What is Chronic Emphysema?

Pulmonary emphysema is a medical condition where the small airways in the lungs (known as respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and alveolar sacs) enlarge permanently due to the destruction of their walls. This destruction doesn’t cause any scarring changes, often termed as fibrotic. Emphysema disrupts the basic units of ventilation in the lungs, hindering the exchange of gases.

Functionally, it results in a breathing issue where airflow is obstructed, which can be seen in the lung function test known as spirometry. Emphysema is a part of a group of diseases called chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD. When emphysema advances, it’s a common and severe cause of long-term respiratory failure and sudden severe symptoms that can be life-threatening.

Recognizing and managing emphysema in its early stages is critical due to its high rates of illness and death. It differs from a lung disease called interstitial pneumonia because it doesn’t cause fibrosis, or scarring of the lung tissue. However, there are cases where patients with proven emphysema also have lung fibrosis, a condition known as combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE).

Repeated severe instances of emphysema and consequent extreme symptoms can cause a faster than expected reduction in lung function with age.

What Causes Chronic Emphysema?

Emphysema, a severe lung condition, is strongly linked to cigarette smoking. It’s estimated that about 10 to 15% of smokers get emphysema during their lives, and the likelihood increases with the amount and length of smoking. However, various factors are speculated to cause emphysema, including genetic factors.

One genetic factor is the deficiency of a substance called alpha-1 anti-trypsin (AAT). This genetic disease can cause emphysema, particularly in younger people, and it tends to affect the lower part of the lungs. On the other hand, emphysema from smoking usually starts to appear around the age of 50 and above, primarily affecting the upper part of the lungs. There’s often a history of at least 20 years of heavy smoking involved.

Environmental and occupational exposures also play a part in causing emphysema. This includes exposure to specific chemicals, secondhand smoke, or work-related substances. Frequent lung infections can also lead to the development of this condition.

In the past, in developing countries, exposure to smoke from traditional wood-burning stoves used for cooking was a common cause of emphysema. There have also been reported cases of emphysema in young people thought to be linked to marijuana smoking.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Chronic Emphysema

Emphysema, also known as Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) which includes chronic bronchitis, impacts a large number of people globally. Specifically, it touches nearly 250 million individuals worldwide. In the United States, this disease affects around 14 million people. The number of COPD cases has been slowly rising, largely due to an increase in smoking. COPD is also more common in areas with high levels of environmental pollution. Even non-smokers can develop emphysema, an example being coal workers’ pneumoconiosis. Generally, more men than women have emphysema, and smoking plays a significant role in this.

- Emphysema, or COPD, is a widespread condition affecting around 250 million people globally.

- In the United States, about 14 million people are affected by this disease.

- The number of COPD cases is slowly increasing, mainly due to the increase in smoking.

- Municipalities with higher environmental pollution have a greater prevalence of COPD.

- Non-smokers can also develop emphysema, such as in the case of coal workers’ pneumoconiosis.

- Prevalence of the disease is slightly higher in males than females, and this can be attributed to the degree of smoking.

Signs and Symptoms of Chronic Emphysema

Emphysema is a condition usually affecting those in their 50s and older who have a history of smoking extensively. These individuals often have a long-term, productive cough and increasing difficulties with breathing. Over time, these symptoms worsen and can interfere with daily activities. There may also be unplanned weight loss, leading to a thin, weak physical appearance. In severe flare-ups, patients may cough up large amounts of phlegm, develop extensive wheezing, and progress towards increased carbon dioxide in the blood with related low oxygen levels leading to breathing failure.

Typically, people suffering from this condition may display ‘purse lip breathing’, breathe rapidly, and use additional respiratory muscles. Upon listening to the lungs, the doctor might hear reduced airflow. Complications from long-term emphysema may also lead to symptoms and signs of heart failure on the right side of the heart. These patients are often described as ‘pink puffers’ as they have a red complexion and an expanded chest due to their lungs overfilling with air. These individuals usually do not show signs of cyanosis (blue skin and lips) in the early stages. In contrast, patients suffering chronic bronchitis issue, often appear cyanotic and are referred to as ‘blue bloaters’. Spitting up blood is uncommon in COPD, but if it is seen, more serious conditions including cancer should be considered, based on other symptoms and the patient’s medical background.

It is worth noting that there is a condition called Asthma COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS) where both these conditions co-exist. Asthma is generally known to have triggers leading to flare-ups and can show seasonal changes. It is important to note other upper airway conditions like chronic sinus inflammation may also be present so a detailed history should be taken.

Family history is essential because of a condition known as AAT deficiency which can be inherited. Often, habits like smoking may be common in the family. Also, it’s beneficial to know about any recent exposures to sick individuals as viral infections are the most common cause of bringing on symptoms of COPD. A history of vaccinations like the annual flu shot is also important to note.

Testing for Chronic Emphysema

If you’ve been experiencing symptoms that your doctor believes could be related to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), they might conduct a variety of tests to confirm the diagnosis. These tests all measure your lung function in different ways.

One key test is a Pulmonary Function Test (PFT) which includes: spirometry, a test that measures how much air you can breathe in and out as well as the speed of your breath; bronchodilator reversibility testing, which can show if your airways improve after taking a bronchodilator drug; lung volumes, which measure the total amount of air in your lungs; measuring carbon monoxide diffusion capacity, which shows how well the gas is moving from your lungs into your blood; and a flow volume loop which can reveal any blockages or restrictions in your airways.

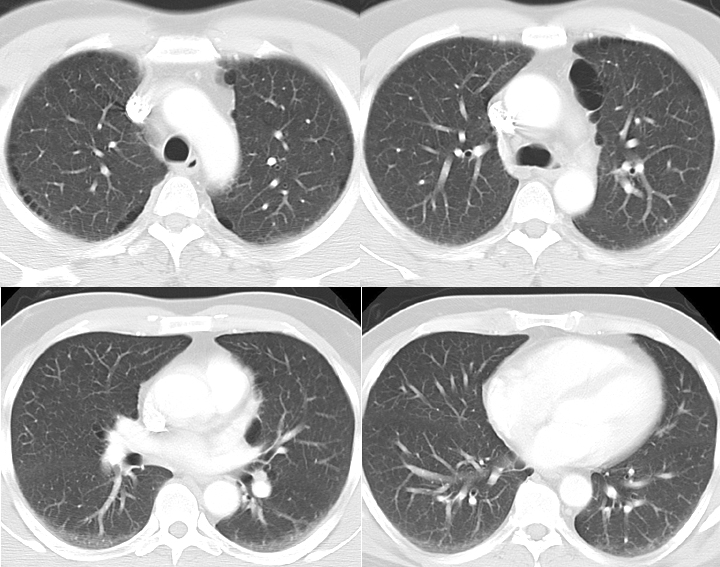

Other diagnostic tools that doctors may use include arterial blood gas tests, which measure how much oxygen and carbon dioxide is in your blood; Chest X-rays, which can reveal signs of emphysema or other lung diseases; CT scans, which can provide a more detailed image of your lungs; and an echocardiogram, to check whether your heart is contributing to your symptoms.

In some cases, especially in young patients, the doctor may also order genetic testing for Alpha-1 Antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency, a condition that may lead to lung problems. Additional investigations might be needed if there’s suspicion of other coexisting conditions like asthma or pulmonary fibrosis.

Your doctor might also ask you to do a 6-minute walking test while your oxygen levels are being measured to determine if you need long-term oxygen treatment.

Based on the results of your tests, your doctor can determine the severity of your condition using a system established by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Diseases (GOLD). The system categorize COPD into four groups from Mild (Group A) to Very severe (Group D), based on the level of your symptoms and how often you have flare-ups.

Treatment Options for Chronic Emphysema

Treatment for this condition includes both medicine and other non-drug approaches. Key actions to slow down further damage to the lungs are to quit smoking and avoid exposure to environmental pollutants. It’s essential that patients get the annual flu shot and suitable pneumonia vaccinations, unless there is a reason they shouldn’t. Avoiding getting too close to people who are visibly unwell can also help to prevent worsening of the condition. Proper nutrition plays an important role as well. Having a nutritionist assist with meal planning may be beneficial.

If at rest or during exertion, a patient’s oxygen levels drop below certain levels, they may need to use oxygen therapy regularly. Engaging in pulmonary rehabilitation, a program designed to improve lung function and physical stamina, has shown to be effective. Regularly monitoring how well the lungs are working is also recommended, as it can help detect if the condition is getting worse more quickly.

The main treatment for this condition is medication. This includes inhaled medicines like albuterol and levalbuterol, types of drugs known as anticholinergics (like ipratropium), inhaled steroids, and drugs called long-acting beta agonists (LABA) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA). Traditionally, a combination of inhaled steroids and LABA was more commonly used; however, because of concerns about increasing rates of pneumonia among these patients, some doctors are now opting to combine LABA and LAMA instead. It’s important to note that using LABA alone, without steroids or LAMA, has resulted in increased deaths when used for treating asthma. For advanced cases, doctors might suggest triple therapy, which combines inhaled steroids, LABA, and LAMA. Many of these drugs can also be delivered in a mist that the patient breathes in, which can be useful for those who have trouble using inhalers. If the condition still does not improve, other medication options might be considered such as roflumilast (which helps lessen the chance of severe episodes), theophylline, long-term antibiotics like azithromycin, and, as a last resort, long-term oral steroids (although these are not commonly recommended).

Systemic steroids, which are taken by mouth or by injection, are mainly used to treat sudden worsening (exacerbations) of the condition in conjunction with inhaled medicines. Methylprednisolone, hydrocortisone, dexamethasone, and oral prednisone are some of the most commonly used steroids.

For patients who have a deficiency in a protein known as alpha-1 anti-trypsin, they may be given additional copies of the enzyme in a treatment known as “augmentation therapy”.

In some specific cases, surgery might be possible to reduce the volume of the lungs. In severe cases, known as “end-stage” disease, a lung transplant could be another option, but only for suitable patients.

What else can Chronic Emphysema be?

When a doctor is trying to diagnose Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), they need to consider a wide range of other possible health issues because the symptoms of COPD are common to many conditions. For example, bronchial asthma can cause blockages in airflow, similar to COPD. It should also be noted that long-term asthma can cause airflow obstruction, even if the person doesn’t have COPD.

Other lung or heart-related conditions, including pulmonary fibrosis, bronchiectasis, heart failure, high blood pressure in the lungs, or illnesses related to the blood vessels in the lungs, may share some symptoms with COPD. In addition, infectious diseases like pneumonia and tuberculosis, fungal infections, and inflammatory conditions like interstitial pneumonia can all cause a chronic cough, which is a common symptom of COPD.

If the patient is elderly or suffering from a neurological disease, chronic aspiration (which means habitual inhalation of food particles or fluids into the lungs) should be considered in diagnosis treatment options. Also, diseases outside the lungs, like severe acid reflux or ongoing inflammation of the sinus or nasal passages, should be considered under the right conditions while making a diagnosis.

What to expect with Chronic Emphysema

Emphysema is a serious lung disease that permanently destroys the walls of the small air sacs in your lungs. However, if caught early and treated properly, it’s possible to slow the progression of this disease. The most important step in preventing further lung damage is to stop smoking. Other factors that can make emphysema worse include poor nutrition, a overactive airways, being male, bacterial infection, a weakened immune system, and having heart or other lung diseases.

Doctors often use a tool called the BODE index, which looks at your body mass, lung obstruction level, shortness of breath, and exercise capacity, to predict how likely someone might die from emphysema. If someone with emphysema frequently has high levels of carbon dioxide in their blood, it’s a sign the disease has been around for a long time and their outlook isn’t good. Each flare-up of symptoms can lead to a larger than normal drop in lung function.

If scans of the chest show emphysema, this also suggests a worse outlook. However, quitting smoking and using long-term supplemental oxygen can help reduce the chance of death from this disease.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Chronic Emphysema

Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) can experience severe breathing complications, which can become life-threatening if left untreated. Even if the disease is managed properly, these individuals may need supplemental oxygen at home. Continuing to smoke can increase their risk of developing cancer.

Furthermore, COPD can give rise to a variety of complications and symptoms such as:

- Reduced ability to exercise

- Significant weight loss and muscle wasting

- Heart complications (known as cor pulmonale)

- Frequent chest infections

Patients may also often face psychological challenges including:

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Irritability

Physicians treating these patients must be ready to address these issues as part of the overall treatment approach.