What is Hydrocephalus?

Hydrocephalus is a condition where cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which is a type of liquid, builds up inside the chambers of the brain known as “ventricles.” This buildup can happen due to a blockage in the fluid’s flow, problems with how the fluid is absorbed back into the blood circulation, or if too much fluid is produced.

Dr. Dandy first classified hydrocephalus as “communicating” and “non-communicating” or obstructive in 1913. Since then, other types have been identified, especially in adults. These include obstructive, communicating (meaning the fluid can still flow between certain areas of the brain), hypersecretory (too much fluid is produced), and normal pressure hydrocephalus (the fluid causes pressure, but it is not higher than the usual). Additionally, babies can be born with hydrocephalus, which is usually linked to a genetic condition or an issue with the spine’s development.

Surgery to place a shunt, or tube, to drain the fluid is usually the first treatment option. However, in specific forms of hydrocephalus, other surgical procedures like an endoscopic third ventriculostomy (creating a hole in a ventricle) or choroid plexus cauterization (burning tissue to reduce fluid production) might be suitable. If hydrocephalus becomes severe and isn’t treated quickly, it can lead to serious brain injuries and even death. In children, the death rate from hydrocephalus can be up to 3%, depending on how long they’ve had the condition and whether they receive treatment in time.

What Causes Hydrocephalus?

Obstructive hydrocephalus is a condition that develops when there’s a blockage in the passages that fluid in your brain flows through. This fluid, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), can be blocked in several areas in the brain, often at places called the foramina Monro, the aqueduct of Sylvius, the fourth ventricle, and foramen magnum. However, larger tumors can cause blockages anywhere in these fluid pathways. Tumors like ependymoma, subependymal giant cell astrocytoma, choroid plexus papilloma, and others are often associated with hydrocephalus. Particularly, tumors in the lower back part of the brain, the posterior fossa, are commonly related to developing hydrocephalus.

Another type of hydrocephalus is called communicating hydrocephalus, and it’s caused by the brain not being able to absorb the CSF properly. Common causes for this include changes after a hemorrhage or inflammation. Subarachnoid hemorrhage, a type of stroke caused by bleeding on the surface of the brain, accounts for a third of these cases by blocking absorption of CSF. Infections of the protective layers of the brain, like bacterial meningitis, can also be complicated with hydrocephalus. Also, head injuries are a major contributor to hydrocephalus in adults.

There’s also a type called hypersecretory hydrocephalus, which is caused by overproduction of the CSF. This is often due to a tumor called a plexus papilloma, or less commonly a type of cancer, carcinoma. These tumors are more commonly found in children.

Normal-pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) is a type of communicating hydrocephalus that becomes more common in older age. It’s caused by issues with the flow of the CSF, despite having normal or slightly increased pressure in the brain. The causes for NPH are not yet fully understood.

Additionally, babies can get hydrocephalus too due to prenatal hemorrhage or infection. Some inherited forms of hydrocephalus may not be noticeable at birth. Nearly 10% of all cases of hydrocephalus in newborns are due to a malformation of the brainstem, causing a narrowing of the cerebral aqueduct, one of the fluid pathways in the brain. Other conditions such as Dandy-Walker malformation and Arnold-Chiari type 1 and type 2 syndromes are common causes of hydrocephalus in newborns.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus is a condition most prevalent in babies due to birth defects and bleeding inside the ventricles of premature infants. However, it can also be a problem for older adults due to a condition called Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH). Worldwide, about 85 in 100,000 people are affected by this disease.

- The rates vary based on age groups, with 88 in 100,000 in children and 11 in 100,000 in adults.

- Older people are more prone to it, with an occurrence of about 175 in 100,000, increasing to 400 in 100,000 for those aged 80 and over, mainly due to NPH.

- Africa and South America have a higher prevalence of this condition.

- Around 1 to 32 in every 10,000 births result in infant hydrocephalus.

- It impacts both males and females equally.

Signs and Symptoms of Hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus is a condition often diagnosed based on a mix of physical symptoms, brain scans, and fluid pressure readings. Its symptoms can vary depending on factors like the patient’s age, the cause of the condition, where the fluid buildup is happening, and how quickly it develops. Different types can present with different symptoms.

In acute hydrocephalus, symptoms progress rapidly and can be severe. Left untreated, it can lead to serious complications like brain herniation. This may present as a dilated and nonresponsive pupil, dysfunctional autonomic nervous system, loss of brain stem reflexes and coma. Emergency medical treatment is needed in these situations.

Children born with hydrocephalus (congenital hydrocephalus) typically have an unusually large head, among other symptoms:

- Bulging fontanelle (soft spot on the top of the head)

- Thin and shiny scalp with visible veins

- Stiff arms and legs

- “Setting sun” look (pupils are close to the lower eyelid)

- Breathing difficulties

- Poor feeding

- Unwillingness to move the neck or head

- Delayed development

- “Cracked pot” sound when tapping the skull, known as Macewen sign.

Additional symptoms can be irritability, vomiting, seizures, and a failure to look upward. In severe untreated cases, more serious symptoms of dorsal midbrain syndrome (Parinaud syndrome) may develop.

Acquired hydrocephalus, which can develop at any age, has its own set of symptoms. These can include:

- Headache and neck pain

- Nausea and vomiting

- Drowsiness and lethargy

- Irritability

- Seizures

- Confusion and disorientation

- Blurred vision and double vision (diplopia)

- Urinary and bowel incontinence

- Problems with balance and walking

- Lack of appetite

- Changes in personality and memory.

In the case of normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH), the typical symptoms are problems with walking, dementia, and urinary incontinence. These conditions might take months or even years to develop and in the late stages, patients might exhibit abnormal reflexes.

Testing for Hydrocephalus

If you, or your child, have been born with hydrocephalus, your doctor might recommend genetic counseling and testing. This can help to understand the cause and suggest ways to treat and manage it.

Testing the cerebrospinal fluid (or CSF – a clear substance that surrounds the brain and spinal cord), can also be helpful for diagnosing hydrocephalus and checking for any ongoing infection.

Doctors might sometimes use X-rays of the head, which can show certain abnormalities related to hydrocephalus like an eroded ‘sella turcica’ (a depression in the skull bone) or a specific pattern on the skull known as a ‘beaten copper cranium.’ These tests are not commonly used given that more advanced imaging techniques are available and provide a more accurate picture.

For babies, a technique called ultrasonography can be used. This involves sending sound waves through the soft spot in the baby’s head, known as the anterior fontanelle, to get a picture of the brain. This can help check the size of the brain’s ventricles (fluid-filled spaces), which can become enlarged with hydrocephalus.

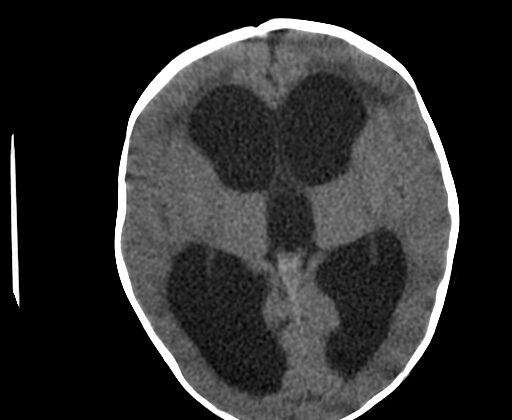

Images of the brain are fundamental in confirming a diagnosis of hydrocephalus. If hydrocephalus develops suddenly (acute hydrocephalus), a type of brain scan known as a CT scan is needed urgently to measure the size of the ventricles. One sign that might show up on this scan is ‘periventricular hypoattenuation,’ which appears as dim areas around the ventricles due to excess fluid. Enlarged ventricles can also create a pattern resembling Mickey Mouse’s head, which often indicates a blockage in the brain’s fluid passages.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging or MRI is usually the preferred way to evaluate the brain as it provides a more detailed image. It is especially useful for understanding the cause of hydrocephalus, identifying any possible treatments, and distinguishing between different brain conditions. It can detect excess fluid around the ventricles (known as periventricular hyperintensity) and help differentiate it from age-related changes in the brain’s white matter.

In cases where hydrocephalus has developed over a long time (chronic hydrocephalus) certain signs may not be as prominent and the brain might show signs of shrinkage. The MRI can also be used to measure fluid movement in the brain’s passages using a technique called MRI cine, but this is not usually helpful in predicting whether fluid-removing surgery (shunting) would be beneficial.

Radionuclide cisternography is a type of imaging test occasionally used to evaluate a kind of hydrocephalus that primarily affects adults and older people (NPH) and help predict whether shunting would be of benefit. However, this test isn’t commonly used because it doesn’t always give clear information.

Treatment Options for Hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus is a condition where fluid builds up in the brain, and if it’s not treated, it can cause permanent brain damage, physical and mental problems, and possibly death. The first step in treatment is figuring out what caused the hydrocephalus. In some cases, things like a bleeding in the brain (intraparenchymal hemorrhage) or tumors might be causing the issue, and surgically removing these could solve the problem. However, if the hydrocephalus continues, doctors usually need to perform surgery to insert a ventricular shunt. This is a device that safely moves the fluid in the brain (known as cerebrospinal fluid or CSF) to another part of the body where it can then be easily absorbed. After treatment, many patients live healthy lives, with few restrictions.

The most common type of shunt is the Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt. This type of shunt drains the brain fluid to the stomach area (peritoneal cavity). This is especially good for children because doctors can leave a large part of the shunt in the stomach area and not need to adjust it as the child grows. The other common type is the ventriculoatrial (VA) shunt. This shunt makes the fluid flow through a vein in the neck (jugular vein) and into the right part of the heart (right atrium). It is mostly used in patients who have problems in the stomach area, have had major stomach surgery, or are very overweight. The third possible option, a lumboperitoneal shunt, is used when a patient has a certain type of elevated pressure in the brain (pseudotumor cerebri). There are also other shunts used in specific situations, like the Torkildsen shunt for a certain type of hydrocephalus.

If shunts are not possible or not preferred, there are alternatives. One approach is an Endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV). This procedure involves creating a hole in a part of the brain which allows the brain fluid to escape. It is often used for a condition known as aqueductal stenosis where there is a narrowing of a passage in the brain through which CSF moves. However, ETV may not work well in very young babies or in patients who have been using shunts for a long time. Another method involves drying up some of the cells that produce the brain fluid, or in some cases, a patient might have repeated lumbar punctures, a procedure where fluid is removed from around the spinal cord, to help with fluid absorption.

If hydrocephalus suddenly gets worse, it is considered a medical emergency. In these situations, if a shunt can’t be placed quickly, doctors may use other ways to get the fluid out of the brain in the meantime. In babies, this could be a ventricular tap through the soft spot on the baby’s skull known as the anterior fontanelle. In adults and children, they might place an external ventricular drain that allows fluid to be taken out of the brain. Another possibility may be a lumbar puncture. For babies born too early (premature infants) with hydrocephalus due to bleeding, they might have a series of taps on the anterior fontanelle. Most patients with a certain kind of brain tumor (posterior fossa tumor) who have hydrocephalus will not need a permanent shunt. A temporary device might be placed to help during surgery and then removed afterwards. Finally, acetazolamide, which is a medication that reduces the amount of brain fluid, can be used for treating hydrocephalus. This is mainly used in pseudotumor cerebri.

What else can Hydrocephalus be?

When examining someone who might have hydrocephalus, a condition which causes a buildup of fluid in the brain, doctors must also consider other conditions that may present similar symptoms. These include:

- Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (often referred to as pseudotumor cerebri), which presents as high pressure in the brain but with no clear cause

- Age-related changes in the brain

- Secondary atrophy, which is brain shrinkage due to conditions like autoimmune diseases, HIV infection, or chemotherapy

- Brainstem gliomas, which are tumors located in the brainstem

- Frontal lobe epilepsy, a form of epilepsy originating from the frontal lobe of the brain

- Frontal lobe syndromes, which are neurological disorders affecting this part of the brain

- Intracranial hemorrhage, or bleeding within the skull

- Migraine headaches

- Primary CNS lymphoma, a rare form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that arises in the brain, eyes, leptomeninges, or spinal cord

- Pituitary tumors, which are tumors located in the pituitary gland at the base of the brain

- Acute subdural hematoma, a condition where blood collects between the skull and the surface of the brain

- Subdural empyema, which is a collection of pus between the brain and the outermost covering of the brain

It’s crucial for the doctors to carefully look at all these possibilities to arrive at an accurate diagnosis.

What to expect with Hydrocephalus

The chances of recovery greatly depend on what is causing the hydrocephalus, a condition where fluid builds up in the brain. For patients with severe intraventricular hemorrhage, which is bleeding into the areas of the brain that contain cerebrospinal fluid, about half may need definitive treatment. In the cases of children who’ve had surgery in the back of their brain (posterior fossa surgery), approximately 20% might need a permanent device, called a shunt, to drain this fluid.

Predicting the success rate of this shunt procedure in instances of normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH), characterized by brain ventricles filled with too much cerebrospinal fluid and causing problems to brain function, is often debated. It’s generally accepted though that if walking problems occur before mental issues, there’s more than a 77% chance of improvement with a shunt.

Another success predictor is the reaction to a single spinal tap or an external lumbar drain. If symptoms improve after withdrawing 40-50 milliliters of cerebrospinal fluid, through a spinal tap or after a drain, it is considered a positive indicator that a shunt will work. Finally, if the brain’s ventricles are still active 48 to 72 hours after a certain diagnostic test called isotopic cisternography, there’s over a 75% likelihood that a shunt will alleviate symptoms.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus, which is an accumulation of fluid in the brain, can cause significant brain damage. The extent of this damage tends to vary. For instance, newborns who are severely affected by hydrocephalus are highly likely to experience brain damage and physical impairments. However, those with less advanced hydrocephalus, who receive proper treatment, have a chance of leading a comparatively healthy life. Further complications may arise with the progression of hydrocephalus, medical treatments, and during surgical procedures.

Possible complications include:

- Changes in vision

- A condition where the temporal lobe of the brain is being pushed out of position (temporal lobe herniation)

- Problems with thinking and understanding (cognitive dysfunction)

- Inability to control bladder (Incontinence)

- Difficulty in walking (Gait problems)

- Imbalance of body salts in the blood (Electrolyte imbalance)

- A condition where the body produces too much acid (Metabolic acidosis)

- Blockage in the shunt (tube that drains the cerebrospinal fluid in hydrocephalus)

- Separation or disconnection of the shunt

- Under drainage or over drainage by the shunt

- A collection of blood outside the brain (Subdural hematoma)

- Accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain (Subdural hygroma)

- Seizures

- Spread of cancer cells outside the nervous system (Extraneural metastases)

- Disintegration of implanted devices (Hardware erosion)

- Inflammation of the peritoneum

- Inguinal hernia

- Punctured abdominal organs

- Intestinal blockage

- Twisting of the intestines (Volvulus)

- Accumulation of fluid in the abdomen (Ascites)

- Life-threatening infection in the blood (Septicemia)

- Infection of the inner layer of the heart (Endocarditis)

- High blood pressure in the arteries of the lungs (Pulmonary hypertension)

- Nerve root disease (Radiculopathy) and inflammation of the arachnoid (a membrane that protects the nerves of the spinal cord) – generally associated with lumboperitoneal shunts

Preventing Hydrocephalus

When you visit the clinic, your doctor will check the tube part of your catheter (either located in your belly or heart) to make sure it is the right length. If needed, they may adjust it. It’s very important that both you and your family know the warning signs of increased pressure in your brain, problems with your catheter, and infections. This is crucial so you can get immediate medical help if necessary.

Regular scheduled check-ups are needed for your doctor to see if there are any issues with your catheter or if there’s a need to adjust your medications. These can include a disconnection in the system, a tube that is too short, or a malfunction in the catheter.

It’s also very important to be cautious not to accidentally hurt the valve and the tubing system (which are placed near the surface of your skin), either by a sudden bump or by scratching your skin constantly. Some patients may need to take antibiotics before undergoing dental work or other procedures that breach the skin, or even some kinds of tests, to help prevent any infections in the catheter.