What is Sideroblastic Anemia?

Sideroblastic anemia is a type of anemia where the body doesn’t use iron correctly when making new red blood cells. There are different versions of this anemia, but they’re all identified by a specific kind of cell in the bone marrow – the ring sideroblast. These are immature red blood cells with iron gathered around the cell’s nucleus, forming a ring shape. This iron-based ring takes up at least a third of the rim of the cell’s nucleus. Depending on what caused the abnormality, sideroblastic anemia can result in anemias with either small or larger than normal red blood cells. It differs from anemia due to iron deficiency, where the body has low iron stores, because people with sideroblastic anemia usually have normal to high iron levels. Other types of anemias with small red blood cells include thalassemia and anemia of chronic disease.

The hemoglobin molecule, which helps carry oxygen to tissues in the body, contains a vital protein called heme. This protein has a specific structure with four pyrrole rings connected by four methine bridges, all centered around an iron atom. Besides forming part of hemoglobin, heme also plays a role in recognizing gases, transmitting signals, controlling the body clock, maintaining our day-night rhythm, and processing micro RNA.

Sideroblastic anemia happens because of a problem during the process of making heme in the production of new red blood cells. 85% of heme is made in the body of the young red blood cells and in mitochondria, while the rest is made in hepatocytes, cells in the liver. In the Shemin pathway, one of the ways the body makes heme, eight different enzymes ensure everything goes as it should.

There are two main types of sideroblastic anemia: hereditary and acquired. The details about the causes, frequency, differential diagnosis (how to tell the difference between similar diseases), the process of the disease, treatment, and management of sideroblastic anemia will be discussed next in this article.

What Causes Sideroblastic Anemia?

Sideroblastic anemia comes in two types: hereditary and acquired. The hereditary type happens because of changes in certain genes involved in the creation of part of the red blood cells responsible for carrying oxygen (heme synthesis), assembly of parts of the body’s cells (iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis), or the generation of energy in cells (mitochondrial metabolism). These gene changes can occur on the x chromosome, affecting certain enzymes like aminolevulinate synthase (ALAS2), adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette B7 (ABCB7), or glutaredoxin 5 (GRLX5). There can also be changes in other genes, including the mitochondrial transporter (SLC25A38) and the mitochondrial DNA. The most common cause of this hereditary type is a change of the gene responsible for the ALAS2 enzyme.

Such gene changes can cause two different kinds of anemia: microcytic anemia, which is related to smaller than normal red blood cells, or macrocytic anemia, which is related to larger than normal red blood cells. The type of anemia someone gets depends on which specific gene undergoes a change.

The acquired type of sideroblastic anemia can come from either primary or secondary causes. Primary causes might include blood disorders like myelodysplastic syndrome with ring sideroblast (MDS-RS) and refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts RARS, which are typically due to a mutation in the splicing factor 3b subunit 1 (SF3B1) gene that plays a significant role in the shaping of RNA.

Secondary causes are usually due to external factors like medication, toxins, copper deficiency, or long-term diseases that cause uncontrolled cell growth. Certain antibiotics, hormones, copper-binding agents and chemotherapy drugs are known to be the most common drugs that cause sideroblastic anemia. Things like alcohol usage, exposure to lead, and isoniazid usage can also result in sideroblastic anemia.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Sideroblastic Anemia

Sideroblastic anemia is categorized as a rare disease. Rare diseases are those that affect less than 200,000 people in the US. Because it’s so uncommon, exact numbers on how many people have this anemia are not known.

Signs and Symptoms of Sideroblastic Anemia

Sideroblastic anemia is a condition where the body has trouble making healthy red blood cells. Patients with this condition often experience symptoms like feeling tired, being generally unwell, having shortness of breath, feeling their heart beat faster or harder than usual, and headaches. Physical check-ups may show signs like pale eyes and skin, or in some cases, skin that looks bronze due to an overload of iron in the body.

There are different types of sideroblastic anemia. Some people are born with it; this is known as hereditary sideroblastic anemia. They might have additional symptoms like uncontrolled diabetes or hearing loss. This hereditary type often occurs in the young who have a family history of the condition. On the other hand, some people develop sideroblastic anemia later in life, which might be connected to another condition called myelodysplastic syndrome.

- Feeling tired

- Feeling generally unwell

- Having shortness of breath

- Heartbeat feels faster or harder than usual

- Headaches

- Pale eyes and skin (possible symptom)

- Bronze-looking skin due to iron overload (possible symptom)

- Uncontrolled diabetes and hearing loss in hereditary types (possible symptoms)

Testing for Sideroblastic Anemia

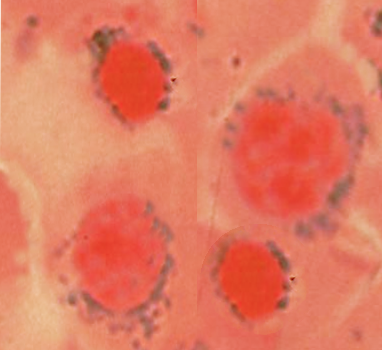

Sideroblastic anemia is identified when iron-containing inclusions, known as ring sideroblasts, are found in the bone marrow. The red blood cells carrying these iron deposits are referred to as siderocytes. Normally, a complete blood test will show that the patient’s average blood cell volume is low, indicating smaller than usual red blood cells. The blood test would also show low average cell hemoglobin and increased varying sizes of red blood cells.

By using a specific test called Perl’s reaction, ring sideroblasts can be confirmed. After this, the doctor should look at the patient’s bone marrow for signs of other disorders or abnormal production of red blood cells. If an abnormality is found, the patient could be suffering from myelodysplastic syndrome, which is a group of disorders caused by poorly formed blood cells.

Otherwise, the patient may have congenital (something you’re born with) or acquired sideroblastic anemia (developed later in life). In some cases, patients might have larger than average red blood cells, particularly in case of a specific subtype called RARS.

If the cause of sideroblastic anemia is still not clear after secondary acquired sideroblastic anemia is excluded, doctors should consider genetic testing.

Treatment Options for Sideroblastic Anemia

The treatment for sideroblastic anemia depends on how severe it is. If the condition is mild or not causing any notable symptoms, doctors can monitor the situation with regular check-ups.

For those diagnosed with a specific form called X-linked sideroblastic anemia, taking 50-100mg of the vitamin pyridoxine (also known as vitamin B6), each day has been found to help improve or completely correct the anemia. However, not everyone responds to this treatment. For these individuals, blood transfusions could be necessary if their anemia is severe.

If someone needs regular blood transfusions, they might accumulate too much iron in their body. To prevent this iron overload, they might need to take drugs that help to remove excess iron, such as deferoxamine or oral chelators. Starting this when blood tests show that the amount of a protein called ferritin—which stores iron in the body—exceeds 1000 ng/L is usually recommended.

Iron overload could also hamper the effectiveness of pyridoxine. Therefore, even patients who manage to maintain normal hemoglobin (the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen) levels with pyridoxine, could need phlebotomy (a procedure to remove some blood). Treating iron overload is crucial because studies indicate better anemia management and pyridoxine responsiveness when iron levels are lower.

In a different type of the condition known as syndromic congenital sideroblastic anemia, patients could also develop diabetes. These patients should aim to keep their blood sugar levels well controlled. If they can’t manage their blood sugar well, they could develop low blood sugar, also known as hypoglycemia.

If a drug or toxin causes another variant named secondary acquired sideroblastic anemia, it’s essential to stop using the offending substance. Removing it often leads to an improvement in the anemia as this type is acquired, not inherited.

In case someone has developed the condition due to a shortage of copper, they should incorporate more copper-rich foods in their diet to overcome the deficiency.

For patients with a certain specific condition called MDS/MPN-RS-T, which is associated with sideroblastic anemia, taking aspirin might be recommended in case they also have a specific gene mutation known as JAK2V617F.

What else can Sideroblastic Anemia be?

When trying to identify sideroblastic anemia, doctors need to distinguish it from similar conditions, both hereditary and acquired. Some of these are illnesses tied to irregularities in cellular or genetic structure, such as different types of myelodysplastic syndromes. Other conditions that can be confused with sideroblastic anemia are not tied to genetic abnormalities. These can be either inborn or developed later in life, and include copper deficiency, excess zinc, lead poisoning, and the use of a specific drug called isoniazid.

What to expect with Sideroblastic Anemia

The outlook for sideroblastic anemia can vary depending on the cause of the condition. If this type of anemia is caused by drugs or toxins (known as secondary acquired sideroblastic anemia), the outlook is generally positive once these substances are stopped. On the other hand, X-linked sideroblastic anemia is a genetic condition, and its outlook can be improved with proper treatment, including using pyridoxine (a type of Vitamin B) and managing iron levels in the body. However, if this condition isn’t managed correctly, the outlook can be less favorable.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Sideroblastic Anemia

Sideroblastic anemia, a type of anemia that can be caused by changes or mutations in certain genes (specifically, XLSA, GLRX5, and SLC25A38), has been reported to lead to an overload of iron in the liver and throughout the body. This situation, known as iron overload, comes about as a result of ineffective production of red blood cells due to mitochondrial iron toxicity, which causes iron absorption to increase. Then this excess iron is primarily stored in the liver, eventually leading to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, conditions similar to those found in genetic hemochromatosis.

In rare cases, iron overload can also lead to heart problems. The excess iron could accumulate in the heart, leading to irregular heart rhythms and even heart failure.

Preventing Sideroblastic Anemia

For children with inherited sideroblastic anemia, they often rely on parents or guardians to make health decisions for them. Therefore, it’s crucial for parents and caregivers to understand this type of anemia and how to help manage it. This includes making sure that these children stay away from food high in iron, as it could make their condition worse. To keep up-to-date and make the best decisions, regular check-ups with a blood specialist (a hematologist) are recommended.

Another crucial aspect in the management of this medical condition is ensuring the child takes all prescribed medicines appropriately, which might include drugs like pyridoxine and possibly some that help to reduce iron levels in the body. These drugs play an important role in improving health outcomes in kids with this genetic form of anemia.

Practicing a balanced diet to guarantee that the child gets enough vitamins and minerals is also essential. Finally, to prevent worsening sideroblastic anemia, avoid exposure to alcohol, a medication known as isoniazid, and lead poisoning. These factors can cause a different type of this anemia, known as the acquired form, even in those already suffering from the inherited form.