What is Cranial Nerve III Palsy?

The third cranial nerve, also known as the oculomotor nerve, has two main parts:

1. The outer fibers, which control the muscles in our eyes that help us focus and adjust the size of our pupils.

2. The inner fibers, which control the muscle in the eyelid that lifts the upper eyelid, and four muscles that help move our eyes.

There’s a handy memory trick, “LR6(SO4)3”, to remember which muscles our nerves control. Here’s what it stands for:

“LR6” refers to the Lateral rectus muscle, a muscle that helps move the eye. This one is controlled by the sixth cranial nerve.

“SO4” stands for the Superior oblique muscle, another eye-moving muscle. The fourth cranial nerve controls this one.

The “3” reminds us that the third cranial nerve controls the other muscles that help our eyes move.

What Causes Cranial Nerve III Palsy?

Third-Nerve Palsy, or TNP, can be caused by several things. These include reduced blood flow to the nerve (ischemia), injury, tumors in the brain, bleeding, birth defects, or sometimes the cause is unknown. Diabetes and high blood pressure can cause ischemia in the nerve, making these two conditions the most common causes of this kind of nerve damage.

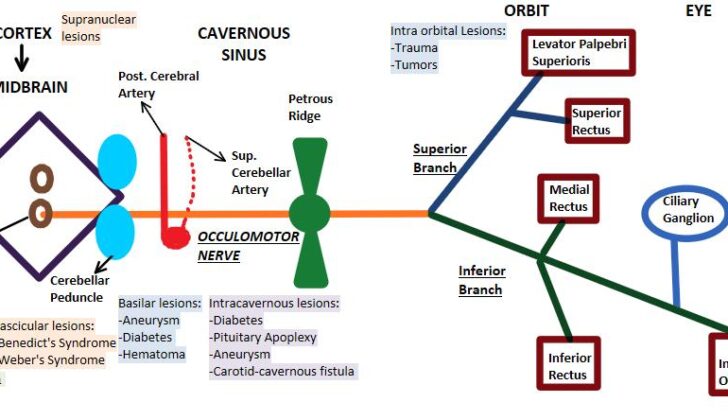

Depending on where the damage occurs on the nerve, the cause and symptoms can be different:

- Supranuclear lesions: If there are lesions in the cerebral cortex or the supranuclear pathway, both eyes will have difficulty moving together.

- Nuclear lesions: These are usually caused by vascular diseases, loss of the protective layer around the nerve (demyelination), and tumors.

- Fascicular lesions: These are caused by the same conditions as nuclear lesions.

If the damage is in the basilar portion of the nerve, TNP often occurs on its own. The main causes in this area are aneurysms, diabetes, and extradural hematoma, a type of bleeding outside the brain’s outer covering. TNP can be caused either by an aneurysm pressing directly on the nerve, or by bleeding near the aneurysm. This results in isolated and painful TNP. An extradural hematoma can cause the same pressure that leads to TNP.

In the intracavernous portion of the nerve, there are several other nerves nearby, so any damage here can cause multiple palsies involving several cranial nerves. The usual causes here are diabetes, pituitary apoplexy (bleeding or impaired blood supply the pituitary gland), aneurysm, or carotid-cavernous fistula (an abnormal connection between a large artery and vein in the brain). In the intraorbital portion, TNP is mainly caused by trauma, tumors, and Tolosa-Hunt syndrome, a rare inflammatory condition.

In children, all cases of TNP should be thoroughly investigated to rule out any tumors. Other common causes in children include birth defects (43%), local inflammation (13%), injuries (20%), aneurysms (7%), Myasthenia gravis (a chronic autoimmune neuromuscular disease), and migraines. It’s also important to check for any vision problems in children who have strabismus (a condition that causes the eyes to not properly align with each other) after they’ve been given medicine that dilates their pupils.

Birth defects of TNP can be due to a poorly developed or missing oculomotor nucleus (part of the brain that controls eye movements), birth trauma due to pressure on the skull during labor, trauma before birth, and rarely infections such as meningitis.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Cranial Nerve III Palsy

Third-nerve palsy is a serious condition that can signal life-threatening issues like aneurysms. Studies show that third-nerve palsy is associated with aneurysms in about 10% of cases, and can affect both eyes in 11% of patients. This condition affects both men and women almost equally, and is less common in children and young adults. People over the age of 60 are the most affected group. It’s also worth noting that at the time of diagnosis, 43% of patients exhibit pupil involvement and 86% of patients show drooping of the upper eyelid. In the US, the rate of third-nerve palsy is estimated to be 4 out of every 100,000 people.

- Third-nerve palsy can be a sign of life-threatening aneurysms.

- About 10% of third-nerve palsy cases are due to aneurysms.

- Both eyes are affected in 11% of patients.

- Men and women are almost equally likely to get third-nerve palsy.

- It is less common in kids and young adults.

- People over 60 are the most likely to get third-nerve palsy.

- Pupils are affected in 43% of cases, and 86% of patients have a drooping eyelid when first diagnosed.

- In the US, third-nerve palsy occurs in 4 out of every 100,000 people.

Signs and Symptoms of Cranial Nerve III Palsy

When someone is suffering from paralysis of the third-nerve, there are some key signs and symptoms that medical practitioners look for. These include:

- Ptosis, or drooping of the eyelid, caused by muscle paralysis

- Ocular deviation, where the eye moves into a “down and out” position due to unbalanced muscle action

- A fixed and dilated pupil due to paralysis of the muscle that controls its size and function. This same condition can also cause loss of eye focus control. In cases of ischemic lesions, however, the pupil and accommodation remain unaffected.

- Diplopia, or double vision. This happens when the affected eye deviates and the image falls off center. Interestingly, most people don’t notice the double vision because the concurrent droopy eyelid blocks it.

Furthermore, this condition is often associated with four distinctive syndromes, each presenting a unique combination of symptoms:

- Benedikt syndrome: Signs include third-nerve palsy on the same side and tremors on the opposing side

- Weber syndrome: Characterized by third-nerve palsy on one side and paralysis on half of the body on the other side

- Nothnagel syndrome: This presents as third-nerve palsy on one side and loss of muscle coordination due to cerebellar damage, also called ataxia

- Claude syndrome: A combination of symptoms presented by Benedikt and Nothnagel syndromes

Testing for Cranial Nerve III Palsy

If you have symptoms that suggest a condition called pupil-sparing third-nerve palsy, medical professionals will want to make sure it’s not because of a problem with your blood vessels. They may ask for certain tests such as recording your blood pressure, a complete count of the different cells in your blood, blood sugar and Hb1AC (a measure of your average blood sugar levels over the past 2 to 3 months), and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) that measures inflammation in your body.

If the condition is not pupil-sparing, it means the issue is more serious and an immediate evaluation by an eye and brain specialist should be done. An MRI, a type of scan that uses magnetic fields and radio waves to create images of your body, is typically more efficient than a CT scan at spotting any abnormal changes in your brain.

The MRI usually focuses on the brainstem by using thin sections and a certain type of imaging called T2-weighted imaging. This makes the nerve appear as a dark line amidst the bright signal produced by the fluid surrounding your brain and the spinal cord. If doctors suspect you might have an aneurysm (a bulge in a blood vessel due to a weak wall), they will rapidly organize a special type of CT scan known as CT angiography. This scan uses dye and x-rays to look at blood vessels in your brain.

Treatment Options for Cranial Nerve III Palsy

Conservative treatment is often recommended as a short-term solution for acute paralysis, especially for people over the age of 50 who have a history of diabetes or high blood pressure. Regular check-ups every three months are necessary to monitor any signs of recovery. People with ischemic third-nerve palsy, a condition affecting eye movement, typically begin to improve within the first month and generally recover fully within three months. If double vision occurs, an eye patch or special contact lens can cover the affected eye.

In children, alternating eye patching can prevent a condition called amblyopia from developing due to drooping eyelids or misaligned eyes. A treatment involving an injection of botulinum toxin into the lateral rectus muscle has been suggested to correct partial third-nerve palsy. This toxin causes temporary paralysis of the muscle, which helps to correct outward deviation of the eye.

In cases where the condition doesn’t improve after six months and the pupil remains unaffected, surgical treatment might be necessary. These surgeries aim to align the eye properly in its resting gaze and ensure a single, focused field of vision. But, operating to fix this type of nerve palsy is complicated.

Before surgery can correct a drooping eyelid, the eye needs to be properly aligned to prevent double vision. The specific surgical options depend on the extent of the palsy – whether it’s complete or partial. The more intensive surgery for complete third-nerve palsy involves adjusting the related eye muscles and may also require a tendon transposition.

In cases of partial third-nerve palsy, surgeries are dependent on how much the eye muscles have been affected. Once the misalignment of the eye is treated, then the drooping eyelid can be corrected. If the nerve palsy affects the pupil, further investigation is required, and it is advisable to consult with a neurologist.

What else can Cranial Nerve III Palsy be?

- Ophthalmoplegic migraine[15] – a rare condition characterized by a migraine headache followed by temporary vision disturbance.

- Internuclear ophthalmoplegia – a disorder that affects eye movement and coordination between the two eyes.

- Ptosis in adults or congenital ptosis – a drooping of the upper eyelid, which can be present from birth (congenital) or develop later in life (adults).

- Anisocoria – a condition where one pupil is larger than the other, leading to unequal size of the pupils.

- Myasthenia gravis – a long-term condition causing muscle weakness that can affect vision by impacting the muscles that control eye movements.

- Thyroid ophthalmopathy – an eye condition that occurs when the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks the muscles and other tissues around the eyes. This is often seen in people with thyroid problems.

What to expect with Cranial Nerve III Palsy

In most instances of third-nerve palsy, the outlook is generally positive, as symptoms often decrease on their own over several months. However, the measure of recovery relies on the cause of the problem and its treatment.