What is Pleural Effusion?

A pleural effusion is a medical condition where there is too much fluid in the space surrounding the lungs, called the pleural space. Generally, a small amount of liquid is naturally present in this space to allow the lungs to move smoothly while breathing in and out. However, certain diseases can cause an imbalance, making this space fill up with excess fluid. This condition affects an estimated 1.5 million patients each year, and is generally seen as a sign of increased health risk and illness in certain groups.

To diagnose a pleural effusion, doctors will assess a patient’s symptoms, do imaging tests, like an X-ray, and may take a sample of the fluid from the space, known as a pleural fluid analysis. A procedure called thoracentesis may be carried out to both diagnose and treat this condition. Treatment strategies focus on addressing the root cause of the effusion, draining the surplus fluid, and managing any complications such as infection or thickening of the pleural space.

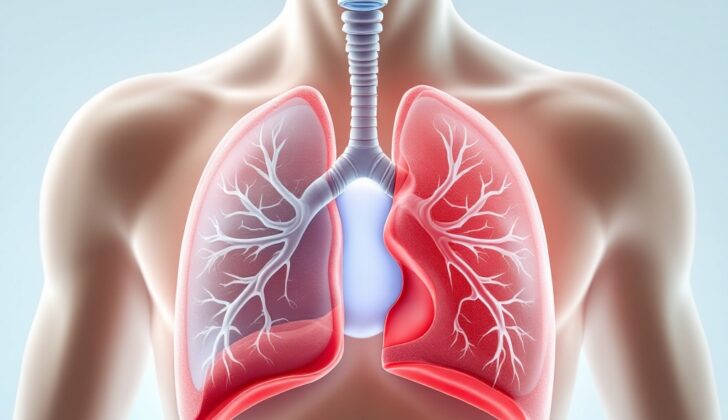

Now, to briefly describe the anatomy of the pleural space: it’s located right within the chest and houses the lungs, which expand and contract while breathing. The pleural space is between two protective membrane layers called the visceral and parietal pleura, and usually contains a thin layer of fluid that helps the lungs move smoothly during breathing.

The visceral pleura is the inner layer that directly covers and follows the shape of the lungs, helping them to function smoothly during breathing. The parietal pleura is the outer layer, which lines the inside of the chest and is segmented into different portions – mediastinal, diaphragmatic, costal, and cervical. This outer layer is thicker and has more blood supply than the inner layer and also contains nerve endings responsible for the sensation of pain, which is why you may feel pain during certain medical conditions.

The visceral and parietal pleura create the pleural cavity which typically contains a small amount of fluid to reduce friction. Physical factors like gravity and breathing, along with certain pressures, help maintain this delicate fluid balance.

Conditions like pleural effusion or pleurisy, which cause inflammation of the pleura, can disturb these functions and result in breathing problems and complications. Therefore, a deep understanding of the structure and function of the pleural space is key to effectively diagnosing and treating the diseases related to it.

What Causes Pleural Effusion?

Pleural effusion is a condition where too much fluid builds up between the layers of tissue that line your lungs and chest cavity. This fluid can be categorized into two types – transudate or exudate – according to a method called Light’s criteria. Determining which type of fluid has built up is important to understand what’s causing the condition and to plan further testing. Light’s criteria looks at both the ratio of fluid protein to blood protein levels and fluid LDH (a type of enzyme) to blood LDH levels.

The fluid is identified as exudative if one or more of these are true:

* The amount of protein in the fluid is more than half of what it is in the blood.

* The amount of LDH in the fluid is more than 60% of what it is in the blood.

* The amount of LDH in the fluid is more than two-thirds of the highest normal amount in the blood.

If none of these conditions are met, the fluid is considered transudative.

Transudative pleural effusion can be caused by conditions that change the pressures in the pleural space (area between the lungs and chest wall), such as congestive heart failure, nephrotic syndrome (a kidney disorder), liver cirrhosis (liver damage), low levels of albumin (a type of protein), or from peritoneal dialysis (a treatment for kidney failure).

Exudative pleural effusion is often caused by lung infections like pneumonia or tuberculosis, cancer, inflammatory conditions like pancreatitis, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, injury to the heart, accumulation of lymph fluid in the pleural space (chylothorax), blood in the pleural space (hemothorax), post-heart bypass surgery, and non-cancerous asbestos-related condition.

Fewer common causes include blood clot in the lung (pulmonary embolism), reactions to medications, radiotherapy, rupture of the esophagus, and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (a complication from fertility treatment). Certain medications such as methotrexate, amiodarone, phenytoin, and dasatinib can also cause pleural effusion.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Pleural Effusion

Pleural effusion, a condition affecting the space around the lungs, is the most common type of lung-related disease. It impacts about 1.5 million people in the United States each year. However, because more large-scale studies are needed, we don’t fully understand all the possible causes. The rate at which it occurs seems to differ by location. Conditions like heart failure, malignant pleural effusion (a cancer-related condition), and parapneumonic effusions (related to pneumonia) are the most common reasons for this condition each year.

Signs and Symptoms of Pleural Effusion

A pleural effusion refers to the build-up of fluid between the layers of the tissue that lines the lungs and the chest cavity. Depending on how much it affects the expansion of the lungs, symptoms can range from none at all to shortness of breath during exertion. Despite extensive research, the specific cause of this breathlessness is still unclear. The amount of fluid does not always correspond to the severity of the symptoms. It seems that the fluid’s effect on lung expansion plays a much larger role. Other potential causes include decreased oxygen and existing lung diseases, such as fluid buildup in the lungs due to heart failure.

Individuals may experience a cough, fever, and general feelings of discomfort or illness, dependant on what caused the effusion. In rare cases, the sheer volume of the effusion can impact heart function and create a condition similar to tamponade, a serious condition where fluid compresses the heart. When the tissue lining the lungs, known as the pleura, is inflamed—an issue called ‘pleurisy’—people often report sharp, intense, pain that progresses and regresses in waves with their breathing or coughing. If pleuritic pain lessens, it may signify the development of an effusion. Persistent pain may also indicate serious conditions such as mesothelioma.

Diagnosis can vary. In the case of a large effusion, healthcare professionals may notice a fullness between the ribs and a dullness when they tap on the chest. Listening to the chest might reveal muffled breath sounds and a change in the normal sounds heard when a patient speaks. A sound referred to as a ‘pleural rub’, often confused with coarse crackles, can be heard during active pleurisy without any effusion.

Since a pleural effusion can result from various diseases, doctors need to look at the potential causes. They will take a full medical history, focusing on any underlying lung conditions, other health problems, medications, signs of infectious diseases, and any factors that might predispose an individual to cancer. They will also conduct a comprehensive physical examination to assess different potential diagnoses.

- For example, they may suspect heart failure if the patient has distended neck veins, a certain heart sound (S3), and swelling in the legs.

- Advanced liver disease could be a consideration for someone with fluid build-up in the abdomen (ascites) and a network of dilated veins around the umbilicus (caput medusae).

Testing for Pleural Effusion

A chest X-ray is the first step doctors usually take to identify accumulation of fluid in the lungs, also known as pleural effusion. If a certain curve, called the meniscus sign, is present, it means there’s probably more than 200 milliliters of fluid in the lungs. But a side view X-ray can even detect as little as 50 milliliters of fluid.

Ultrasound is another commonly used and efficient method to determine and confirm the presence of fluid in the lungs and to plan a procedure to remove the fluid, known as a thoracentesis.

If you ever experience pleural effusion, your doctor will need to analyze the fluid to figure out the cause. This can usually be done with a thoracentesis, unless they suspect the cause is heart failure. In that case, they may try to treat it with diuretics (medications to help reduce fluid in the body) first. Ultrasound will also be crucial to prepare for this procedure. It provides valuable information about the fluid, which can help in figuring out the cause.

Various characteristics of the fluid can indicate different conditions. For instance, the presence of odd structures within the fluid, like septations, might suggest that the effusion is more complicated and could be due to lung infection or a collection of pus in the pleural space. If the fluid appears smoky on the ultrasound, that could be a sign of hemothorax, which is accumulation of blood in the pleural space, and it might require a chest tube to remove the fluid.

Once the fluid is removed, it will be sent for testing. Doctors will be looking at a range of markers, including pH, levels of protein and LDH, glucose levels, cell count, and results of the gram stain and culture. These results can then be used to determine if the fluid is an exudate (fluid with a high content of protein and cells, suggesting injury or inflammation) or transudate (fluid with low protein and cells, typically due to imbalance between creation and removal of fluid).

If the fluid is identified as exudate, more tests will be performed to identify the cause. For instance, looking at the type of cells present might narrow down the diagnosis. If there are mostly lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell), it might suggest tuberculosis, yellow nail syndrome, or cancer, among other things. If there are a lot of neutrophils (another type of white blood cell), it might indicate a lung infection. If the pH is below 7.2, it might suggest a complex pleural effusion from pneumonia which may almost always require drainage, esophageal rupture or rheumatoid arthritis.

In specific situations, additional markers will be tested for, such as acid-fast bacilli smear for suspected tuberculosis, or amylase levels for pancreatitis. If the pleural fluid appears milk-white, it might be indicative of chylothorax (lymphatic fluid in the pleural space), which can be confirmed by high levels of triglycerides.

For suspected cases of malignant pleural effusion (cancerous fluid), cytology tests will be performed. If fluid testing doesn’t yield clear results, more invasive procedures like a needle biopsy with imaging guidance or thoracoscopy (a procedure allowing doctors to view the chest cavity with a small camera) may be necessary. For transudative effusion (often caused by heart failure), just the clinical presentation might be enough for diagnosis, and additional tests are generally not needed.

Treatment Options for Pleural Effusion

The main goal in managing the buildup of fluid between layers of the tissue that lines the lungs and chest cavity, known as a pleural effusion, is to identify and manage the underlying cause. Draining the fluid can help to relieve symptoms in patients who are struggling with breathlessness or discomfort.

If patients aren’t noticeably experiencing symptoms, fluid drainage is usually only done to determine the cause of the effusion. Drainage might also be performed if there are signs of infection or heavy bleeding. With conditions like heart failure, a procedure called thoracentesis (drainage using a needle) is only recommended if other medications like diuretics don’t work or if the patient is suffering from severe symptoms. Chylous effusions, which involve a specific type of fluid called chyle, are typically managed without invasive treatments, though some might need surgery.

Thoracentesis can be both a diagnostic technique to discover the reason for the effusion and a therapeutic (treatment) procedure. Here are some key considerations for this procedure:

- Using an ultrasound (an imaging method using sound waves) during the procedure can make it more successful and lessen the risk of a collapsed lung (pneumothorax).

- Ultrasound can help see if fluid is trapped (sequestrations).

- Once the fluid is drawn out, laboratory tests checking for substances and cells can help identify conditions behind the effusion.

- Light’s criteria, a set of measures to find out the type of the effusion, is used.

- An effusion with a high number of white blood cells called lymphocytes may indicate cancer or tuberculosis.

- The pH level of the fluid is checked. pH is a measure of how acidic or basic the fluid is.

- Effusions linked with cancer can be identified in about 40% to 60% of samples.

In cases where the effusion is caused by a complicated pneumonia or an empyema (pus within the chest), a tube is inserted into the chest to drain the fluid, combined with antibiotics to clear any infection. Small tubes can be just as effective as larger ones, and they’re often easier to place and less painful for patients.

Additional treatments can also be used to improve the drainage. However, in some cases, a surgical procedure called thoracoscopic decortication (removal of the outer layer of tissue) may be necessary.

Those diagnosed with effusion caused by cancer typically don’t need repeated fluid drainage unless there’s an infection or severe symptoms. If patients need frequent drainage, they may consider options like pleurodesis or tunneled catheter placement which are procedures to prevent fluid buildup. It’s important to note that no more than 1.5 liters of fluid should be drained in a single session to prevent a condition known as reexpansion pulmonary edema, which is fluid buildup in the lungs causing shortness of breath.

What else can Pleural Effusion be?

When dealing with a medical condition called pleural effusion, which relates to a buildup of fluid in the lungs, doctors keep in mind a few other conditions that might seem similar but are different. These can include:

- Diaphragmatic paralysis: This can seem like pleural effusion on x-rays because it appears as a dense, cloud-like substance. Typical signs of diaphragmatic paralysis, though, include an unusual elevation of the diaphragm muscle in the chest, along with a smooth surface and a thin edge where the ribs and diaphragm meet.

- Lobar pneumonia: This lung infection can also look like an effusion on conventional x-rays due to its uniformly cloudy appearance. However, using an ultrasound scan can help tell the two conditions apart.

- Lobar collapse: If a section of the lung collapses and loses its volume, the x-ray may look uniformly cloudy, similar to an effusion.

To distinguish pleural effusion from these conditions, a thorough health check-up, together with the right medical imaging and lab tests, is necessary.

What to expect with Pleural Effusion

There isn’t a lot of information available about the factors that predict the outcome of a condition called pleural effusion, which is when fluid collects in the space around your lungs. We do know that people with a type of this condition, where the fluid is due to cancer (malignant effusions), typically have a poor outcome.

However, the death rate for those with non-cancerous (nonmalignant) effusions hasn’t been studied very much. Yet, several future-looking (prospective) studies have suggested that having an effusion might be a possible sign of a higher chance of dying.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Pleural Effusion

: Pleural effusion, a condition where excess fluid builds up around the lungs, can cause a variety of health problems. One such problem is empyema, which is when infected fluid accumulates in the space around the lungs. This could potentially lead to a serious, body-wide infection called sepsis, or issues with breathing. To treat empyema, doctors will often use powerful antibiotics and possibly remove the fluid in severe cases using methods like thoracentesis or inserting a chest tube.

Pleural effusion may also lead to a build-up of thick, fibrous tissue around the lungs due to chronic inflammation or repeated instances of pleural effusion. This thickening can result in less room for the lungs to expand, causing difficulties with breathing and can even lead to a condition called restrictive lung disease. Mild cases might improve with exercises to strengthen the lungs or steroid medications. However, in severe cases, surgeries like thoracoscopy or open decortication may be needed to remove the fibrous tissue, which will enable the lungs to expand better and improve breathing.

In shorter terms, the potential complications are:

- Empyema (accumulation of infected fluid around the lungs)

- Systemic infection or sepsis

- Respiratory compromise or difficulties in breathing

- Pleural thickening (build-up of fibrous tissue around the lungs due to inflammation or repeated instances of fluid build-up)

- Decreased lung expansion

- Impaired respiratory function

- Restrictive lung disease

Preventing Pleural Effusion

To prevent the onset of a condition called pleural effusion, which is the build-up of excess fluid between the tissues lining the lungs and chest, there are a few simple lifestyle changes one can take. These include regular exercise, eating a healthy diet, cutting down on alcohol, and stopping smoking. Getting vaccinated against diseases like pneumonia and the flu can also help since these respiratory infections could lead to pleural effusion. If your work exposes you to harmful materials, wearing appropriate respiratory protectors can reduce the risk of this condition due to work-induced lung diseases.

Next, a secondary form of prevention focuses on spotting the signs early to stop complications related to pleural effusion. Regular health check-ups, especially for people at risk like those with heart or lung issues, can lead to the early discovery of symptoms hinting at pleural effusion. Doctors might suggest diagnostic tests such as chest x-rays and CT scans if you show signs of respiratory troubles or if you’re at high risk. If you treat medical conditions like heart failure or pneumonia promptly, they can stop these conditions from leading to pleural effusion. The correct handling of existing pleural effusions, including draining the fluids and dealing with the root causes, can stop further issues such as an infection or the return of the condition.