What is Aseptic Meningitis?

Aseptic meningitis is a condition where the protective layers of the brain and spinal cord, called meninges, become inflamed. This inflammation can be caused by various factors and is usually identified by a test involving the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the fluid in our brain and spine. If there’s an increase in the number of white blood cells in the CSF, more than 5 per cubic millimeter to be exact, it’s a clear sign of this condition. Aseptic meningitis is a common condition and is typically benign, meaning it does not result in serious harm.

There are many causes for aseptic meningitis. It’s usually caused by viruses like the herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), enteroviruses, and arboviruses. However, it can also be caused by other factors like certain bacterial, fungal and spiral-shaped infections, infections near the meninges, certain medications, and even cancer. It’s important to note that aseptic meningitis and viral meningitis are not the same thing, pointing out the various causes of the inflammation. The symptoms can vary greatly depending on the cause and the immune system of the affected individual. People who have weak immune responses, such as newborns and those with a lack of certain antibodies, face a particularly high risk of complications from aseptic meningitis.

What Causes Aseptic Meningitis?

Aseptic meningitis can be caused by both infectious and noninfectious factors. Despite advances in diagnosis, only about 30% to 65% of all cases can be traced back to a specific cause. Those without a known cause are called “idiopathic”.

Infectious causes of aseptic meningitis are numerous, including viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites. Viruses are the most common infectious agents. Examples include enteroviruses, which are responsible for over half of cases, HSV-2, West Nile virus, and varicella-zoster virus. Other viruses related to aseptic meningitis are the various respiratory viruses, mumps virus, arbovirus, HIV, and the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus.

Bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections can also lead to aseptic meningitis but are less common than viral causes. Fungal infections can be caused by the likes of Candida, Cryptococcus neoformans, Histoplasma capsulatum, and others. In terms of parasitic causes, these include Toxoplasma gondii and naegleria, among others.

When it comes to noninfectious causes, these can be grouped into three main categories: systemic diseases, drug-induced causes, and neoplastic (cancer-related) causes. Systemic diseases include conditions like sarcoidosis, Behçet disease, and Sjögren syndrome. The drug-induced causes are often linked to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), some antibiotics, intravenous immunoglobulin, and some monoclonal antibodies. Neoplastic meningitis is usually related to metastasis from solid tumours or lymphoma/leukemia.

Interestingly, vaccines can also trigger aseptic meningitis. This has been documented with vaccines for conditions such as measles, mumps, rubella, varicella, and influenza. Some reports also suggest it could occur after meningococcal vaccination.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Aseptic Meningitis

Aseptic meningitis is an underreported condition that can affect people of all ages, but it is more common in children than adults. Every year, in the United States, about 11 out of every 100,000 people get aseptic meningitis. Adults have a slightly lower rate of 7.5 per 100,000 people, and it’s found to be three times more common in men than women. This health issue doesn’t favor a particular age group or race.

- Each year, aseptic meningitis leads to 26,000 to 42,000 hospital stays in the US.

- Research from Europe shows an incidence rate of 70 per 100,000 for children under the age of one, 5.2 per 100,000 for children aged one to 14, and 7.6 per 100,000 for adults.

- A study from South Korea found similar rates across all age groups in children, with higher rates in those under one year and those aged 4 to 7. This study also showed a male-to-female ratio of 2 to 1.

- While aseptic meningitis can happen at any time of the year, it’s commonly observed in the summertime in places with moderate climates.

Signs and Symptoms of Aseptic Meningitis

Figuring out the cause of a health problem isn’t always straightforward. Some illnesses share similar symptoms, so it’s important for doctors to have a thorough understanding of the patient’s medical history. This can include questions about exposure to sick people, recent travel, use of substances, sexual history, recent infections, and past medication use. Doctors also consider the possibility of illnesses caused by medicines themselves, such as drug-induced aseptic meningitis.

When it comes to assessing patients, it’s important to be aware that the symptoms can vary from person to person. In adults, they often report headaches, nausea, vomiting, general discomfort, weakness, stiff neck, and an extreme sensitivity to light. These symptoms can come on more slowly and without causing mental confusion, unlike bacterial meningitis.

On the other hand, children’s symptoms tend to be less specific. They might have a fever, respiratory issues like coughing or a runny nose, a rash, and show signs of being irritated or fussy. Young babies could have a bulging spot on their head and be very irritable. Factors such as being born premature, the mother having a sickness, high white blood cell count, low hemoglobin levels, and development of symptoms within the first week of life require immediate attention in newborns.

- Restricted neck flexibility (70% sensitivity)

- Fever (85% sensitivity)

are common physical symptoms seen in both children and adults. Kernig and Brudzinski’s signs, physical symptoms that can be but aren’t exclusively linked to meningitis, are very specific (95%), but aren’t reliable due to their extremely low sensitivity (5%). Depending on the root cause, other associated physical signs might be present.

Testing for Aseptic Meningitis

Recent advancements in technology, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and next-generation sequencing, have improved our ability to identify the exact causes of aseptic meningitis, a condition where the protective layers around the brain become inflamed. These advancements also help identify autoimmune and paraneoplastic neurological syndromes.

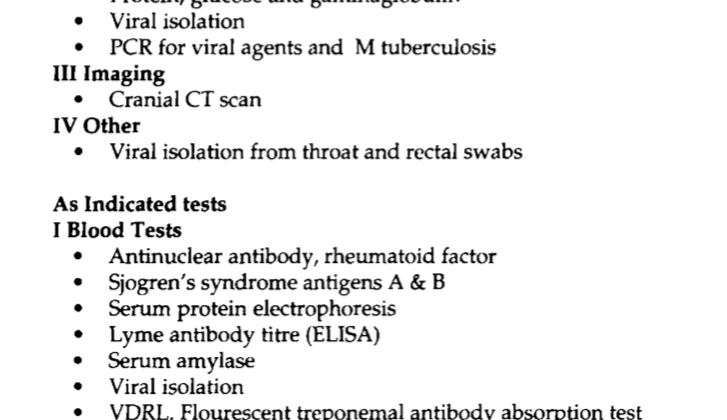

Typically, the first step in diagnosing aseptic meningitis is conducting laboratory tests to rule out other potential causes of the symptoms. This usually involves a complete blood count, a test to measure the speed that your red blood cells gather at the bottom of a test tube of blood (erythrocyte sedimentation rate), and tests to detect enterovirus, adenovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and the herpes simplex virus (HSV).

To definitively diagnose aseptic meningitis, doctors perform a lumbar puncture to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which surrounds the brain and spinal cord. This fluid is examined for cell count, glucose and protein levels, and for harmful organisms. Additionally, various PCRs are performed to target specific bacteria or viruses.

Oftentimes, patients with aseptic meningitis present with normal or slightly heightened CSF opening pressure, glucose, and protein levels. The cell count can, however, range between 10 and 1000 cells per microliter, with an initial prevalence of neutrophils, a type of immune cell, shifting towards lymphocytes, another type of immune cell.

Interestingly, adults and children present with different symptoms and laboratory findings and therefore require diagnosis and treatment methods tailor-made to each age group. For example, adults commonly report headaches and have neck stiffness, while children often have fever, respiratory illness, and rashes.

Given these differences in presentation, it is important to apply age-adjusted values when interpreting CSF fluid results, especially in newborns and young infants. For example, in children with aseptic meningitis, the CSF can often exhibit a prevalence of neutrophils.

In cases of aseptic meningitis caused by medications, the symptoms can often be minimal. Thus, it’s important for doctors to thoroughly explore the patient’s medical history, including medications and their dosages.

Separating aseptic from bacterial meningitis can be tricky, but there are tools developed to aid in diagnosis. The bacterial meningitis score is noteworthy as it is highly sensitive and moderately specific. Other findings in lab tests, such as blood levels of procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, and CSF lactate levels can also be helpful.

Before performing a lumbar puncture, if there is a risk of high pressure within the skull due to lesions or inflammation, it is recommended to conduct a computed tomography (CT) scan of the head. The CT scan can aid in finding an alternative diagnosis and might remove the need for a lumbar puncture. However, for newborns and infants, a head ultrasound is preferred over a CT scan.

Moreover, studies have shown that imaging might be safely avoided if patients do not meet certain criteria, including being 60 years old or older, a history of neurological disorders, a compromised immune system, altered mental state, seizures within the last week, or any neurological deficits. This helps healthcare professionals make strategic decisions regarding the use of imaging resources.

Treatment Options for Aseptic Meningitis

Recognizing the cause of meningitis early on is key to starting treatment promptly. Part of the initial treatment involves giving the patient intravenous fluids over the course of 48 hours. If bacterial meningitis is suspected, doctors must quickly start antibiotics that are effective against the most likely germs. This depends on the age of the patient, especially in children.

Normally, doctors should collect some cerebrospinal fluid (CSF, the fluid protecting the brain and spine) before giving antibiotics. However, if getting this fluid would slow down treatment or if the patient is very sick, antibiotics should be started right away. It’s also important to prevent the spread of infection, so the patient should be isolated until doctors confirm what’s causing the disease. If the Herpes Simplex Virus or Varicella Zoster Virus (the virus that causes chickenpox and shingles) might be the cause, antiviral medicine like acyclovir would be part of the initial treatment.

If the test results suggest that the meningitis isn’t caused by bacteria, doctors might stop the antibiotics. However, this decision would be based on the patient’s symptoms and health. The main treatment for most kinds of viral meningitis is supportive care, meaning treating symptoms to help the patient feel better. Treatments for other kinds of meningitis, caused by things like bacteria or fungi, would depend on the patient’s specific symptoms and health conditions.

Steroids can be used along with other treatments to mitigate the inflammation. Dexamethasone, a type of steroid, can be given 10 to 20 minutes before or at the same time as antibiotics. Research shows that the use of steroids can reduce the risk of complications like neurologic problems and hearing loss, especially in cases of bacterial meningitis.

If a patient’s condition doesn’t improve after 48 hours, doctors might do another CSF fluid test. Regular monitoring of the patient’s neurologic status is essential to figure out the best plan of action and ensure the best care possible.

Once doctors have confirmed a diagnosis of non-bacterial meningitis and made sure that the patient is stable, the patient can usually go home. There are some exceptions, like older adults, people with weakened immune systems, and children with too many white blood cells in their CSF fluid, who may need to stay in the hospital. When discharging a patient, their instructions for home care would depend on the specific cause of their meningitis. For example, patients with enterovirus should wash their hands regularly and avoid sharing food because the virus is mainly spread through the fecal-oral route.

Pain management and fever control are important for all patients with meningitis. Over-the-counter drugs can help with this. In cases where a medication has caused the meningitis, the offending drug must be stopped. If needed, another drug that won’t irritate the meninges (the protective layers covering the brain and spine) could be used instead.

What else can Aseptic Meningitis be?

The signs of a condition called aseptic meningitis can often be unclear or generic, which means there are many potential diagnoses. Two of the most common symptoms are headache and fever.

One major condition to consider is bacterial meningitis, which is a serious and common condition often confused with aseptic meningitis. It’s the first condition doctors look at until they can rule it out. Patients might also need to be checked for internal bleeding in the skull, particularly subarachnoid hemorrhage. Moreover, certain cancers like leukemia and brain tumors, types of headaches like migraines, or inflammation in the brain such as a brain abscess should all be considered when diagnosing.

Fever can come from almost any source and is often associated with headache and a stiff neck. Other conditions, like urinary tract infections and pneumonia, could also lead to headaches, body aches, and fever. Therefore, it’s important for doctors to thoroughly examine the body for sources of infection when trying to diagnose.

Some causes of aseptic meningitis might show many, or even all the symptoms, even without actual inflammation of the meninges (the protective layers around the brain). Particularly, viral syndromes often lead to symptoms like headaches, muscle aches, weakness, and fever even without this inflammation.

So, the list of potential diagnoses is quite broad and includes conditions like anemia, which is known to cause headaches and weakness. It even includes conditions like carbon monoxide exposure, child abuse, illnesses transmitted by ticks, and tuberculosis. This shows just how many possibilities doctors must consider while diagnosing.

What to expect with Aseptic Meningitis

The outcome of aseptic meningitis, a type of meningitis, greatly depends on the person’s age and the cause of the condition. Viral meningitis is generally less severe, with most people fully recovering within 5 to 14 days. Any lingering symptoms are typically mild and may include tiredness and feeling lightheaded.

However, other types of viruses and non-viral causes of meningitis, such as the herpes viruses, can be more serious. Tuberculosis meningitis, in particular, is complex and poses a high risk of sickness and death if not promptly identified and treated.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Aseptic Meningitis

Aseptic meningitis, an inflammation of the protective coverings of the brain and spinal cord, can cause serious problems like seizures. In extreme cases, it may even lead to a severe form of epilepsy known as status epilepticus. Despite the serious nature of these complications, prevention is usually not recommended. On the other hand, if bacterial meningitis is expected but not treated promptly, long-term neurological issues such as hearing loss may result.

Encephalitis, which is inflammation of the brain, can sometimes occur at the same time as viral meningitis, causing a variety of symptoms. For example, Mumps meningoencephalitis, a combination of mumps infection and inflammation in the brain, can cause issues like sensorineural deafness and aqueductal stenosis, leading to an abnormal accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid, also known as hydrocephalus. Similarly, TB meningitis can lead to a host of complications.

- Hydrocephalus

- Infarcts, which are smaller areas of dead tissue due to lack of blood

- Epilepsy

- Mental regression, a reverse development in mental abilities

- Neurological deficits, impairment in the function of the nervous system

- Cranial nerve palsies, or weakness in cranial nerves

Preventing Aseptic Meningitis

After initially diagnosing and treating an illness, it’s vitally important to prevent the spread of infectious agents. This can be achieved by following strict isolation instructions, often related to protection from airborne particles, and washing hands frequently. These are key methods for stopping the spread of conditions like viral meningitis, and many other infections. Particular care should be taken after changing children’s diapers, to stop the spread of certain viruses.

Thorough hand-washing is crucial, and isolation should be put in place based on what infection is suspected. One of the most important prevention methods is vaccination. Vaccines exist for those at risk of conditions like polio, measles, mumps, chickenpox and rubella. There’s a recommended schedule for these vaccinations to be followed. Also, vaccines for certain mosquito-borne viruses are available for people who live in or travel to areas where those viruses are common.