What is Pneumothorax?

A pneumothorax, or collapsed lung, happens when air gets trapped in the space between the lung and the chest wall. This trapped air can put pressure on the lung, causing it to collapse. Just how much the lung collapses can vary and this affects how serious the symptoms are.

The air can get into this space in two ways: either through injury or a tear in the chest wall or a tear in the lung itself. Based on this, pneumothorax is generally categorized into two types: traumatic and atraumatic.

Traumatic pneumothorax is caused by a blunt or sharp injury to the chest. Atraumatic pneumothorax, on the other hand, is further split into primary and secondary subtypes. Primary atraumatic pneumothorax occurs spontaneously without a known cause or event, while secondary atraumatic pneumothorax happens as a result of an existing lung disease.

Pneumothorax can also be classified as simple, tension, or open depending on the symptoms and severity. A simple pneumothorax does not shift the structures in the chest, unlike tension pneumothorax which is more severe. Open pneumothorax, on the other hand, is when there is an open wound in the chest causing air to move in and out.

What Causes Pneumothorax?

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax (a condition where air gets into the space between the lung and chest wall, making it difficult to breathe) can be influenced by certain risk factors. These include smoking, being tall and thin, pregnancy, having Marfan syndrome (a genetic disorder that affects the body’s connective tissue), and a family history of pneumothorax.

People with certain diseases are more likely to get secondary spontaneous pneumothorax. These diseases include COPD (a type of obstructive lung disease), asthma, HIV with a specific type of pneumonia, tuberculous infection, sarcoidosis (a disease that results in lumps or nodules in various organs, particularly the lungs), cystic fibrosis, lung cancer, certain lung scarring diseases, severe ARDS (acute respiratory distress syndrome), certain kinds of histiocytosis (a group of diseases that involve abnormal cells), Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (a rare lung disease that commonly affects women), collagen vascular disease, and the use of inhaled drugs like cocaine or marijuana. Another condition associated with secondary spontaneous pneumothorax is thoracic endometriosis, which is when tissue similar to the lining of the uterus starts growing outside the uterus.

Iatrogenic pneumothorax (caused by medical procedures) often happens after procedures like a biopsy of the pleura (tissue that lines the outside of the lungs and the inside of the chest cavity), a biopsy of a lung or of a lung nodule using a tube called a bronchoscope, inserting a central venous catheter (a tube that is placed into a large vein), performing a tracheostomy (a surgical hole in the neck leading to the windpipe), providing an intercostal nerve block (an injection to reduce pain), or using positive pressure ventilation (a way to help a patient breathe).

Mediastinum, the central compartment of the chest containing the heart, can also get filled with air due to conditions like asthma, childbirth, severe vomiting, severe cough, or trauma to the mouth or esophagus. This condition is known as pneumomediastinum.

Additionally, traumatic pneumothorax can be caused by an injury to the chest, like a rib fracture or a blow to the chest, or by participating in activities like diving or flying.

Penetrating or blunt trauma or receiving positive pressure ventilation can cause tension pneumothorax, a serious condition where air accumulates in the chest under pressure, compressing the lungs and decreasing the amount of blood, potentially life-threatening without prompt treatment. Similarly, converting a spontaneous pneumothorax into a tension one or having an open pneumothorax that works like a one-way valve can also lead to tension pneumothorax.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Pneumothorax

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax usually occurs in individuals aged between 20 and 30. In the United States, it affects 7 out of every 100,000 men and 1 out of every 100,000 women per year. There is a high risk of recurrence within the first year, ranging from 25% to 50%, with the highest chance within the first 30 days.

Secondary spontaneous pneumothorax, on the other hand, is more common in older patients, specifically those aged 60 to 65 years. For every 100,000 patients, there are about 6.3 cases in men and 2 in women, hence a male-to-female ratio of 3:1. People with COPD have a higher incident rate at 26 pneumothoraces per 100,000 patients. It’s also important to note that heavy smokers are 102 times more likely to develop a spontaneous pneumothorax than those who do not smoke.

- The top cause of iatrogenic pneumothorax is transthoracic needle aspiration (usually for biopsies).

- The second leading cause is central venous catheterization.

- These two causes are more frequent than spontaneous pneumothorax, and the incidences rise as intensive care advances.

- In hospitals, there are about 5 iatrogenic pneumothorax cases per 10,000 admissions.

It’s hard to pin down the exact incidence of tension pneumothorax. This is because about one third of patients in trauma centers have undergone decompressive needle thoracostomies even before reaching the hospital, and not all of them had tension pneumothorax.

As for pneumomediastinum, it occurs in about 1 out of every 10,000 hospital admissions.

Signs and Symptoms of Pneumothorax

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax is a condition that typically doesn’t cause severe symptoms because healthy individuals can usually handle its physiologic impact quite well. The most frequent symptoms are chest pain and shortness of breath. The chest pain can be described as a sharp, intense pain that radiates to the shoulder on the same side. In secondary spontaneous pneumothorax (SSP), shortness of breath can be more severe due to a decrease in underlying lung function.

A history of pneumothorax is important to note because recurrences can happen in 15-40% of cases, even on the opposite side.

During a physical exam, the following signs might be observed:

- Discomfort when breathing

- Increased speed of breathing

- Uneven expansion of the lungs

- Reduced vibration sensation when touching the chest

- Overly resonant sound when the chest is tapped

- Reduced or absent sounds of breathing

In a severe form of pneumothorax called tension pneumothorax, additional symptoms could include:

- Rapid heartbeat above 134 beats per minute

- Low blood pressure

- Swelling in the neck veins

- Blue coloration of the skin due to lack of oxygen

- Difficulty breathing

- Cardiac arrest

Some cases of pneumothorax that occur due to trauma may also be associated with subcutaneous emphysema, which is when air gets into tissues under the skin. It can be challenging to diagnose pneumothorax from a physical exam alone, especially in a noisy environment like a trauma bay. However, it is critical to diagnose tension pneumothorax during a physical examination.

Testing for Pneumothorax

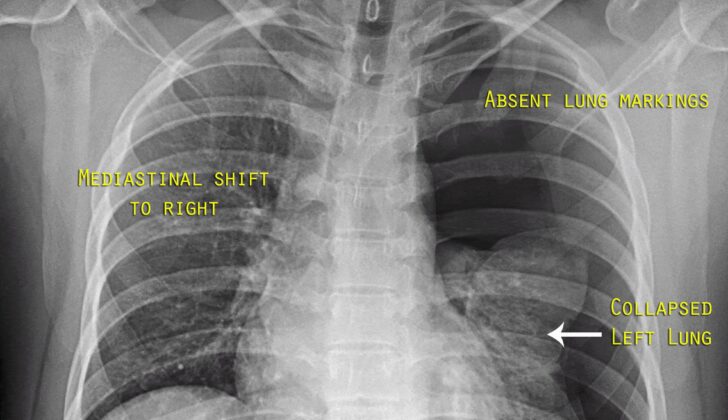

If a doctor suspects that a patient has a pneumothorax (also known as a collapsed lung), they may use several imaging methods to diagnose it. These could include a chest x-ray, an ultrasound, or a computed tomography (CT) scan. However, a chest x-ray is the most common method used for this purpose. On an x-ray, if they see a pocket of air (known as an air space) that is 2.5 cm, it’s generally equivalent to a 30% pneumothorax.

Occasionally, a pneumothorax won’t show any symptoms and so is called an “occult” pneumothorax. These can be diagnosed through a CT scan, but usually, they’re not of major concern.

Another method used in recent years is the extended focused abdominal sonography for trauma (E-FAST) exam. This exam can help diagnose a pneumothorax based on different signs in the ultrasound. The signs include the absence of “lung sliding” (which is movement of the lung within the chest cavity), the absence of artifacts called “comet tails,” and the presence of a “lung point.” However, the effectiveness of this test can vary because it heavily relies on the experience and skill of the person performing the ultrasound. Nevertheless, when done correctly, an ultrasound can have up to a 94% sensitivity and 100% specificity, making it even better than a chest x-ray.

If there’s a strong suspicion that a patient has a severe form of pneumothorax (called tension pneumothorax) and the patient’s condition is rapidly worsening, the doctor may not wait for imaging results before starting treatment. In such cases, a procedure called needle decompression could be done immediately based on the patient’s symptoms and physical examination.

Treatment Options for Pneumothorax

In cases where someone is showing symptoms of pneumothorax (a collapsed lung) and may not be stable, the first line of treatment is typically needle decompression. This procedure involves inserting a needle into the chest cavity to allow trapped air to escape. After this procedure or in cases where the pneumothorax isn’t immediately threatening, a thoracostomy tube may be inserted. This tube is placed into the chest cavity to help drain air and fluids.

Open chest wounds may initially be treated by covering them with a dressing that is left open on one side to let air escape. Further treatment of these wounds may involve inserting a thoracostomy tube and surgical repair of the chest wall.

If a person has a small, spontaneous pneumothorax (not caused by injury) and isn’t showing symptoms, they may be discharged from hospital and scheduled for a follow-up visit in 2-4 weeks. If the pneumothorax is causing symptoms or is larger, a needle may be used to aspirate the trapped air. If the patient feels better after this and the size of the pneumothorax has reduced, they might be discharged from the hospital. Otherwise, a thoracostomy tube may be required.

In cases of a secondary spontaneous pneumothorax (caused by lung disease), if the pneumothorax is small and isn’t causing breathing difficulties, the person is likely to be admitted to hospital, given oxygen therapy, and monitored for 24 hours. If it’s a bit larger, needle aspiration may be done, followed by oxygen therapy and monitoring. However, if the pneumothorax is larger than that or causing breathing difficulties, a thoracostomy tube may be needed.

Air trapped in the pleural space (between the lungs and chest wall) can naturally be absorbed back into the body over time, which can be accelerated with supplemental oxygen. If a pneumothorax is seen to be around 25% or larger on an x-ray, and causing symptoms, needle aspiration may be needed, followed by tube thoracostomy if aspiration fails.

Surgery may be required in situations like continuous air leak for more than seven days, bilateral pneumothoraces (both lungs collapsed), for people with high-risk jobs like divers or pilots, or recurrent pneumothorax. Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery (VATS) is a common surgical procedure that can reduce the risk of pneumothorax happening again. During this procedure, a material or a chemical that is irritating to the lung lining may be introduced to cause intentional scarring, a process known as pleurodesis, which helps to prevent future episodes.

What else can Pneumothorax be?

When a doctor is trying to diagnose pneumothorax (a collapsed lung), they need to rule out other conditions that have similar symptoms. Those conditions might include:

- Aspiration, bacterial or viral pneumonia (infections in the lungs)

- Acute aortic dissection (a severe condition where there’s a tear in the wall of the aorta, the large blood vessel branching off the heart)

- Myocardial infarction (a heart attack)

- Pulmonary embolism (a blockage in one of the pulmonary arteries in the lungs)

- Acute pericarditis (inflammation of the pericardium, the two thin layers of a sac-like tissue that surrounds the heart)

- Esophageal spasm (abnormal muscle contractions in the esophagus)

- Esophageal rupture (a tear in the esophagus)

- Rib fracture (a break in one or more of the ribs)

- Diaphragmatic injuries (damage to the diaphragm, the muscle that helps you breathe)

It’s important for the doctor to consider all these possibilities and conduct necessary tests to make an accurate diagnosis.

What to expect with Pneumothorax

PSP, or primary spontaneous pneumothorax, is generally not harmful and often gets better on its own without extensive treatment. However, it can recur for up to three years. In the next five years, PSP recurs in about 30% of patients, and SSP, or secondary spontaneous pneumothorax, recurs in 43% of patients.

The risk of experiencing another pneumothorax increases with each one you’ve had, being about 30% after the first one, 40% after the second, and over 50% after the third. While PSP isn’t usually a significant health threat, there have been cases where it has resulted in death.

SSPs, on the other hand, can be more dangerous, particularly if you have underlying lung disease or a large pneumothorax. People with diseases like COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease) and HIV have a higher death rate after experiencing a pneumothorax. The mortality rate is about 10% for SSP.

The mortality rate for tension pneumothorax, a life-threatening condition where pressure builds up in the chest, is high if not quickly addressed with appropriate medical treatment.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Pneumothorax

These are some potential complications that can occur after certain medical procedures:

- Respiratory failure or arrest: This is when the breathing process stops or is not effective enough, not supplying your body with the oxygen it needs.

- Cardiac arrest: This sudden occurrence is when the heart stops beating completely and needs to be treated immediately.

- Pyopneumothorax: This is a condition of fluid and air accumulation in the cavity surrounding the lungs, which can cause lung collapse.

- Empyema: This problem is when pus accumulates in the pleural space, the area between the lungs and chest wall.

- Re-expansion pulmonary edema: This is a condition where fluid builds up in the lungs after a lung that has collapsed is re-expanded.

- Pneumopericardium: This condition happens when air leaks into the pericardium, the sac around the heart.

- Pneumoperitoneum: This event occurs when air is present in the abdominal cavity.

- Pneumohemothorax: It happens when blood and air collect in the space around the lungs.

- Bronchopulmonary fistula: This refers to a passage or hole between the bronchial tubes (that carry air to and from the lungs) and the pleural space.

- Damage to the neurovascular bundle during tube thoracostomy: This is potential harm to your nerve and blood vessels during the procedure to place a draining tube into the pleural space.

- Pain and skin infection at the site of tube thoracostomy: This is potential skin infection and pain where the tube is placed to drain fluid from the pleural space.

Preventing Pneumothorax

People who have pneumothorax (a condition where air collects in the chest cavity, leading to a collapsed lung) should be told not to fly or travel to remote locations until it’s completely healed. Those who work in high-risk professions, like scuba diving or piloting, should also be advised not to do these activities until they’ve had surgery to correct the problem.

Everyone is strongly advised to stop smoking. If a patient is willing to quit, they should be given information and support, including medication if necessary, to help them give up tobacco.