Overview of Percutaneous Central Catheter

Being able to access veins in a patient is a fundamental and important part of many medical treatments both in the hospital and outpatient clinics. This is particularly necessary for seriously ill patients who often need frequent blood tests, specific medications, quick fluid replacements, long-term antibiotic use and various other needs. The medical team may access veins through several methods including standard intravenous (IV) lines, midline peripheral catheters, and central venous catheters (CVCs).

A Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter (or PICC) is a particular type of central venous catheter. It’s a tube that’s 50 cm to 60 cm long with one to three channels, which is inserted in a vein in the arm and extends to the chest. PICCs are used when someone needs to have access to their veins over a somewhat lengthy period, ranging from a few weeks to up to six months.

Anatomy and Physiology of Percutaneous Central Catheter

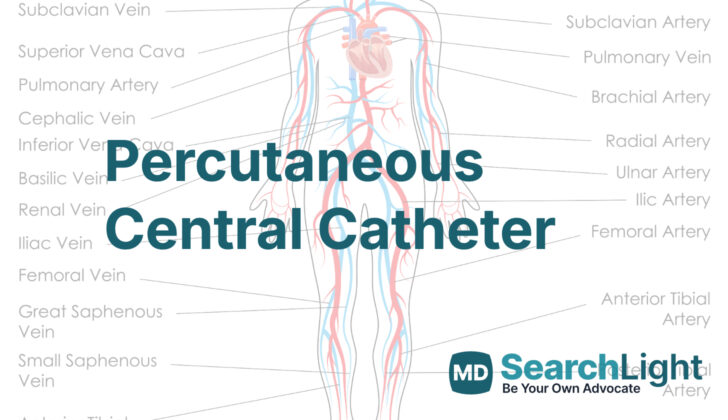

A central catheter is a device used to access the veins in your body, ending in a large vein near the heart called the superior vena cava (SVC) or right atrium (RA). There are two kinds of these devices – one that’s inserted at the center of the body (CICC) and one that’s inserted from the side of your body (PICC). PICCs enter your body through the veins in your arm, such as the basilic, brachial, cephalic, or middle cubital vein.

The preferred vein for inserting a PICC is the right basilic vein. It’s chosen because it’s large, near the surface of the skin and has the most direct route to the SVC. It goes through the axillary vein in the armpit, then the subclavian vein near the collarbone, before settling in the SVC. The basilic vein is also favourable because it has fewer valves, dilutes the blood better, and requires a less steep angle for the catheter to be inserted.

The median cubital vein, which is prominent in the fold of the elbow and goes directly to the basilic vein, is the second-best choice for a PICC. However, because of its location in the elbow joint, frequent bending of the arm could increase the risk of complications such as inflammation of the vein walls.

The cephalic vein in the upper arm could also be used for PICC placement, but it’s not an optimal choice. It’s smaller than the basilic vein and doesn’t provide a straight path for the catheter. This could make the device harder to advance and increase the risk of inflammation.

The brachial vein is another option. Despite being larger, it’s still smaller and deeper than the basilic vein. It runs really close to the brachial artery and a key nerve in the arm, which means doctors might have to use an ultrasound to guide the device into place safely.

Why do People Need Percutaneous Central Catheter

A Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter (PICC) is a safe and effective way of getting access to your veins. It’s used especially when you need to have something put into your veins over several weeks or months. This is because PICCs are less likely to cause an infection than some other methods. What’s more, they can be used whether you’re staying in the hospital or going home.

Here are some situations when a PICC might be used:

* If it’s hard to find a vein in your arm for an injection

* If you need to be given medicine continuously through a vein for a long time, like antibiotics or antifungal meds

* If you need to be given drugs that can irritate your veins, like some heart meds or chemotherapy drugs

* If you need to receive a high amount of nutrition directly into your veins (this is called total parenteral nutrition)

* If you need to receive a lot of blood infusions

* If you need frequent blood tests

* If you have a condition that makes your blood clot too much or too little (this is called thrombocytopenia)

* If you have unusual structures in your chest or neck that make it hard to put in a central catheter

* If you need to receive a lot of a drug quickly

In all these situations, a PICC makes it easier and safer for you to get the treatment you need.

When a Person Should Avoid Percutaneous Central Catheter

Sometimes, there might be reasons why a central venous catheterization isn’t possible. This is a procedure where a tube is placed into a large vein in your neck, chest, or groin. It’s often used in serious circumstances when other treatments are required to save a person’s life. But there are situations when this procedure is inadvisable. These situations are as follows:

- If the area where the tube needs to be inserted has a burn, skin infection, has been injured in an accident, has had radiation treatment, or if there’s a history of blood clots.

- If a person has an active bacterial infection in their blood.

- If a person has serious long-term kidney disease (because the veins might be needed later to place a dialysis catheter for kidney treatment).

- If the veins in the person’s arm are too small for the procedure – this usually applies to veins smaller than 3mm to 4mm in diameter.

- If a person has had surgery to remove their breast and lymph nodes (the lymph system is damaged and can’t properly drain fluids).

- If a person needs crutches to walk, as the pressure from using them can affect the veins in the arm.

- If a person has a constant cough or is vomiting regularly. The increased pressure within the chest can lead to the catheter being in the wrong position, wearing away, or even leading to a serious condition where fluid builds up around the heart (cardiac tamponade).

Equipment used for Percutaneous Central Catheter

PICC lines, or long thin tubes that doctors put into a large vein in your arm and then into your heart to give you medicine or fluids, can be different in their length, ranging from 50 cm to 60 cm. They can also differ in the number of channels they have, which can be either one, two, or three. Furthermore, some can be maintained and cared for differently than others.

Additionally, PICC lines can have valves or not. Valves in these tubes are useful to stop the blood from flowing back into the tube, especially when the setup is open.

There are different brands of these tubes available in the market, and there might be minor differences in their packaging and accompanying equipment. The most commonly used method for inserting a PICC line is known as the modified Seldinger technique. Here is a general list of standard equipment your doctor may use if they use this technique:

* An ultrasound machine and a sterile cover for the probe with ultrasound gel

* Sterile gloves and gown, face shield mask, and hair cover

* Sterile sheets and towels used to cover skin that should not be exposed

* A solution for cleaning the skin (usually contains chlorhexidine and alcohol)

* Sterile saltwater used to clean the lines

* A tape measure

A typical PICC line insertion kit includes:

* The PICC line tube

* Needles of different thickness

* Syringes with a capacity of 10 mL

* A guide wire to help introduce the PICC line

* A device called a dilator to widen the pathway for the line

* An introducer which helps in inserting the line

* A small blade for making the initial incision

* A local anesthetic (often lidocaine) for numbing the area

* Materials for stitching the area if needed

* A specialized sterile dressing kit (usually clear and lets the skin breathe)

Who is needed to perform Percutaneous Central Catheter?

A Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter (PICC), a type of tube put into a large vein, can be inserted by various health care professionals like doctors, registered nurses, or physician assistants who have undergone special training. Some places have teams of nurses specifically trained for putting in PICCs. These specialists have been shown to increase the success of inserting the tube properly and safely, while lowering the chances of problems happening. They do this by using proper, clean techniques in a cost-effective way. This means they can do the job well without costing too much money.

Preparing for Percutaneous Central Catheter

Central venous catheters, which are tubes placed into a large vein to provide medicine or collect blood samples, can be inserted surgically or non-surgically. Peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs), a type of central venous catheter, are typically inserted non-surgically without needing a major operation. This is usually done at the patient’s bedside with the help of ultrasound, which provides real-time images and significantly improves the success of the procedure.

Like with any other medical procedure, preparing and having all the required materials and tools at hand is critical for a successful outcome.

To ensure your safety, a sterile technique—this means using practices that keep germs from causing infections—is used during this procedure. Following standardized guidelines for placing the catheter, as well as for caring for, maintaining, and preventing infection after the catheter has been inserted, can greatly reduce the chance of developing catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSIs). These infections can occur when bacteria or other germs travel along a central venous catheter and enter your bloodstream. So, keeping everything clean and sterile is vital.

The details of how the entire procedure is performed, from getting ready for the PICC insertion to the procedure itself, are in the Technique section provided.

How is Percutaneous Central Catheter performed

There are other ways to insert a PICC, like using a peel-away needle, but they need big veins and can cause problems like too much bleeding or trapped air in the veins. So, the Seldinger technique is the most common.

Here are the steps a healthcare provider takes when placing a PICC line:

1. They ask for your consent for the procedure.

2. They gather the necessary supplies.

3. They measure your arm’s size, to check if any swelling happens after the placement.

4. They decide which vein will be used for the procedure, usually with the aid of an ultrasound image.

5. They apply a band to make your veins more visible. It helps if you drink lots of water beforehand.

6. They mark the spot on your skin where they’ll insert the PICC line.

7. They measure how long the catheter will need to be to reach the right place near your heart.

8. They cleanse your arm with an aseptic solution.

Next, the medical team member will wear a mask with a face shield, a hair cover, sterile gown, and gloves. They will put sterile towels around you and apply a numbing medication on your skin if needed. They locate the vein again using an ultrasound image.

They insert a needle into your vein and feed a wire through it. They remove the needle but leave the wire in place. They will gently cut your skin next to the wire to make room for a dilator.

The next step is to insert the dilator along the wire, which creates enough room for the PICC line to slide into place. They then remove the wire and dilator, leaving only the catheter behind. The healthcare provider advances the PICC Line to the right length and removes the introducer.

A doctor will then confirm the PICC line is placed correctly by taking a chest X-ray. Only after proper placement has been confirmed, it can be used.

Once your PICC line is in place and working as it should, it needs regular maintenance. This includes stabilizing the line, cleaning it with solutions, and changing the dressing regularly to keep infections away.

Possible Complications of Percutaneous Central Catheter

When a tube known as a catheter is placed inside the body, there is always a chance of infection. This may lead to skin infections (cellulitis), small pockets of pus (abscesses), or bloodstream infections (bacteremia) which can spread to the rest of the body. Some bacteria are more commonly associated with these types of infections. These can especially occur in a hospital environment, the most common of which are coagulase-negative Staphylococci, Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococci, and Candida.

For a specific type of catheter called PICCs (Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters), the overall infection rate is 1.1 for every 1000 days a catheter is in use. This rate is found to increase in a hospital (inpatient) setting. This could be because patients who are treated at home and outside of the hospital are generally healthier and their catheter is not accessed as often. Whether PICCs or CICCs (Centrally Inserted Central Catheters) show lower rates of infection is currently under debate. Some studies suggest PICCs might lead to slightly fewer infections among critically ill patients, but more recent studies have found no difference.

Infections are more common with PICCs placed in the antecubital fossa, which is the area of your arm inside the elbow, than those placed in the upper arm. Other factors that can increase the risk of infection are non-tunneled catheters (inserted directly into a vein and not secured under the skin) and catheters with multiple openings.

Preventively giving antibiotics has not consistently shown to prevent infections; so it’s not typically used. However, catheters coated with germ-killing substances have been proposed to lower the chances of infection. You might assume changing catheters often can prevent infection, but this is not recommended for PICCs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advises against changing PICCs routinely to prevent bloodstream infections.

A catheter may need to be removed for many reasons including: infections around the insertion site or along the pathway the catheter takes under the skin, septicemia (serious bloodstream infection), fungemia (fungus in the blood), septic thrombosis (blood clot caused by infection), endocarditis (infection of heart lining), osteomyelitis (bone infection), and sepsis with signs of bodywide illness and organ dysfunction.

How the catheter is positioned matters. It could be improperly placed in the wrong vein or it may move after insertion. This can occur for various reasons like unusual vein arrangement, changes in the patient’s position during insertion or changes in the pressure inside chest veins due to coughing or vomiting. Misplacement or movement can disrupt blood drawing, cause damage to the heart, or create a life-threatening condition, all of which need to be immediately addressed.

Incorrect positioning or movement of the catheter can be evaluated using chest x-rays or a contrast dye to visualize the veins. Correcting the positioning can often be achieved using simple techniques at the bedside (like having the patient turn their head or changing their breathing pattern). Properly securing catheters at the insertion point can also prevent their movement.

About 10-27% of PICCs can stop working due to mechanical problems. A catheter can move up and down inside a vein leading to irritation and inflammation. They can shift and get lodged in tiny blood vessels during placement, or become fractured internally that usually requires surgical removal. Phlebitis (inflammation of a vein) and infiltration (fluid leakage into surrounding tissues) can occur in 2.2-23% of patients with PICCs due to physical damage or irritation from certain medications. This can be treated using anti-inflammatories or warm compresses.

Air emboli, or air bubbles that obstruct blood flow, are rare but potentially life-threatening complications that can occur if the closed system between the catheter and blood vessels is disturbed. This can happen due to catheter damage, disconnection of the catheter, lack of proper dressings, improper line flushing, among others. Like a cardiac tamponade, this is a medical emergency and requires immediate attention.

It’s also possible to have abnormal heart rhythms if the catheter tip is positioned too far into the heart. Adjusting the position of the catheter can typically correct the problem.

Another potential issue is catheter occlusion, or blockage, which can happen due to a blood clot or non-blood clot related reasons. The risk of getting a blood clot can be as high as 78% if the catheter tip is positioned high in the superior vena cava (a large vein that carries blood from the body back to the heart), compared to 16% if the tip is in the distal superior vena cava/right atrium (part of the heart).

Non-thrombotic causes include the catheter pressing against the wall of a blood vessel or getting twisted, or a build-up of medication residue. Common medications known to cause this type of occlusion include etoposide, calcium, diazepam, phenytoin, heparin, and total parenteral nutrition, a special liquid food given into a vein. Properly flushing catheters before and after taking blood samples or administering medications, and ensuring that medications and solutions are compatible can prevent these occlusions. Additionally, repositioning a patient or catheter can resolve occlusions due to catheter kinking or impingement.

What Else Should I Know About Percutaneous Central Catheter?

Central venous access devices are safe and highly efficient tools used for administering medications and fluids in hospitalized patients, particularly those in Intensive Care Units (ICU). Since they were introduced in the 1970s, these devices have also become popular for outpatient care, especially for people who need regular treatments outside of the hospital. One such device is the Peripheral Inserted Central Catheter (PICC).

PICCs have several benefits over other central catheters. They can be used for several weeks up to 6 months for injecting medications and liquids, compared to non-tunneled CICCs which are typically used only for several days. PICCs are easier to access because the access point is in the arm, and they can deliver the same medications and fluids at similar rates to other central catheters. The beauty of PICCs is that they can be easily inserted and removed by nurses at the patient’s bedside, unlike other central catheters which require a surgical procedure to be placed. Another distinctive advantage of PICCs is that they can also be used safely in patients with low platelet counts, whereas central ports are riskier due to the possibility of internal bleeding from the frequent needle punctures needed for access.

However, there are some limitations to PICCs. They are usually smaller, which is less useful for frequent blood tests (although a syringe can still be used). Also, for patients who need daily access for procedures such as stem cell transfers or blood product administration, centrally inserted catheters placed surgically are generally preferred. Furthermore, other types of catheters, like those which are tunneled and implantable ports, can function for a duration longer than six months, while PICCs are usually not used for such prolonged periods (although they have been surprisingly functional for more than 300 days on rare occasions).

To summarize, PICCs are a great option for a variety of diagnostic tests and treatments, offering a safe and effective method for accessing the central vein. They have been proven to be more cost-effective and have lower complication rates than non-tunneled CICCs, which has boosted their popularity in intensive care settings.