Overview of Mitral Valve Repair

When the mitral valve in the heart starts to change and wear down, a surgical repair is generally the best option. However, how well a patient does after the repair can depend on many things. This includes their health before the operation, how severe their mitral valve issue is, what type of repair they get, and how skilled and experienced their surgeon and medical center are. If the repair is done quickly, the operation usually has a low risk, and the person’s life expectancy is close to someone their age and gender who doesn’t have this heart issue. For people in high risk categories, the choice between surgery, less invasive procedures, and conservative treatment can be tough. The best choice usually depends on any other health problems they have and the skills of their surgeon. Also, repairing the mitral valve tends to be better than replacing it but personal factors should be considered.

Important to note though, nearly half of the people with serious mitral valve problems can’t get surgery because of their age or other health issues.

About 2% to 3% of adults in the United States have a mitral valve disease. If a person with mitral valve disease starts to show symptoms of mitral regurgitation (where the valve doesn’t close all the way and allows blood to flow backwards), it can be very serious, with the yearly likelihood of death up to 34%. Mitral stenosis, where the valve doesn’t open fully, usually due to a disease caused by a previous strep infection, is often treated by a less invasive procedure called percutaneous mitral balloon commissurotomy or valve replacement. Repairing the valve usually isn’t an option for people with this type of mitral valve disease.

One can have mitral regurgitation for different reasons. It is classified as primary or secondary depending on the exact location of the issue. Severe cases, regardless of the category, are generally treated with surgery. However, as technology advances, treatments that are less invasive are also becoming more common. Valve replacement might be needed for cases caused by a rupture in the small muscles that allow the valve to work, wear and tear, lack of blood supply, or if a previous valve repair didn’t work.

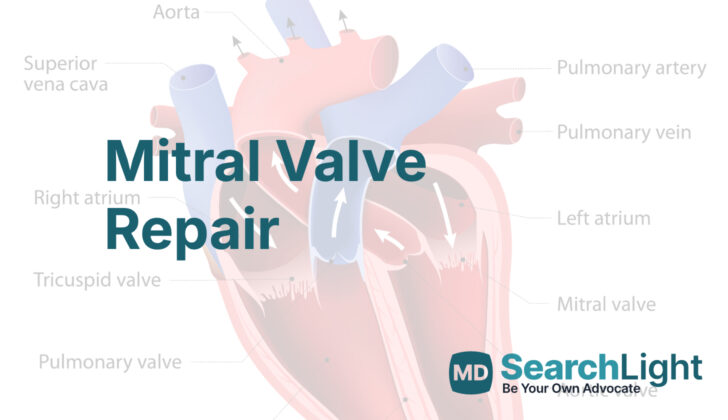

Anatomy and Physiology of Mitral Valve Repair

The mitral valve is a complex part of the heart with many parts, including a ring-like structure called an annulus, two flaps called leaflets, different types of tiny cords called chordae tendinae, and two small muscles called papillary muscles. The mitral annulus, shaped like a “D”, can be found where the left atrium and left ventricle of the heart meet the mitral leaflets. The mitral annulus helps to supply blood to the mitral leaflets alongside other parts of the heart like the left circumflex artery and the coronary sinus.

The mitral valve annulus is similar to the aortic valve, another part of the heart, and is more prone to stretching or dilatation at its weakest point – the location where it inserts on the back leaflet. The two mitral valve leaflets differ in size and meet at areas known as commissures. Each leaflet has sections known as scallops. The front leaflet takes up a larger area of the valve and a smaller part of the annulus, while the back leaflet covers more of the annulus circumference. As the back leaflet is attached to the free wall of the ventricle, it is more susceptible to prolapse, or falling out of place, due to the repetitive pressure from the heart pumping.

The chordae tendinae, tiny fibres that connect the mitral leaflets to the papillary muscles, come in three types based on where they attach. The papillary muscles also have locations and receive blood from specific arteries. These different components all work together to ensure blood flows properly from the left atrium to the left ventricle. In cases of Mitral Regurgitation (MR), a condition where the valve does not close properly and the blood flows back to the heart, the left ventricle may become thin, stretched, and unable to function properly, leading to an increased risk of irregular heart rhythms or arrhythmias.

Some irregularities of the mitral valve are increasingly seen as indicators of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM), a disease where the heart muscle becomes abnormally thick. These irregularities include movement of the mitral valve, elongated mitral leaflets, and anomalies of papillary muscles. A study found that in patients with HCM, the length of the mitral leaflets was significantly longer and the papillary muscles often presented anomalies. Similarly, there were common abnormalities like degenerative changes, myxomatous degeneration, and leaflet restriction in those with HCM.

The normal functioning of the mitral valve can be disrupted leading to significant changes in how blood flows in the heart in conditions like Mitral Stenosis and Mitral Regurgitation. Mitral Stenosis (MS) is the narrowing of the mitral valve, which restricts the flow of blood from the left atrium to the left ventricle. Rheumatic heart disease, a disease that can occur after strep throat or scarlet fever, is a common cause of MS. Other causes of MS include radiation-induced inflammation of the valve, systemic inflammatory disorders, tumour-like growths, infections, and calcium build-up in the mitral annulus observed in older patients or those with advanced kidney disease. Progressive MS can lead to increased pressure on the left atrium, resulting in increased chances of blood clots, arrhythmias, lung issues, and right ventricular failure.

Why do People Need Mitral Valve Repair

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) have set certain guidelines to manage two heart conditions: mitral stenosis (MS), which is a narrowing of the mitral valve, and mitral regurgitation (MR), where the valve doesn’t close properly, allowing blood to leak backwards. These are often treated with mitral valve repair.

For mitral stenosis, the treatment options aren’t as common as MR, and mostly involve a non-surgical treatment called percutaneous balloon commissurotomy (PMBC). However, mitral valve repair is considered in situations where PMBC isn’t possible. The ACC/AHA suggests treating MS in a few different situations:

- If a patient with severe MS is showing symptoms and can’t undergo PMBC because of the structure of their valve or other complications, they should be considered for mitral valve repair.

- If a patient with severe MS starts to experience irregular heartbeats or continues to have blockages in their vessels, valve repair or replacement may be considered.

- If a patient with severe MS starts to develop high blood pressure in the lungs and can’t undergo PMBC, surgery might be recommended.

- If a patient with moderate MS is showing symptoms and needs another heart surgery such as a bypass, mitral valve repair could be considered.

For mitral regurgitation, valve repair is often preferred. The ACC/AHA suggests early treatment in some cases to avoid long-term problems:

- If a patient with severe primary MR is showing symptoms but the heart is still working relatively well, surgical repair of the mitral valve is advised.

- If a patient with severe primary MR doesn’t have symptoms but the heart isn’t working as well, early surgical repair is strongly recommended to prevent further heart damage and heart failure.

- If a patient with severe primary MR has an irregular heartbeat or high blood pressure in their lungs but the heart is still functioning well, mitral valve repair should be considered.

- If a patient with severe primary MR doesn’t have symptoms but the heart is working well and the repair is likely to be successful and long-lasting, then early mitral valve repair could be considered.

- If a patient with severe secondary MR has heart failure and is undergoing another heart surgery, mitral valve repair may be considered. However, depending on the cause and the function of the heart, replacement of the mitral valve may be more suitable.

- If a patient with moderate secondary MR is having surgery for another heart issue, mitral valve replacement should be considered to address the MR and improve the patient’s long-term outcomes.

When a Person Should Avoid Mitral Valve Repair

If someone has a severe problem with their mitral valve, a heart valve that controls blood flow, they need to be checked by a heart surgeon who specializes in operating on this valve. This check-up is to see if they’re a good candidate for surgery, and it involves looking at their heart arteries, any other medical conditions they might have, and their past surgical experiences.

Heart surgeons use a risk calculator from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons to decide how likely it is that the patient may die or have serious problems from surgery. Patients with hardened aortic valves (calcified), poor functioning of a specific part of the heart (RV dysfunction), or severe calcification on the ring part of the mitral valve, are considered to have somewhat higher risks when it comes to repairing the mitral valve.

Also, if the function of the lower left chamber of the heart (LV) is impaired, surgery might not be a good option. That’s because the repaired valve will work too well, putting extra stress on this part of the heart, which could overestimate how well the LV is truly functioning.

Patients suffering from severe emphysema, a lung condition that can make it hard to breathe, and other lung and heart conditions have a higher risk of complications and are also seen as having a high risk when it comes to surgery. This is especially the case, when the problems have been going on for a long time causing high blood pressure in the lungs.

Equipment used for Mitral Valve Repair

Mitral valve repair is a heart surgery that needs a machine called a cardiopulmonary bypass to do the work of the heart and lungs during the procedure. Almost all the time, your heart will be completely stopped for the operation. The doctors will use standard tools that are needed for open heart surgery.

During the surgery, another important tool that the doctors will use is a procedure called transesophageal echocardiography. This is a special type of ultrasound test that takes pictures of your heart through your esophagus (the tube that connects your throat to your stomach) to help guide the surgery and assess the function of your heart.

Who is needed to perform Mitral Valve Repair?

Fixing the mitral valve, a valve in your heart, calls for a specialized team of heart experts. This team should include a cardiac surgeon, who is a doctor highly skilled in performing heart surgeries, particularly those involving the mitral valve; a cardiac anesthesiologist, who helps you safely sleep during the operation; and a perfusionist, who operates a machine that does the work of your heart and lungs during the surgery. Other team members include a surgical assistant, who helps the surgeon; a surgical nurse or technician, who prepares, maintains, and sterilizes surgical equipment and assists the medical team; and a circulating or operating room nurse, who coordinates the surgery room and assists the team.

After the surgery, your care will be handled by a critical care intensivist, a doctor who specializes in the care of patients with critical illnesses. A cardiologist, a doctor who specializes in heart diseases, will also oversee your care. A physical therapist will guide you through exercises to help your recovery, and a social worker will connect you with any resources and support you need. Various levels of nursing staff will also help you throughout the recovery, providing round-the-clock care and monitoring your progress.

Preparing for Mitral Valve Repair

Before undergoing heart surgery, doctors will thoroughly assess the patient’s overall health and the potential risks involved with the procedure. This involves getting a detailed health history, physically examining the patient, reviewing any previous medical tests, and getting advice from other medical specialists if needed. Key risk factors for heart surgery include issues such as reduced blood flow to the heart, heart failure, and hardened or blocked arteries in the neck or near the heart. Understanding the cause of heart failure is crucial to deciding the best way to manage the patient’s body functions during and after surgery.

Based on these factors, patients will be placed into low, medium, or high risk categories. Low-risk patients have chest pain (angina) but no recent heart attack, and their surgery is planned ahead of time. Medium risk patients may have recently had a heart attack but are otherwise stable. They usually need hospital care and medication to prevent blood clots. High-risk patients are unstable after a recent heart attack and have a much elevated chance of complications and death. Patients with heart failure need extra tests to look at how well the heart’s pumping chambers (ventricles) are working. The plan for giving them anesthesia during surgery will need to consider things like how to monitor their heart, which medications to use, and whether any extra support is needed for the heart.

If you have blocked arteries in the neck or near the heart, you have a higher risk of stroke during surgery. Other health conditions that need to be taken into account include diabetes, high blood pressure, previous strokes, problems with blood flow in your legs or arms, and lung diseases from smoking. Stroke risk can be lowered by taking medications like aspirin, beta-blockers and statins ahead of surgery. Some patients may also need to see a vascular surgeon before the operation. Sometimes, during heart surgery, bits of the hardened plaque inside the artery can break off, which can increase the chances of having a stroke.

Certain risk factors that cannot be changed include being a woman, being older, certain heart conditions, having kidney issues, a previous temporary loss of blood flow to the brain (transient ischemic attack), anemia (low red blood cell count), and a history of smoking. Existing kidney problems can worsen suddenly in 1-2% of patients, which can increase the chance of death. These individuals should avoid medications that can harm the kidneys, and should make sure they are well hydrated. Low heart rate or low blood pressure should be treated quickly. Anemia, which is common in people having heart surgery, can make blood transfusions more likely. If a patient has diabetes, it’s important to avoid very low or very high blood sugar levels to help prevent problems during or after surgery. Those with high blood pressure should continue to take their normal blood pressure medications up to the day of surgery, except for certain types which are usually stopped.

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a lung disease usually caused by smoking, should have their lung function as optimal as it can be before the surgery. This usually involves counseling those who smoke to quit before the operation. Making sure the patient is eating well before surgery and getting the right support after surgery can help increase the chances of success in older patients. In planned surgeries, the longer the surgeon has to stop the flow of blood in the aorta or keep the patient on a heart-lung machine, the higher the risk is. The experience of the surgeon and the hospital also plays a role in the chances of survival.

If you’re having surgery because of issues with your heart valves, medications like diuretics and beta-blockers can help manage your symptoms up to the point of surgery. Patients with a heart rhythm issue called atrial fibrillation usually need to take warfarin, a blood thinner, before surgery. Vasodilators are often used to decrease the resistance in your arteries to improve your heart’s pumping capability, reduce leaky blood flow through the heart valve, but maintaining this improvement can be challenging.

How is Mitral Valve Repair performed

The mitral valve repair procedure exists to correct issues with your heart valve and improve the flow of blood. Over time, advancements in surgical techniques and less invasive methods have enhanced our ability to fix these issues, keeping your valve intact whenever possible. The following discussion provides an overview of the classical and modern methods used to accomplish mitral valve repair, aiming for the best possible results for patients.

Standard Mitral Valve Repair

The ‘standard’ mitral valve repair procedure is performed using a machine to take over heart and lung functions (cardiopulmonary bypass) and a process to stop heart activities (ischemic arrest). This procedure can be approached in different ways, such as using the chest bone as an entry point (median sternotomy), entry from the right side of the chest wall (right thoracotomy), or with the aid of a robot. The main aim is to make sure your valve can close properly and not allow blood to flow backward, reduce the size of the valve opening if it’s too large, and prevent blood flow from pushing the valve into the left upper chamber of your heart.

This traditional method is particularly essential if you need additional surgeries like a bypass for heart arteries, procedures dealing with the main artery carrying blood from the heart (ascending aorta), or when more than one valve needs to be handled.

Alternatively, the Carpentier and Lawrie Techniques are techniques developed for mitral valve repair. Carpentier’s technique uses a process of removing an area of bulging valve tissue and applying a rigid ring to correct a dilated valve opening. Lawrie’s technique, on the other hand, keeps the valve and its chords intact and uses an artificial fabric chord to correct valve defects. In most cases, these methods provide stable long-term outcomes.

Percutaneous Mitral Balloon Commissurotomy

The Percutaneous Mitral Balloon Commissurotomy (PMBC) approach is a less invasive method that has been proven safe and effective when the valve has favorable features. In a PMBC, a small tube (catheter) with one or more balloons is advanced across the valve and inflated to open the blocked valve structures. Factors that can determine how well this approach works include the patient’s age, the classification of their heart condition, and whether they have irregular heartbeat or not.

Commissurotomy

Commissurotomy is the preferred surgical option for a narrowed mitral valve caused by a disease that affects the heart valves (rheumatic MS) when the valve anatomy allows. This procedure can be done either as a closed or open commissurotomy. However, if the valve has significantly thickened or there’s fibrosis beneath the valve, replacing the valve might be the best option. An additional surgical procedure, such as treating an irregular heartbeat (atrial fibrillation ablation) and tricuspid valve repair, is strongly recommended together with the mitral valve replacement.

Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery

Less invasive surgeries, known as minimally invasive mitral valve surgeries (MIMVS), have been developed, dividing into two groups: partial sternotomy and right thoracotomy. These approaches have proven to yield equivalent results to conventional surgeries in terms of stroke occurrence, mortality rates, and the durability of the repair while reducing trauma. Advantages include less blood loss, a quicker return to regular activities, and most times, lower hospital costs. This less invasive method is becoming more widely adopted, and some use robotic assistance, further reducing the invasiveness of the procedure.

Possible Complications of Mitral Valve Repair

Sometimes, after a surgery to repair the mitral valve in the heart (a procedure known as mitral valve repair), the valve might malfunction again, which is the most common complication. This malfunction is known as Recurrent Mitral Regurgitation (MR). Doctors check for MR by measuring heart pressures, which give insight into what’s happening inside the heart. The v wave, a measure of these pressures, can provide critical clues to any condition that affects the atrium of the heart. An enlarged v wave often suggests MR, and extremely large v waves can occur in emergencies like a broken heart string (ruptured chordae tendineae). Two times or more of average heart pressure indicates severe MR.

In some circumstances, such as in a severe leak around the mitral valve, high v waves can lead to lung high blood pressure (pulmonary hypertension) and one side of the heart failing. Fixing the leak usually leads to a quick reduction in the size of the v wave and improvement in heart function.

After the mitral valve is repaired, doctors need to closely examine it using a special heart scan (TransEsophageal Echocardiogram or TEE). If the scan shows that the valve still leaks to some extent, doctors must decide whether to try to fix it again or replace it entirely. This is particularly important in patients whose heart muscle has reduced function, as they may not handle an extended repeat operation period.

Although doctors always aim for a long-lasting fix to the mitral valve, this sometimes may not be possible. In some studies, only half of the patients treated remain free of MR 7 years post-repair. Side by side comparison of valve repair and replacement in older patients show similar results. However, overall, people having mitral valve repairs had fewer deaths after surgery than those having their valves replaced.

Following successful mitral valve repair, patients with lung hypertension and a type of irregular heart rhythm (atrial fibrillation) may fare worse in the long run. Some patients may develop atrial fibrillation after surgery, particularly those with expanded left atrium, leading to more deaths. Today, an increasing number of doctors rectify this issue by performing a surgery to correct atrial fibrillation during mitral valve repair.

If the repaired valve moves into the blood outflow tract in the heart during contractions, this could cause MR or obstruction. If this is noticed after repair, doctors will work to optimize filling of the heart, pacing the heart to improve co-ordination, and reducing excess contraction of the heart muscle. Medications such as beta blockers may also be helpful in managing this condition.

Surgery to the mitral valve carries a small risk of injuring the artery running close to the valve area (circumflex artery), especially in cases of a particular disease (Barlow disease) where the valve leaflets are exceedingly mobile and the ring of the valve is widened. This risk is slightly higher when you repair instead of replacing the mitral valve, and remains the same even with minimally invasive procedures. If detected during surgery, doctors will use immediate surgical procedures to restore blood flow, while if detected after the surgery, a procedure (Percutaneous Coronary Intervention or PCI) may be used to open narrowed or blocked blood vessels that supply blood to the heart. If there are complications while attempting PCI, surgical intervention is considered.

A rare but severe complication that can happen after mitral valve replacement surgery is a break in the continuity between the heart’s upper and lower chambers (AV groove disruption). This may be due to surgical techniques or an injury from extensive surgery. It may carry a high risk of death, and repair is generally challenging. Older age can increase the risk of such complications. Maintaining a part of the posterior leaflet and basal chordae can reduce the risk of AV groove rupture. However, if a complete rupture happens, it poses significant risks if not properly dealt with and may require surgery.

What Else Should I Know About Mitral Valve Repair?

As we get older, it’s common to encounter issues with our heart’s mitral valve, which helps control blood flow through the heart. This condition, known as mitral valve regurgitation (MR), can lead to heart damage if it’s not treated properly. The best way to handle this is through a procedure known as a mitral valve repair.

Current American and European guidelines recommend this surgery for patients with MR, especially if they’re showing signs of left ventricular (LV) dysfunction. The left ventricle is the chamber in your heart that pumps out the blood to the rest of your body. Doctors classify it as “dysfunctional” if it’s not working well, for instance when the ejection fraction (LVEF, a measure of how much blood the left ventricle pumps out with each contraction) is below 60%, or when the LV has a diameter greater than 40 mm when it’s fully contracted.

Surgeons often advise MR patients to undergo this operation even if they’re not showing symptoms, particularly if they evidence LV dysfunction. Both American and European guidelines favor mitral valve repair over replacement. Additionally, they recommend the operation should take place before LV dysfunction occurs.

Having MR can cause your heart to work harder than it should, which can lead to structural and functional issues with the heart. This ultimately could cause heart failure. Therefore, it is crucial to address MR promptly to ensure your heart keeps functioning well. There are now minimally invasive methods and transcatheter techniques available, which can repair the mitral valve. These procedures are particularly useful for high-risk individuals who might not be suitable for traditional open-heart surgery.