What is Subdural Hematoma ( shaken baby syndrome, brain bleed)?

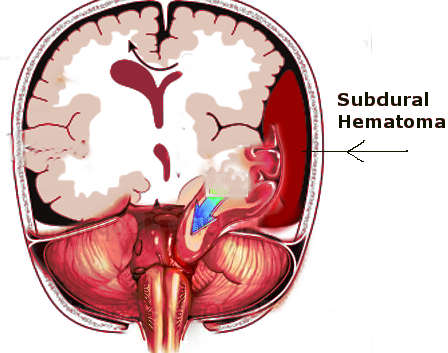

A subdural hematoma, or bleeding under the skin covering the brain, occurs when blood collects under the dura mater, a protective layer below the skull and over the brain. It’s crucial to understand how this condition occurs, which depends on comprehending the brain’s protective layers.

The brain, full of soft nervous tissue and cells that connect these nerves, is prone to injury if it weren’t for the protective layers starting from the scalp to the solid structures of the skull. The brain is safeguarded beneath the skull by the meninges, consisting of three layers.

There are three protective layers between the inside of the skull and the brain:

First, the ‘dura mater,’ a tough layer similar to leather, sticks to the periosteum (a layer that lines the surface of bones) and faces the other protective layer, the ‘arachnoid mater.’ The arachnoid mater is below the dura mater and forms many small projections that penetrate through the dura along with bridging veins. These veins essentially function as one-way channels helping to drain the nervous tissue beneath the final protective layer called the ‘pia mater.’ However, when under direct opposing forces, their thin walls may rupture, causing blood to pool under the dura mater and form a subdural hematoma.

If there’s a larger gap between the dura mater and the brain, like in young children or older people (due to brain shrinkage), the cerebrospinal fluid (a clear fluid in the brain and spinal cord) flows between these veins, taking up more space. This situation can stretch these veins, making them more likely to burst. If there’s a small leakage, it might clear up on its own. But a bigger bleed could lead to more blood layering around the brain, slowly increasing the subdural space and squeezing the brain, leading to herniation, or displacement, of the brain structures.

What Causes Subdural Hematoma ( shaken baby syndrome, brain bleed)?

In children, the main cause of subdural hematoma, a condition where blood collects on the surface of the brain, is typically due to accidents or injuries. Things like blunt force trauma or sudden, shearing (tearing or stretching) injuries are often the culprits. For newborn babies, the majority of subdural hematomas occur due to birthing complications, often as a result of instrument-assisted deliveries.

After the newborn stage, however, and up until age two, unintentional accidents or intentional head injuries are the primary causes of subdural hematomas. The term ‘shaken baby syndrome’ is often used to refer to a subdural hematoma that happens due to intentional shaking of the baby. When a baby is shaken violently, their brain moves back and forth inside their skull. The fragile veins bridging the brain and skull can rupture due to these violent movements, causing a subdural hematoma.

It’s important to note that babies are particularly at risk for shaken baby syndrome because the muscles in their neck aren’t strong enough yet to support their head during such intense movements. Shaken baby syndrome can also cause bleeding in the eyes, which is one of the telltale signs of this condition.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Subdural Hematoma ( shaken baby syndrome, brain bleed)

A subdural hematoma is a type of brain injury often associated with abusive head trauma (AHT) in children. Other injuries that can occur with AHT include epidural hematoma, diffuse axonal injury and parenchymal injury, amongst others. In the case of child abuse, these injuries are all included in the same category.

There’s more data on abusive head trauma in Europe and the United States than in other parts of the world. It is reported that up to 17 out of every 100,000 children per year experience this kind of trauma. However, the rate of subdural hematoma in children under 2 years old is slightly lower, at close to 13 out of every 100,000 children per year.

- The likelihood of a child developing a subdural hematoma is higher in their first year of life, according to a study in South Wales, England.

- In this age group, the incidence is as high as 21 out of every 100,000 children per year.

- Developing countries report similar numbers, but there isn’t a lot of data available.

- No difference has been reported between boys and girls in early-stage subdural hematoma cases.

- However, in teenage years, subdural hematomas resulting from accidental trauma are more common in boys.

Signs and Symptoms of Subdural Hematoma ( shaken baby syndrome, brain bleed)

Assessing a child or an infant with possible head trauma due to abuse often presents challenges. Sometimes, there may be a lack of consistency between the injuries observed and the explanation provided by the caregiver. In such cases, it’s crucial that any suspicion triggers appropriate medical examination and is reported to the relevant authorities.

Infants who had a difficult birth may show symptoms related to trauma. The use of forceps or vacuum devices during birth is a crucial factor to consider. Caregivers may report unusual breathing patterns in the child, pauses in breathing (apnea), changes in behavior, vomiting, unusual movements, or seizures.

Careful examination may reveal changes in the child’s alertness, ranging from irritability to lethargy. If the child has a known history of trauma, external injuries to the scalp may be evident, with possible bleeding underneath the skull. For infants with soft spots on their head still open (fontanels), these spots may feel hard, don’t bounce back when lightly pressed, or may bulge.

Sometimes, there are clear signs of possible abuse on the skin, like bruises or limb abnormalities. However, there might also be cases where no physical injury can be visibly seen during the examination.

Testing for Subdural Hematoma ( shaken baby syndrome, brain bleed)

When a patient is suspected to have a subdural hematoma, which is a collection of blood on the surface of the brain, doctors use various tests and evaluations to pin down the diagnosis. One such test is a complete blood count (CBC), which pays special attention to the levels of hemoglobin and hematocrit. Hemoglobin is a protein in your red blood cells that carries oxygen, while hematocrit is a measure of how much space red blood cells take up in your blood. If there is significant blood loss due to the hematoma, the patient may have anemia, which is a low level of red blood cells.

In long-standing or chronic subdural hematomas, the blood platelet count can go down. This is an indication of a serious condition known as consumptive coagulopathy, which is when the body’s blood clotting processes are over-activated, using up the clotting factors faster than the body can produce them. These changes can be confirmed through other tests, such as measuring the levels of substances like prothrombin and fibrinogen in the blood.

Another condition to look for is high potassium levels in the blood, known as hyperkalemia. This can indicate the breakdown of red blood cells that have leaked into the subdural space.

One of the crucial steps in patient management is to stabilize the patient to reduce the chances of further injury. After stabilization, it’s critical to get better images of the brain and the potential hematoma.

This can be done through a computerized tomography (CT) scan of the head, which uses x-rays to make detailed images of the brain. If there’s time, and the risks of sedation are low, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan could be done. MRI uses magnetic fields to create detailed images of the brain, including the brain stem, and can often show subtle changes that a CT scan might not pick up.

Initial MRI can also help to estimate how old the subdural hematoma is, which could help in determining the best course of treatment.

Treatment Options for Subdural Hematoma ( shaken baby syndrome, brain bleed)

When someone has a subdural hematoma (a collection of blood between the covering of the brain and the brain’s surface), doctors will first ensure the patient can breathe properly and that their blood circulation is stable. Once the patient is stable, the next steps can be planned.

Neurosurgeons or neurologists, doctors who specialize in brain and nervous system disorders, play a crucial part in deciding the subsequent treatment steps. They will assess the severity of the injury and estimate how it will affect the patient both immediately and in the future.

In milder cases, where the subdural hematoma is not increasing in size or pressing on the brain or brain stem, a non-surgical approach may be appropriate. This strategy is usually suitable for subdural hematomas that develop slowly over time or those persisting for a long time.

However, if a subdural hematoma is growing quickly or causing signs of increased pressure inside the skull (such as high blood pressure, slow heart rate, and irregular breathing), emergency surgery might be necessary to relieve the pressure and protect essential brain functions.

While preparing for possible surgery, doctors will start “medical management”. This involves actions such as sedating the patient, temporarily relaxing the patient’s muscles if needed, increasing the patient’s breath rate gently to lower carbon dioxide levels in the blood, ensuring the patient’s oxygen level stays above 95%, raising the patient’s head, and preventing the patient from getting too warm.

Doctors may also use intravenous medications like hypertonic saline or mannitol to decrease the pressure inside the skull. These drugs work by drawing excess fluid out of the brain (osmotic effect) and temporarily improving blood flow in the brain.

What else can Subdural Hematoma ( shaken baby syndrome, brain bleed) be?

Other substances can also gather in the layers of the brain covering, called the meninges, causing it to look like a subdural hematoma, or blood clot on the brain. This means doctors need to closely review a patient’s history and their radiological scans to rule out things like accumulation of pus, known as a subdural abscess. In some cases, places in the brain that are usually filled with a fluid called cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) can appear to be a subdural hematoma due to a naturally decreased brain mass, something that happens in a condition known as hydrocephalus ex vacuo.

What to expect with Subdural Hematoma ( shaken baby syndrome, brain bleed)

The outlook for children who have a subdural hematoma, or bleeding on the brain, can differ greatly. It mainly depends on how severe the injury to the brain is. Unfortunately, many instances of this condition, whether caused by trauma or abuse, go unnoticed. Furthermore, many children end up living with serious neurological problems as a result. These can include seizures and neurodevelopmental delays due to encephalopathy, a term for any broad disease of the brain that alters brain function or structure. These neurological injuries are severe and can have devastating outcomes.