What is H1N1 Influenza?

H1N1 flu, a type of influenza A virus, is a contagious virus that can cause infections in the upper and sometimes, lower parts of the respiratory system. This can lead to symptoms like runny nose, cough, loss of appetite, fever, chills, muscle pain, headache, and possibly, diseases in the lower respiratory and digestive systems. Influenza A and B viruses are the main types affecting human health, although there are other strains as well.

There are three kinds of swine flu that affect the world–H3N2, H1N2, and H1N1. The H1N1 flu, often known as “swine flu,” became a global concern during the 2009 pandemic. This happened after swine flu viruses were mixed with existing H1N1 strains. The “swine flu” was a result of a mix of previous swine, bird, and human flu strains, leading to a worldwide outbreak that affected millions of people and industries like food and tourism.

H1N1 flu leads to a respiratory disease that can infect the breathing systems of pigs. People can get swine flu if they are closely exposed to infected pigs. If the virus changes its characteristics by mixing with different flu strains, swine flu viruses have the potential to infect humans. This could increase replication and transmission, making it easier to transfer the virus to humans. Such mixes have led to pandemics, as we saw in 1918 and 2009, when the virus became capable of efficient person-to-person transmission.

In 1918, the H1N1 flu virus, also known as the Spanish flu, led to a devastating pandemic. It infected about 500 million people worldwide and resulted in the deaths of an estimated 50 to 100 million people, which was 3% to 5% of the world’s population at that time, making it one of the deadliest pandemics in history. Similarly, in 2009, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined the H1N1 flu outbreak as a pandemic. The 2009 H1N1 virus spread from person to person through air droplets, possibly through objects contaminated with the virus, and then transferred to the mucus layers or upper respiratory tract.

Interestingly, the symptoms of H1N1 in humans and pigs were similar, potentially because the virus mixed with existing strains. This suggests that there may be a common way the virus causes disease across multiple hosts, possibly because of the mixing of strains, thus making transmission more efficient. During this pandemic, many people mistakenly believed that they could get swine flu from eating pork products like bacon, ham, etc. However, the virus is only found in the respiratory system and not in blood, so transmission through food is unlikely. This misunderstanding led to significant financial losses in the food and tourism sectors.

What Causes H1N1 Influenza?

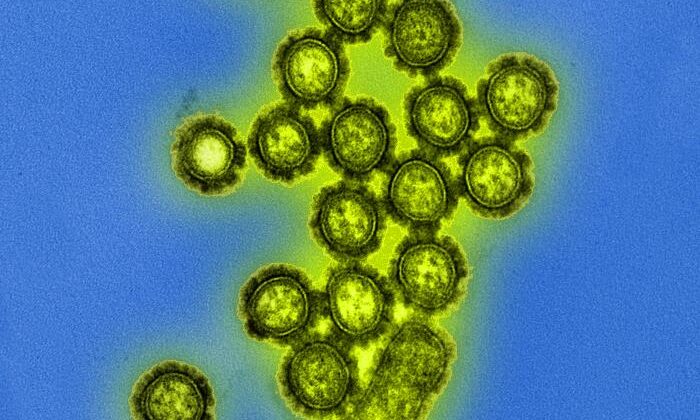

The H1N1 flu virus is a part of a group called orthomyxovirus. It has a single-stranded, negative-sense RNA genome, meaning its genetic material is composed of RNA strands in a particular configuration. The size of this virus is usually around 80 and 120 nm in diameter, with an RNA size of about 13.5 kb. It contains 8 different regions in its genome that code for 11 different proteins.

These proteins include envelope proteins, like Hemagglutinin (HA) and Neuraminidase (NA), which are crucial in how the virus behaves. It also has viral RNA polymerases (PB2, PB1, PB1-F2, PA, and PB), matrix proteins (M1 and M2), and nonstructural proteins (NS1 and NS2). These nonstructural proteins are important for the virus’ ability to cause disease and reproduce itself.

The H1N1 strain of the flu is different from other strains, such as H1N2, because of the presence of specific surface proteins hemagglutinin and neuraminidase. Hemagglutinin helps the virus to stick to cells in the body by binding to sialic acid, a substance on the surface of cells. It then enables the virus to enter the cell through a process called endocytosis. Afterward, the virus’ RNA-dependent polymerase begins to reproduce the virus within the cell. Neuraminidase also plays a key role in helping the virus spread to neighboring cells by cutting off sialic acid receptors.

Risk Factors and Frequency for H1N1 Influenza

The H1N1 influenza virus was first identified in pigs in the 1930s and quickly became known as a cause of flu in pigs around the world. In some cases, humans in close contact with pigs contracted the flu, and pigs were also able to catch the human flu from their handlers. The virus can jump between species, mutating and changing over time to avoid being targeted by our immune systems.

Major changes in the virus’s proteins can result in new flu strains that can evade the immune system and spread from person to person. The 2009 H1N1 flu pandemic in Mexico, for example, came from multiple strains combining, including a form of bird flu, a human flu, and a pig flu.

The 2009 H1N1 pandemic led to between 151,700 to 575,500 deaths from respiratory and heart issues in the first 12 months, with almost a quarter of the world’s population believed to have been infected. The devastating 1918 flu pandemic, which infected around 500 million people and resulted in 50 to 100 million deaths, was also caused by the H1N1 flu virus. The 2009 “swine flu” was a descendant of the 1918 strain.

Although flu strains like H1N1 often pass between pigs and humans, it’s not common for them to spread from person to person. However, the 2009 H1N1 strain was easily spread between pigs and people. Pigs can act as a reservoir, carrying strains of the flu virus that have disappeared in humans. These strains can then resurface and infect humans if the virus mutates or our immunity wanes. This continuous evolution can lead to new variants that pose a threat to unprotected humans.

Signs and Symptoms of H1N1 Influenza

H1N1 swine influenza is a virus that can cause various symptoms, ranging from mild cold-like symptoms to severe breathing problems that can lead to death. The way it affects someone depends on their age, health conditions, vaccination and natural immunity to the virus. Its symptoms are similar to the seasonal flu and include fever, chills, cough, runny nose, sore throat, eye inflammation, muscle pain, breathing difficulties, weight loss, headache, nasal congestion, lightheadedness, stomach discomfort, decreased appetite, and fatigue. However, H1N1 often causes more coughing, muscle pain, and chest discomfort compared to normal influenza. The 2009 strain of H1N1 was also linked to increased vomiting and diarrhea.

Since many of the symptoms of H1N1 are similar to other illnesses, a detailed patient history is crucial, especially if the patient has been exposed to confirmed H1N1 cases or have recently travelled to areas where the disease is common.

During the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, severe cases often resulted in breathing failure and shock, leading to death. Other severe effects included mental confusion, delirium, strokes, digestive tract bleeding, secondary bacterial infections, heart attacks, heart failure, inflammation of the heart, and kidney damage requiring dialysis. This version of the virus tended to affect children and adults under 60 more severely.

Pregnant women, particularly in their second and third trimesters, were more at risk of severe symptoms during the 2009 pandemic. Other risk factors for extreme disease included a high body mass index (BMI equal to or greater than 35 kg/m2), chronic health conditions, and starting antiviral treatment more than five days after the symptoms had begun. The list of chronic conditions that amplified risk include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchial asthma, reduced immunity, chronic liver disease, neurological disorders, and diabetes.

- Fever

- Chills

- Cough

- Runny nose

- Sore throat

- Eye inflammation

- Muscle pain

- Breathing difficulties

- Weight loss

- Headache

- Nasal congestion

- Lightheadedness

- Stomach discomfort

- Decreased appetite

- Fatigue

- Vomiting (more common with 2009 strain)

- Diarrhea (more common with 2009 strain)

Testing for H1N1 Influenza

Influenza A (H1N1) virus can cause a range of symptoms and show up in different clinical settings. It is crucial to consider H1N1 if a patient has symptoms like the flu or sudden pneumonia, especially if there are known cases of flu in the area. To make a diagnosis, doctors will usually start with standard tests like bloodwork, microbe cultures, biochemistry tests, and imaging studies.

To confirm a H1N1 influenza A virus diagnosis, a sample from the patient’s respiratory system is needed. This can be a swab from the nose and throat, or a sample of fluid from there. A number of tests can be run on these samples, including RT-PCR, viral cultures, complementary fixation testing, haemagglutination assays, and antibody detection by immunofluorescence. To check for a change from one type of antibody (IgM) to another (IgG), or an increase in influenza virus IgG antibody levels, more serological tests can be performed. However, all these tests may not always detect animal versions of the virus.

A new type of swine flu might be suggested if an influenza A virus test comes back positive, but key proteins that usually appear in human flu viruses are missing. Serological tests run after the fact might sometimes be able to catch animal strains of the flu virus, but these can be complicated because there could be cross-reactions with human flu viruses. There’s also a concern that some swine flu viruses’ key envelope proteins, which are the main targets of our bodies’ immune response, might have originated from human flu viruses that circulated in human populations before. Depending on the health department in charge, either state, regional, or national public health labs might be able to do genomic testing and test for new types of flu viruses.

Treatment Options for H1N1 Influenza

Many of the strategies used to manage ordinary flu can also be applied to H1N1 flu, except in cases where the flu comes from animals. In these situations, prevention works best. It’s important to control the flu outbreaks in pigs, minimize pig-to-human transmission, and ultimately stop the disease from spreading among humans.

To prevent the flu in pigs, it’s critical to manage the pig facilities properly, avoid overcrowding, and separate sick pigs from healthy ones. Vaccination also plays a significant role. But vaccinations alone may not be enough to stop the disease from spreading among pigs without additional prevention measures.

Preventing pig-to-human transmission is critical to controlling the spread of H1N1 flu in people. It’s essential to reduce the incidence of the flu in pigs, but it’s equally important to prevent the flu from jumping from pigs to humans. This is usually a risk for people who work closely with pigs, like farmers or vets, who should wear face masks and use good hygiene practices.

Stemming the spread of H1N1 among humans mostly involves practicing good hygiene: washing hands often and cleaning surfaces with diluted bleach solution. People who think they have the flu should stay home from work, avoid public transportation, and see a doctor immediately.

During the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, a vaccine was approved which was shown to give protection after a single dose. This vaccine should not be given to people who have had a severe allergic reaction to the flu vaccine or to people who are currently feeling moderately to very ill.

The way H1N1 flu is treated will depend on how severe the symptoms are. Mild to moderate cases can often be managed with rest and drinking lots of fluids. Antipyretics, antihistamines, and simple pain relievers can also help manage symptoms. However, people with severe symptoms should be treated in a hospital, especially if there is a risk of respiratory failure, sepsis, or multiple organ dysfunction.

Medical professionals should be aware that early treatment with antiviral medication might help reduce the severity of the disease and deaths. Medications like oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir, have been shown to help reduce the effects of H1N1 flu if taken within 48 hours of getting symptoms.

Pregnant women who get the H1N1 flu are at higher risk of complications. The babies of women who had H1N1 while pregnant can also have a higher chance of being born early or with growth restriction. Therefore, it’s especially important for pregnant women to be vaccinated against the H1N1 flu, as recommended by the US’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization.

What else can H1N1 Influenza be?

When a doctor is diagnosing a condition, they need to consider all potential diseases or infections that could cause similar symptoms. This is known as forming a differential diagnosis. For example, a range of conditions could look like H1N1 influenza, including:

- HIV

- COVID-19

- Adenovirus

- Arenavirus

- Cytomegalovirus

- Dengue

- Echovirus

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome

- Parainfluenza virus infections

- Legionnaires disease

- Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia

- Cryptococcal pneumonia

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae infections

The viruses that have symptoms most similar to the H1N1 influenza include COVID-19, regular seasonal flu, and parainfluenza virus infections. This means that a complete and careful evaluation is necessary to distinguish the H1N1 influenza from these similar conditions.

What to expect with H1N1 Influenza

The 2009 influenza pandemic, caused by the H1N1 virus, had a mortality rate of around 1%. Older individuals (aged 50 and above) were less likely to get infected, but young children (aged 5 or younger) and early teenagers (aged between 5 and 14) had higher rates of hospitalization. People with chronic medical conditions faced a greater risk of severe disease. Key lab results in severe cases showed elevated levels of certain proteins and reduced number of lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell).

Several factors were linked with an increased risk of death or need for intensive care (ICU) admission in H1N1 influenza. These included diabetes, steroid therapy, use of certain antihistamines, severe obesity, as well as secondary heart and bacterial complications. Furthermore, a study of 1,651 patients during the 2009 pandemic found that delaying treatment with an antiviral drug (oseltamivir) for more than 5 days was linked with a higher likelihood of hospitalization, ICU admission, and increased risk of death.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with H1N1 Influenza

The 2009 H1N1 flu pandemic strain mostly caused problems with the respiratory system, such as pneumonia, the worsening of chronic lung disease, and, to a smaller degree, ARDS (acute respiratory distress syndrome). Heart-related complications and follow-up bacterial infections could also worsen the situation. Some people experienced seizures, focal neurological deficits, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and myositis. After a year of H1N1 influenza, it was noted that individuals had increased shortness of breath when exerting themselves, lower rates of return to work, and higher rates of anxiety and depression compared to those without H1N1-related ARDS. All of this highlights the importance of prompt and appropriate treatment to avoid both immediate and long-term complications.

Potential issues due to the H1N1 Influenza:

- Respiratory issues like pneumonia and worsened chronic lung disease

- Cardiovascular complications

- Additional bacterial infections

- Neurological complications like seizures and Guillain-Barré syndrome

- Increased rates of anxiety and depression

- Reduced frequencies of returning to work

Preventing H1N1 Influenza

Preventing the H1N1 flu virus, which is a germ that impacts the respiratory system (the parts of your body that help you breathe), is possible through good personal cleanliness and controlling your immediate surroundings. Regular habits like wearing masks, washing your hands frequently using soap and water, antiseptic cleansers, or sanitizers with alcohol can help.

It’s important to always clean your hands before touching your face. Knowing the correct way to cover your mouth and nose when coughing or sneezing, paired with keeping a safe distance from others, are effective ways to limit exposure to any germs in coughs or sneezes. Another preventative measure is frequently cleaning surfaces that germs may be on, using cleaning agents such as alcohol, bleach solutions, or quaternary ammonia compounds.