What is Pulmonary Eosinophilia?

Pulmonary eosinophilia (PE) refers to the condition where a type of white blood cell called eosinophils starts to gather in the different parts of the lungs such as the airways, the spaces between the tissues of the lungs (interstitium), and the air sacs (alveoli). This can be caused by various factors such as infections, medication, parasites, diseases where the immune system attacks the body’s own cells (autoimmune processes), cancer, and diseases that block air flow in the lungs. Increased levels of eosinophils in the lungs are linked with all these conditions.

What Causes Pulmonary Eosinophilia?

Finding a high number of eosinophils, a type of white blood cell, in the lungs isn’t exclusive to one specific disease but might hint at several possible conditions. Generally, this condition is known as ‘pulmonary eosinophilia’ and can arise from unidentified causes (primary/idiopathic), or due to known external factors (secondary/extrinsic).

If the cause is unknown, it might be due to conditions such as ‘acute eosinophilic pneumonia’ (AEP), ‘chronic eosinophilic pneumonia’ (CEP), ‘eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis’ (EGPA), or ‘hypereosinophilic syndrome’ (HES).

If it’s due to a known cause, it could be allergenic responses (like allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, ABPA), parasites, medications, radiation effects, or even tumors.

A bit more eosinophils than usual might be found in the lungs when you have sarcoidosis, idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, or ‘Langerhans cell histiocytosis’, but in these scenarios, the eosinophils just ‘happen to be there’ and don’t cause the disease.

It is also crucial to assess any medications or illicit drugs used in the weeks or months leading up to the onset of ‘eosinophilic pneumonia’ (a condition where eosinophils increase in the lungs), as certain drugs like nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, certain antibiotics, and a few others are known to cause it.

Parasites are the most common cause of eosinophilic pneumonia worldwide. There is also ‘Loeffler syndrome,’ a temporary condition where you find lung abnormalities and high eosinophils in the blood due to intestinal parasites like ascariasis and strongyloidiasis.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Pulmonary Eosinophilia

It’s challenging to determine the actual number of AEP (acute eosinophilic pneumonia) cases, as most of the information around the world comes from individual case reports and series, suggesting it’s extremely rare. Yet, it is noticeably more prevalent in men. CEP (chronic eosinophilic pneumonia) is also rare, making up less than 2.5% of all reported ILD (interstitial lung disease) cases. It’s more typical among women, who are affected twice as often as men, and it’s especially noticeable among non-smokers. The number of EGPA (eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis) cases, another condition associated with ANCA (anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody) vasculitis, remains unclear, but it’s the least common among these diseases.

Signs and Symptoms of Pulmonary Eosinophilia

Eosinophilic pneumonia (EP) requires a detailed patient history to evaluate several factors such as the presence of asthma, exposure to certain environments or occupations, travel history, medications taken, symptoms of infections, systemic findings, and the acuity or duration of symptoms. Based on specific signs and symptoms, the cause can be better identified. For instance, a skin rash may imply EGPA, HES, drug-induced, or parasitic causes, while findings of heart muscle disease could indicate involvement of EGPA or HES. Conditions like EGPA or ABPA could also result in upper airway issues.

Acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP) typically has a sudden onset within days to weeks of experiencing symptoms like shortness of breath, cough and fever. There’s usually no identifiable causes of eosinophilic pneumonia from the patient’s history, such as specific drugs. AEP commonly affects men, particularly those with no history of asthma. Contrarily, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP) is mostly seen in women and non-smokers, though the cause remains unknown, it seems to occur more frequently in people with asthma or a history of atopic disease. It generally presents itself over several months with symptoms like shortness of breath, cough or chest pain, and possibly associated constitutional symptoms.

Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (EGPA) usually occurs around the age of 35 and is marked by a history of severe asthma that is dependent on corticosteroids. Up to 75% of these patients could have rhinitis and sinusitis. Additionally, they could experience symptoms of heart failure, kidney failure, neuropathy, and palpable purpura due to multisystem vasculitis.

Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES) shows non-specific symptoms like a cough and shortness of breath. These patients may also exhibit signs and symptoms of heart failure, central nervous system complaints, peripheral neuropathies, and skin changes such as hives and swelling.

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis (ABPA) tends to occur in patients with poorly controlled asthma or cystic fibrosis. Symptoms include a productive cough sometimes with brownish sputum and wheezing.

Loeffler syndrome is found in temperate and tropical climates and is typically marked by coughing, wheezing and fever. Meanwhile, Tropical eosinophilia is common among young adult males living in Asia or Africa, with symptoms often including a dry cough that worsens at night accompanied with wheezing.

Testing for Pulmonary Eosinophilia

If your doctor suspects that you might have a condition involving inflammation in the lungs due to high levels of a certain type of white blood cell called eosinophils, they will need to conduct several tests. These tests may include lab tests such as a full blood count test to check for certain antibodies. You might also be asked to provide a stool sample to test for certain parasites.

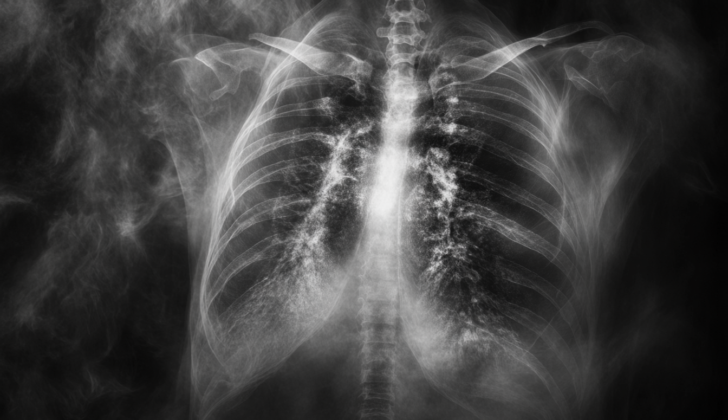

To get more detailed information about your lungs, they may also arrange for a test called pulmonary function testing or an imaging test called a CT scan.

Your doctor can diagnose eosinophilic pneumonia (a type of lung inflammation due to eosinophils) in one of three ways:

1. By observing an increased number of eosinophils in your blood along with areas of shadowing in your lungs on an imaging test.

2. Through a bronchoscopy, a procedure that involves collecting and analyzing a fluid sample from your lungs. If more than 25% of the cells in this sample are eosinophils, it might indicate eosinophilic pneumonia.

3. By performing a lung biopsy, a procedure where a small piece of lung tissue is removed and analyzed.

Sometimes a specific diagnosis can be made from your medical history, symptoms, and the results of the tests. For example, in patients with hard-to-control asthma, the doctor might suspect a condition called allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA). Testing for ABPA would include testing for specific antibodies and substances in your blood, and perhaps additional imaging of your lungs with a CT scan.

Sometimes, the inflammation in your lungs can be triggered by a medication you’re taking. Your doctor might suspect this if your symptoms improve when you stop taking the drug. However, in most cases, it’s not practical to rechallenge with the drug to confirm the diagnosis.

In some cases, your symptoms and test results might suggest that you have a chronic (long-term) form of eosinophilic pneumonia. In other cases, the findings might suggest a condition called EGPA, which involves inflammation and damage to various organs due to an overactive immune system.

If your symptoms persist for more than six months and are accompanied by high eosinophil levels, your doctor might suspect a condition called hypereosinophilic syndrome. This condition can cause damage to various organs, including the lungs.

If you’ve recently traveled to certain areas or come from a region where certain parasites are common, your doctor might suspect a parasitic infection as the cause of your symptoms. They might order additional blood and stool tests to check for this.

Overall, your doctor will use all the information gathered from your history, symptoms, and various tests to try to determine the cause of your lung inflammation.

Treatment Options for Pulmonary Eosinophilia

Eosinophilic Pneumonia or EP is a lung disease that’s caused by a variety of factors. The treatment for EP is usually aimed at addressing the root cause of the problem. Depending on the cause, different treatment methods will be used.

For instance, if a patient has a history of exposure to parasites and a blood test confirms this, a trial of an anti-parasitic medicine like mebendazole might be given.

If a patient is suffering from an acute or sudden attack of EP, a course of corticosteroids, a type of anti-inflammatory drug, may be given through a vein. This usually results in a rapid health improvement, often only within 12 to 48 hours. After this initial treatment, the patient is then switched to oral steroids which are gradually reduced over a period of 2 to 4 weeks.

For chronic or long-term EP, steroids also show very good results, improving the symptoms and lung X-ray results within days to weeks. While there’s no fixed dosage for corticosteroids, a common plan is to start the treatment with prednisone, a specific kind of corticosteroid, at a specific dose. It is common to need this treatment for longer periods since the EP could return if the daily prednisone dose is reduced below a certain level. Note that only around 30% of patients are able to completely stop prednisone treatment in their lifetime.

In cases of a certain kind of EP, known as ‘EGPA’, steroids are largely used. Some patients may receive very high doses of a particular type of steroid called methylprednisolone or another type of steroid called prednisone, which is gradually reduced over several months. But in severe cases, or if the disease has affected multiple organs like the heart, kidneys, or digestive system, another drug called cyclophosphamide might be used to reduce the need for steroids.

For patients with a specific form of EP, called Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES), a drug called Imatinib is usually the first choice for treatment, particularly for those patients with the myeloproliferative variant of HES. Steroids may also be used, particularly in the ‘lymphocytic variant’ of HES, although only about half the patients respond. However, a recent study showed that an anti-IL-5 antibody called mepolizumab helps reduce the reliance on steroids.

For ABPA, a type of allergic lung inflammation, oral corticosteroids are the main treatment. Recent studies suggest that an antifungal drug called itraconazole can provide additional benefits. The steroid treatment is usually reduced over a few months.

For tropical pulmonary eosinophilia, a condition commonly seen in tropical regions, a drug called diethylcarbamazine is the first choice for treatment. If the cause of EP is due to parasitic worm infections like ascariasis or strongyloides, then specific anti-parasitic drugs like mebendazole, albendazole, or ivermectin are used. This is due to the risk of these infections causing hyperinfection in the future.

What else can Pulmonary Eosinophilia be?

Here’s a simple-to-understand list of various health conditions:

- Intestinal fibrosis (thickening and scarring of tissue in intestine)

- Intestinal flukes (parasitic worm infections in the gut)

- Mediastinal lymphoma (a type of cancer in the area between the lungs)

- Mucormycosis (a rare, potentially dangerous fungal infection)

- Nematoda infections (infections caused by a type of parasitic worms)

- Respiratory failure (condition where the lungs can’t get enough oxygen into the blood)

- Sarcoidosis (inflammation that produces tiny lumps of cells in various organs)

- Scleroderma (a group of rare diseases that involve hardening and tightening of the skin and connective tissues)

- Tuberculosis (an infectious disease that primarily affects the lungs)

- Zygomycosis (another term for mucormycosis, a serious fungal infection)

What to expect with Pulmonary Eosinophilia

Acute Eosinophilic Pneumonia (EP), a type of lung inflammation, often shows up a lot like sudden severe breathing difficulties (acute respiratory distress syndrome). However, treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs called corticosteroids usually leads to quick recovery with no long-lasting effects or recurring symptoms once treatment stops. On the other hand, recurring bouts are common with chronic EP, which often calls for extended treatment with corticosteroids.

In Chronic Eosinophilic Pneumonia (CEP), most patients need a long-term course of corticosteroids and symptoms frequently return when the dose is reduced. A similar pattern is observed in Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (EGPA), where recurring bouts are common, and asthma often continues. Those affected by EGPA with heart involvement tend to have a worse prognosis.

In the past, life expectancy was quite poor for those with Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (HES), a group of rare blood disorders. But now, with advancements in medicine, survival rates have greatly improved with 70% to 80% of patients living for at least 10 years. Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis (ABPA), a lung condition, can vary and symptoms can come back after treatment. In some cases where flare-ups are very frequent, long-term use of corticosteroids may be necessary.