Overview of Chest Tube

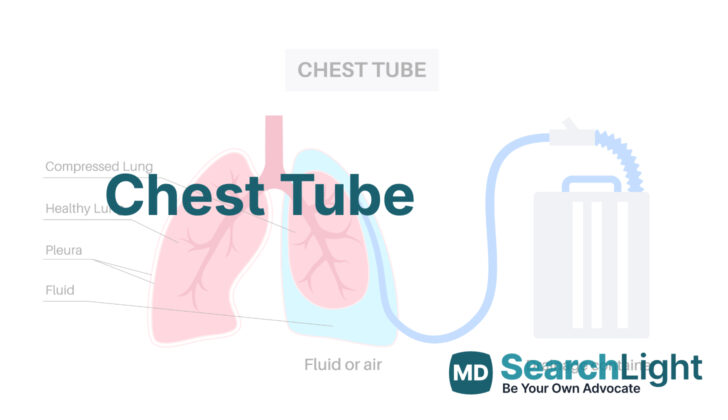

A chest tube, also known as a thoracostomy tube, is a flexible pipe, that can be put in between the ribs into the space around the lungs, called the pleural space. These tubes are usually made from flexible materials like PVC or silicone. They can come in various sizes from very small (6 French) to larger ones (40 French). Most tubes have holes along the side of the end that gets inserted into the body, and a special stripe that shows up on X-rays.

Once the tube is in place, the far end is attached to a system, called a pleura-evac, that helps to manage fluid and air. This system has three separate chambers: the suction chamber, the water seal chamber, and the collection chamber. The water seal chamber acts like a one-way valve, letting air out due to gravity, but preventing it from going back into the chest.

The picture shows a typical example of a chest tube. This tube plays a crucial role in treating conditions involving an excess build-up of air or fluid around the lungs.

Why do People Need Chest Tube

Doctors use a special tool called a chest tube to help the lungs expand normally by creating a pulling or ‘negative’ pressure in the chest cavity. This tube essentially helps to get rid of unwanted things in the chest area, such as air, which is the case in a condition called pneumothorax. It can also help remove blood (hemothorax), fluid (in the case of pleural effusion or hydrothorax), a certain type of fluid called chyle (in chylothorax), or pus (in empyema).

While the chest tube has other uses, these are less common and not usually needed. For a specific case called ‘tension pneumothorax’, where there’s a dangerous amount of pressure in the chest from trapped air, the medical professionals would firstly use a needle to reduce the pressure, and then a chest tube would be promptly placed once the patient is stable after the decompression step.

When a Person Should Avoid Chest Tube

Certain conditions might make it less safe for someone to have a chest tube placed inside them. These conditions can include:

If the person has had surgery on their lungs before, or if they have lung disease or injury, it may have caused pulmonary adhesions – which are bands of scar tissue joining surfaces of the lung. This could make the procedure to insert a chest tube more complicated.

A person might also be not recommended for this procedure if they have a ‘coagulopathy’ which is a problem with their blood making it hard to stop bleeding.

Lastly, people who have diaphragmatic hernias, which is a condition when part of your stomach pushes into your chest through a weakness in your diaphragm, might also not be suitable for a chest tube placement.

How is Chest Tube performed

Placement: A chest tube is generally inserted between the mid to front side of the armpit in the fourth or fifth space between the ribs, in order to avoid damaging the bundle of artery, vein and nerve (intercostal bundle) that runs between each rib. The fourth space between the ribs is usually at the level of the nipple for men or the underside of the breast fold for women. It’s better to position this tube a little higher than the rib space to create a ‘flap’ of soft tissue. This ‘flap’ is useful because, once the tube is removed, it helps to stop air from getting back into the chest and triggering a recurrence of pneumothorax (a collapsed lung).

In some cases, ultrasound or CT scans might be used to help locate the best spot for the chest tube. These imaging techniques are particularly helpful when dealing with patients having a history of infection or surgery because these conditions make them more prone to scarring. It’s also a good idea to administer preventative antibiotics prior to the tube’s placement in surgical or trauma scenarios. After the tube has been placed, it’s standard to do a follow-up chest X-ray to confirm that the chest tube is where it should be. Usually, for pneumothorax, a straight tube is directed towards the top or ‘apex’ of the lung. For hemothorax (blood in the pleural cavity) or pleural effusion (excess fluid between the layers of the pleura), a straight tube is usually positioned towards the back and top of the lung and/or a right-angled tube might be placed at the base of the lung and diaphragm.

Removal: When you or your caregiver remove the chest tube, it’s important not to do it while you’re breathing in, as this can cause a pressure difference within your chest. That can lead to air getting into the space around your lungs, which might cause a persistent or recurrent pneumothorax even after the tube has been removed. Fortunately, there are a few techniques to avoid this. One method is to coordinate the removal of the tube with your breathing pattern. Another method involves you holding your breath or pretending to blow up a balloon. Applying an airtight dressing or bandage using materials like Vaseline or Xeroform gauze is advisable, or a ‘U-stitch’ can be inserted around the incision site which is then pulled tight when the tube is removed.

Possible Complications of Chest Tube

Chest tubes are used to treat several medical conditions, but they can sometimes cause complications. These complications include:

* Bleeding: Blood could start leaking out of the area where the chest tube was put in.

* Superficial site infection: The surface of the skin where the chest tube was inserted might get infected.

* Deep organ space infection (empyema): This is a more serious infection inside your body, potentially affecting your lungs or other chest organs.

* Dislodgement of the tube: The chest tube might moved out of the correct position.

* Clogging of the tube: The chest tube is used to drain fluids from your body; if it gets clogged, it won’t work properly.

* Re-expansion pulmonary edema: This is a condition that might occur when a collapsed lung is reinflated. It happens rarely, but it can cause fluid to build up in the lungs.

* Injury to intraabdominal organs such as the spleen or liver: These organs are located in the abdomen, and there’s a small risk that they could be accidentally injured when the chest tube is inserted.

* Injury to the diaphragm: The diaphragm is the large muscle at the base of the chest that helps you breathe.

* Injury to intrathoracic organs, such as the heart or thoracic aorta: These are organs located within the chest or thorax, and there’s a possibility they could be injured during chest tube insertion.

What Else Should I Know About Chest Tube?

A chest tube is a device that can save lives by removing unwanted substances like air, blood, and infectious fluids from the chest.

Chest Tube Care

The best way to take care of a chest tube isn’t clearly defined or agreed upon by medical experts, and can vary depending on the doctor’s training and experience. This is more of an art than a science. It’s also influenced by the reason the chest tube was put in. The main idea behind managing a chest tube is to get the two layers of tissue lining the chest (the visceral and parietal pleura) close together so they can adhere to each other again. The chest tube can be managed in three ways: by applying suction, sealing it with water, or clamping it.

Sometimes, new leaks of air can occur around the chest tube. When this happens, doctors need to check the chest tube, the tube connecting it to the suction device, the suction device itself, and the wound where the tube enters the patient’s body. It could be that the tube has become disconnected or that it has slipped out of the chest. Conditions like steroid use, damaged lungs, extensive scar tissue from previous surgeries, and significant chest trauma can make these air leaks more likely.

Normally, suction is used when a chest tube is first put in, except for certain types of chest surgeries. Once the chest x-ray shows no air leak or air outside the lungs, the tube can be sealed with water. Tubes put in to create scarring between the tissue layers lining the chest (pleurodesis) or remove thickened tissue (decortication) may need to stay on suction longer. The chest tube can be taken out when the air leak has stopped, there’s no blood coming out, the amount of fluid coming out is less than 150 to 400 cc over 24 hours, the patient is off the breathing machine, or if there is no or a mild amount of air outside the lung on chest x-ray. If the air leak does not stop with this strategy, a chest surgery specialist needs to be called. If the tube was put in because of a large amount of blood in the chest from trauma, and there’s initially more than 1500 cc of blood coming out or an average of 200 cc/hr over 4 hours, then the patient may need to have chest surgery.

If there’s a large amount of blood in the chest that remains after trauma and it doesn’t improve with chest tube care, then there are several options. Currently, the trend is to perform a minimally invasive procedure known as video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) early on. Another option includes inserting a second chest tube or injecting a drug called tPA into the tube if the blood in the chest is thought to have clotted. Some doctors who specialize in trauma or chest surgery are now performing VATS immediately if there’s blood remaining in the chest after the first chest tube is put in.

Extra Tips

Small chest tubes (like Wayne catheters) are meant to be used for air outside the lungs rather than for blood or fluid in the chest because of the risk of the tube becoming blocked. In adults, larger chest tubes, usually 28 French or bigger, are necessary for draining blood or pus.