as a complete blood count, are also conducted. While these tests alone do not confirm the diagnosis, they are useful for gauging the severity of the patient’s condition and tracking their nutritional status.

To definitively diagnose aspiration, a type of swallowing study known as a videofluoroscopy is typically used. It becomes clear that aspiration has occurred if a substance called barium, used to improve X-ray imaging, is seen below the true vocal cords. It’s important to remember that aspiration can occur in episodes; one study alone might not be enough to rule it out.

Other tests for aspiration include an endoscopic examination of swallowing, which allows doctors to directly observe the swallowing process, and scintigraphy, mostly used in research. Accurate swallowing study machines are available only in specialized clinics.

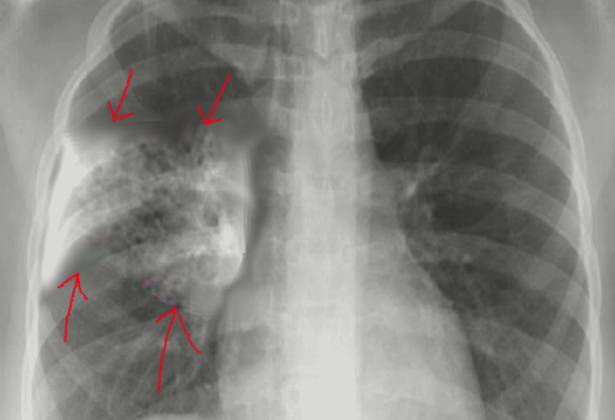

Aspiration pneumonia usually shows up as “infiltrates” or accumulations in the lungs on radiological studies. These infiltrates can appear in different parts of the lungs depending on a person’s position; standing or bedridden. Most cases affect the right lung more than the left, but both lungs can be involved, especially in patients who aspirate while standing up.

Even though a simple chest x-ray can provide this information, it may miss an infiltrate in some cases. That’s when a CT scan can help, as some studies have shown that it can catch cases that a chest x-ray misses. When the chest x-ray is unclear, an ultrasound can be used before a CT scan to detect pneumonia.

On the lab testing side, results usually show signs of inflammation and infection like a high white blood cell count. However, for frail older patients, an immune response might not be robust enough to show such signs. Currently, there is no specific test or biomarker that can definitively identify aspiration pneumonia.

An algorithm has been proposed recently to help diagnose aspiration pneumonia and distinguish it from similar conditions. According to this algorithm, diagnosing requires a combination of clinical symptoms, evidence from chest imaging, and a history of aspiration. Risk factors for aspiration include being frail, a history of stroke, stomach and mental conditions, among others. In addition, hygiene factors like poor oral health, use of antibiotics, and use of certain medications can make a person more prone to bacteria, increasing the risk of aspiration pneumonia.

This diagnosis becomes less likely if the patient doesn’t have a history of aspiration, risk factors for aspiration, or risk factors for oral bacteria, even if they show typical symptoms and evidence on the chest X-ray.

ventilator-associated aspiration pneumonia.

Treatment Options for Aspiration Pneumonia

Doctors today approach aspiration pneumonia differently than they used to. They no longer use anaerobic coverage, a way of targeting certain bacteria in the initial treatment of aspiration pneumonia. This is because these bacteria are rarely involved in this type of pneumonia and our diagnostic techniques can’t reliably detect them. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) advises doctors to use anaerobic coverage only in very specific cases.

To treat aspiration pneumonia effectively while reducing the unnecessary use of antibiotics, doctors follow the latest guidelines which include maintaining high levels of oxygen in the patient’s body with mechanic ventilation support, especially when the aspiration involved small volumes.

How severe the pneumonia is will determine the treatment plan. Severity can be determined using a list of symptoms outlined by the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and IDSA. These include breathing rates above 30 breaths per minute, certain temperature and blood pressure levels, and more.

As for the therapies that can be used, most patients with community-acquired aspiration pneumonia respond well to ampicillin/sulbactam, carbapenems, or respiratory fluoroquinolones such as levofloxacin or moxifloxacin. There are specific treatments recommended based on whether the patient has severe pneumonia and other factors such as comorbidities, risk factors for antibiotic-resistant pathogens, or recent hospitalizations.

If a patient has been in the hospital recently, received antibiotics, or has a risk of MRSA or P aeruginosa, they should be tested for these infections. If they have a history with these organisms, treatment should include coverage for them.

Pneumonia treatment usually takes a minimum of 5 days, with longer durations for patients with a slower response or more severe cases. It’s important to remember that patients with suspected aspiration pneumonia and lung abscesses or empyema might need anaerobic coverage, but the evidence supporting this practice is very weak.

Special attention should be given to clindamycin, an antibiotic that could increase the risk for Clostridium difficile colitis, a severe inflammation of the colon. Its use should be carefully considered. Finally, glucocorticoids, a type of medicine, have been investigated for aspiration pneumonia treatment, but they have not demonstrated consistent benefits.

Similar recommendations to treat aspiration pneumonia are offered by the British Thoracic Society, which also stresses the diverse bacteria related to aspiration pneumonia and the need for a wide range of antibiotics. The Society, however, encourages initial treatment with amoxicillin due to ecological concerns tied to the use of cephalosporins.

One other crucial aspect of treating aspiration pneumonia is to ensure patients get enough oxygen. The British Thoracic Society guidelines recommend an oxygen saturation level of 94% to 98% for most patients, with exceptions for those at risk for high carbon dioxide levels in their blood.

What else can Aspiration Pneumonia be?

When doctors are trying to diagnose aspiration pneumonia, there are a few other conditions that show similar symptoms. These conditions include:

- Aspiration pneumonitis

- Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- Viral pneumonia

- Negative-pressure pulmonary edema

It’s particularly important to distinguish aspiration pneumonia from these. The last condition, negative-pressure pulmonary edema, can show up in medical scans as evenly spread damage to the lungs. This can happen when a person inhales forcefully against a blocked airway – which can happen during anesthetic for surgery, an episode of choking, or a near-drowning event. This is why it’s crucial for doctors to carry out careful testing and analysis to arrive at the correct diagnosis.

What to expect with Aspiration Pneumonia

: Patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) who are likely to inhale food or liquid into their lungs (aspiration) tend to have higher death rates during their hospital stay and within 30 days of their hospital admission. This risk also increases their chances of getting pneumonia again and being re-admitted to the hospital. However, there isn’t enough data to draw precise conclusions about the relationship between aspiration pneumonia and these outcomes.

Older adults over 80 with pneumonia and those with aspiration pneumonia showed higher death rates, higher sodium levels, and reduced kidney function compared to peers of the same age but without evidence of aspiration.

In the United States, aspiration pneumonia caused an average of 58,576 deaths per year between 1999 and 2017. Most of these deaths (76%) were in people aged 75 or older. For hospitalized patients with aspiration pneumonia, the death rate is around 10% to 15%. This rate is even higher for older patients and those with head and neck cancer, at around 20%.

For patients with Parkinson’s disease, even the early stages come with a high risk of death from aspiration pneumonia. A large-scale study in South Korea found that two-thirds of patients with Parkinson’s disease died within a year of their first aspiration pneumonia episode.

The severity of aspiration pneumonia is a major factor that predicts mortality. But a patient’s nutritional status also plays a part in determining the risk of mortality in patients with aspiration pneumonia. That’s why it’s recommended to assess the nutritional status of these patients early on, to anticipate the disease’s course and work towards better clinical outcomes.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Aspiration Pneumonia

Common complications of aspiration pneumonia include lung abscesses and empyema, which are collections of pus within the lungs caused by certain types of bacteria. To reduce the risk of these complications, doctors usually start patients on antibiotics promptly. The choice of antibiotic is often based on the risk of the patient having infections that are resistant to certain drugs.

Patients with aspiration pneumonia also run the risk of becoming malnourished and dehydrated. These risks are not only connected to the predisposing conditions that led to the pneumonia, but also to the dietary changes that may be required as part of the patient’s treatment. For instance, patients may be put on diets that include thickened liquids, which they might avoid due to their consistency, leading to reduced food and fluid intake. In fact, some people can end up consuming as little as 22% of the recommended daily amount of food and drink. Therefore, thorough monitoring and follow-ups are necessary to ensure that these patients are keeping themselves adequately nourished and hydrated.

Furthermore, recurrent hospital visits and lower quality of life are common among elderly individuals and those with weakness who have had aspiration pneumonia. People with swallowing difficulties are notably at higher risk of being readmitted to the hospital for pneumonia, with a rate of 6.7 per 100 person-years compared to 3.67 per 100 person-years for those without swallowing problems or history of inhaling foreign substances into their lungs. A team of health professionals including nutritionists, speech therapists, physiotherapists, and nurses play a crucial role in helping improve the quality of life for these individuals and reducing their chance of needing to return to the hospital.

Preventing Aspiration Pneumonia

Regular check-ups and tests are crucial for spotting and managing problems with swallowing. This approach can help prevent a type of lung infection known as aspiration pneumonia and improve patient health. European health organizations recommend all stroke patients be checked for dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing, to diagnose it early, prevent pneumonia after a stroke, and reduce early death risk.

This approach is just as essential for patients with Parkinson’s disease. Early check-ups and continuous assessments help for timely treatments and lower the chances of complications relating to aspiration, or inhaling food or liquid into the lungs.

To prevent aspiration pneumonia, a teamwork approach is best. Speech therapists and dietitians work to restore normal swallowing and coughing. Nurses and dental hygienists focus on reducing harmful bacteria in the mouth, while nutritionists ensure patients are staying hydrated and well fed, especially when they have been prescribed food and drinks with modified consistencies.

Patients at risk of inhaling food or liquids into their lungs should be evaluated before it happens. Nurses play a key role in identifying patients at high risk. There are many tools available to help identify this risk, including simple questions that can be asked, such as: “Do you cough and choke when you eat and drink?”, “Does it take longer to eat meals than it used to?”, “Have you changed the type of food you eat?”, and “Does your voice change after eating or drinking?”. An affirmative answer to any question indicates an issue with swallowing.

If a patient is found to be at risk of aspiration, various strategies can help to prevent aspiration pneumonia. These include techniques like tucking the chin to the chest while swallowing, which provides physical support to the throat muscles, or medication that preserves coughing to reduce the risk. There can also be benefit in exercises that strengthen the breathing muscles and vocal exercises for individuals with voice closure issues.

Oral care routines have been shown to reduce the frequency and fatalities due to aspiration pneumonia. Non-foaming fluoride toothpaste is recommended for patients at risk. Additionally, changing the thickness of fluids and texture of food can help reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonia although the evidence supporting this is small.

However, modified diets can come with negative side effects. They might increase the risk of malnutrition, dehydration, and urinary tract infections, especially among elderly patients with underlying neurological conditions. So, utmost care and monitoring are required to avoid these risks. Smaller food portions are advised to reduce residue and subsequent aspiration events. Balancing proper nutrition while minimizing the risk of aspiration is very important. Guidelines suggest tube feeding for patients who have not eaten for more than 3 days or if less than 50% of nutritional requirement is met for more than 10 days.