Overview of Central Line Management

Central venous access is a common procedure used for patients who are in the hospital. The process involves placing a central venous catheter, which is a tube inserted into a large vein in the body. This is typically done when regular veins in the arm (peripheral veins) are not suitable for certain medical needs. The reasons for this procedure might include monitoring blood pressure inside the heart, delivering medications that can’t be given through smaller veins, or performing treatments outside the body (extracorporeal therapies).

Getting a central venous catheter comes with certain risks. This is why doctors follow a sterile process while placing and managing the catheter, the goal being to avoid potential issues like skin or bloodstream infections, blood clots in the central vein (central line thrombosis), or mechanical problems with the catheter.

Many hospitals have different ways of looking after catheters based on the resources they have. Yet, a shared idea is about maintaining cleanliness when dealing with the catheters and regularly checking if the catheter is still needed. This is often done through “bundle” packages – a set of required steps for safely putting in and looking after central venous catheters. These usually include checklists and regular learning opportunities to make sure everyone knows the standard of care and can provide it.

Anatomy and Physiology of Central Line Management

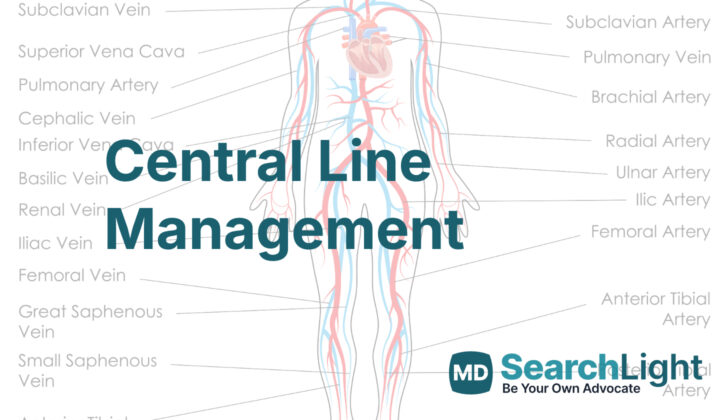

Where a doctor decides to insert a central venous access, a tube placed into a patient’s large vein, depends on the patient’s body structure, health conditions, and the reason for the procedure. The central venous access can be positioned in the internal jugular (vein in the neck), subclavian (vein under the collarbone), or femoral veins (vein in the groin).

Although any of these locations can work, recent findings suggest the subclavian approach is the best choice. This area has the smallest chance of causing an infection. Past research shows that there’s a higher risk of getting an infection from the catheter when it’s inserted in the femoral vein, compared to the other spots.

Why do People Need Central Line Management

If a patient needs to receive fluids or medications via an intravenous (IV) line for a short time and they have suitable veins, doctors usually choose a peripheral venous access. This translates to inserting an IV into one of the smaller peripheral veins, often located on the back of the hand. However, there are some situations where central venous access is required. This involves inserting a special catheter directly into a large, central vein, usually in the chest or neck.

Central venous access is needed if: the medications or fluids can’t be given through smaller peripheral veins; there is a necessity to monitor the patient’s blood pressure in the heart; the patient needs to receive multiple infusions at once or certain infusions that can’t mix; or if the patient requires parenteral nutrition, which is a method of getting nutrition into the body through the veins.

However, using central venous access can increase hospital costs and patient risks, including potentially life-threatening complications. Therefore, healthcare providers should regularly check and follow standard guidelines to reduce these complications. It’s also important to take care of the central venous catheter, especially during use, to avoid infections or other issues- this means cleaning and checking the catheter site whenever it is used or handled.

When a Person Should Avoid Central Line Management

There are certain cases when it might not be advisable to insert a standard central venous catheter, which is a thin tube placed in a large vein to give medication or to collect blood samples.

Although bleeding after the tube is inserted is rare, it can be more of a risk if the person has a major issue with their blood clotting (called severe coagulopathy) before the catheter is placed. If it’s possible, it’s best to fix these clotting or low platelet problems (thrombocytopenia) before inserting the tube. However, this may not always be an option if the patient’s condition is critical.

Other reasons to think twice about inserting a central venous catheter have to do with specific parts of the body. For instance, it is best to avoid areas where other devices already exist within the blood vessels, like permanent tubes for kidney dialysis or pacemaker leads.

Once the tube is in place, there’s no regular routine maintenance that would stop it from being used. In case the tube insertion site gets infected, doesn’t work as well, or there’s a blood infection, ideally we should take out the tube. However, if the tube is key to the patient’s health stability, we can continue using it until we find another appropriate place. Also, in cases where a blood clot forms around the tube, removal of the catheter isn’t always necessary.

Equipment used for Central Line Management

Clean Insertion Methods

* Washing hands properly

* Aseptic technique (this means the set of practices to make sure everything is as germ-free as possible)

* Full body sterile barrier (including a hairnet, mask, gown, sterile gloves, and a full body cover)

* Cleaning the intended insertion site with a germ-killing solution called chlorhexidine

* Securing the catheter (a tube that goes into your body to deliver drugs or drain fluids) with stitches or a clamp

* Placing a clean dressing over the insertion site

Regular Maintenance of the Central Line

* Cleaning with alcohol or germ-killing chlorhexidine wipes

* Using nonsterile nitrile gloves (these are gloves resistant to chemicals and punctures)

* Hand scrub with soap and water or an alcohol-based solution

* Catheter hub locks (used to securely close the catheter when not in use)

Clean Dressing Change Essentials

* Hairnet

* Face mask

* Sterile gloves that fit properly

* Germ-killing chlorhexidine preparation

* Sterile gauze (a type of bandage)

* Biopatch or dressings containing chlorhexidine (used for healing your wound and protecting it from germs)

* A see-through, sterile dressing

Who is needed to perform Central Line Management?

A central venous catheter, which is a type of tube placed into a large vein in your body, is usually inserted by a doctor with special training. Once the catheter is in place, caring for it and making sure it works properly is usually done by trained nurses or other medical staff.

Patients, like those who need to receive antibiotic treatments at home, should not touch or handle the catheter without being properly trained first. It’s important to know how to use and take care of it correctly to prevent any complications.

Preparing for Central Line Management

The hands of healthcare workers can pick up germs from the hospital environment. Therefore, it’s very important for them to regularly clean their hands. This simple act of cleaning hands can help reduce the risk of hospital-acquired and catheter-based infections.

There are standard procedures that healthcare workers follow when placing a central venous catheter, which is a tube that doctors put into a large vein in your neck, chest, or groin to give medications or fluids. When it comes to changing the dressing around the catheter, healthcare workers must use a sterile technique to ensure the area remains free from germs.

How is Central Line Management performed

When a doctor sets up a central venous catheter (a tube we insert into a vein to give fluids or medicines), cleanliness is a top priority. Before putting on sterile gloves, they clean their hands thoroughly with soap and water or alcohol-based scrubs. It’s advisable for them to wear two pairs of gloves. The bottom pair is usually color-coded to make it easy to spot if there’s a tear in the gloves.

Before and during the insertion of the catheter, wearing sterile garb such as gloves, gowns, and using sterile drapes helps prevent the tube from getting contaminated. When preparing your skin for the procedure, your doctor will likely use a 0.5% chlorhexidine solution to kill any germs that could cause an infection. Mild allergies aside, this is a preferable choice over other solutions like povidone-iodine or 70% alcohol. Once the catheter is in place, a sterile dressing is applied to the area where the tube enters the skin, to keep it safe and clean.

After the catheter is set up, it’s checked and handled only when necessary. A daily inspection ensures it is placed and working correctly and also checks for signs of infection like redness or leaking fluid. The dressing over the catheter site should be changed every five to seven days for transparent dressings, and every two days for gauze dressings. However, if the dressing is loose, torn, or dirty, it should be changed right away. Using special dressings impregnated with chlorhexidine hasn’t shown any significant change in infection rates when compared to other common dressings. The use of dressings containing silver for these procedures is not well supported by current research.

Once the dressing is removed, it’s important to clean the site of the catheter to prevent the migration of bacteria. This cleaning is always carried out under sterile conditions, usually using a chlorhexidine solution. After cleaning and drying, a new, sterile dressing is applied and left in place per the institution’s protocol or until the catheter is removed. Repeated removals and applications of dressings can lead to skin irritation and reaction to allergies, so if this happens, the medical team will adjust the protocol accordingly.

Equally important is the cleanliness of the catheter’s connections. Healthcare workers sterilize the injection ports, needleless connectors, and catheter hubs with 70% alcohol or chlorhexidine swabs before using these. It’s also suggested to change the set of equipment used to deliver medication or fluids into the veins (intravenous administration set) every 96 hours. This exchange happens every 24 hours if the set is used to infuse substances containing fats, like total parenteral nutrition (TPN) or propofol, or blood products. Any unused catheter hooks should be kept closed with catheter locks.

The right way of inserting and maintaining a catheter minimizes the chances of complications. To guide healthcare workers, many institutions have central venous catheter bundles, summarizing the key steps including proper hand hygiene, maximal sterile precautions during insertion, skin cleaning with chlorhexidine, avoiding particular body sites for insertion (like the top of the thigh), and removing unnecessary catheters. Regardless, the level of care may vary depending on available resources, inducing variability in infection rates.

Possible Complications of Central Line Management

There are several problems that a patient may encounter when having a central venous catheter placed. This is a tube inserted into a large vein in the neck, chest, or groin, to give medication or draw blood. These problems can occur both during the placement and afterwards. The risk of these complications increases if the procedure is carried out without the help of ultrasound imaging. This could lead to more attempts being needed to insert the catheter and a higher chance of accidentally inserting it into an artery or nearby structures by mistake.

One of these complications is accidental puncture of an artery. This could cause a blood clot or a pseudoaneurysm (false aneurysm), where blood leaks into the surrounding tissues from the artery. This can compress the tissues around it, split up the layers of the artery wall (dissection), and even cause an abnormal connection to form between the artery and a vein.

Another possible complication during the placement of a central venous catheter is the onset of abnormal heart rhythms, or arrhythmias. These can occur if the catheter or guide wire enters the heart, or if it’s placed incorrectly.

After the catheter has been inserted, the most common problem is infection. If a patient with a catheter starts to show signs of fever, redness around the area where the catheter was inserted, sudden swelling, discharge of pus, a rise in white blood cell count, or instability in blood circulation, they should be checked for infection. The catheter might be the cause of infection in such cases and it may need to be removed.

Another common problem after the catheter placement is the blockage or occlusion of the catheter. This can happen if the catheter slips out of place, if a blood clot forms in the catheter, if the medication being given through the catheter solidifies, or if there are physical obstructions in the catheter. For this reason, catheters need regular inspections.

Sometimes, a blood clot (thrombosis) can form in the catheter. This can cause complications and if not managed properly, can even lead to death. Most of these catheter-related blood clots occur in the upper extremities (arms). The blood clot itself can potentially become a source of infection, or it might grow. There may not necessarily be noticeable symptoms for every patient with catheter-related blood clotting. Patients with blood clots in their catheters are generally not recommended to have the catheter removed as a routine practice; instead, anticoagulation therapy, which is a treatment that prevents blood clots from forming, is often used to manage this condition.

The catheter can also get blocked if it is bent or twisted at any point, or if it is put under physical pressure from a stitch or an external source. In cases where a blood clot is suspected after trying and ruling out other causes, medications that dissolve blood clots, called thrombolytic agents such as alteplase, can be used. To prevent blockages or blood clots from forming, the catheter should be regularly flushed out with either heparin or normal saline. Research has shown no significant difference between the effectiveness of using either heparin or a saline solution for these regular cleanings. It is also important to flush the catheter with saline before and after administering medication through it.

What Else Should I Know About Central Line Management?

Managing a central venous catheter, a tube placed into a large vein, is done with the aim to reduce the chances of infections, which are the most common issues of having one. Other complications like abscesses (pus collection inside body tissue), cellulitis (a common skin infection), and bacteremia (bacteria present in the blood) can also occur. These complications can cause patient’s health to deteriorate, lead to more extended use of antibiotics, and increase the length of the hospital stay along with the overall medical costs. Regular cleaning and maintenance of the catheter is crucial to prevent such complications. However, deciding whether to keep the catheter is equally important. If there are concerns of sepsis (severe reaction by your body to an infection) or continuous bacteremia, despite using the appropriate antibiotics for over 72 hours, the catheter should be removed.