What is Malignant Tumors of the Palate?

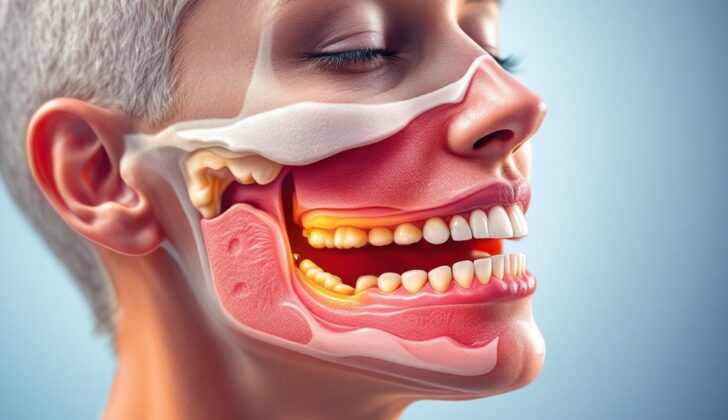

Cancers in the hard and soft palate of the mouth can have many different features. The hard palate, which is part of the oral cavity, includes horizontal plate of the palatine bone and the palatine process of the maxillary bone – bones in your mouth. Its borders are the gum ridge at the front, the soft palate at the back, the nasal cavity at the top, and the oral cavity at the bottom. The hard palate consists of small saliva glands and has a close link between its mucosa (the moist tissue lining the inside your mouth) and the surrounding layer of the bones. This unique make-up leads to a different range of cancers than other areas in the mouth.

The soft palate, on the other hand, is part of the oropharynx, which is the part of the throat at the back of the mouth. Its borders are the hard palate at the front, muscles at the sides, and the uvula (the small fleshy part that hangs down at the back of the mouth) at the back. The most common types of cancer in the hard and soft palate include squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC), adenoid cystic carcinoma (AdCC), polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma (PLGA), low-grade papillary adenocarcinoma (LGPA), acinic cell carcinoma (ACC), mucosal melanoma, Kaposi sarcoma, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). These are all various types of cancer that can affect the cells in this region.

What Causes Malignant Tumors of the Palate?

Tobacco and alcohol are known to cause cancer and can contribute together to cause oral SCC, a form of mouth cancer. Reverse smoking, where the lit end of the cigarette or cigar is held in the mouth, has been associated with the development of cancerous lesions on the hard palate, or roof of the mouth. This unusual way of smoking can heat the palate up to 50 degrees Celsius, and it’s believed that the heat may also contribute to causing cancer. Other risk factors like poor oral hygiene, constant injury to the oral mucosa (inner lining of the mouth), ill-fitting dentures, infection with Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), harsh mouthwashes, and lack of vitamin A have been connected to these palate lesions.

The causes of cancers in the minor salivary glands, such as AdCC, MEC, PLGA, LGPA, and ACC, are not known but are thought to be linked to certain gene mutations, ageing, and hormonal influences.

Mucosal melanoma is a rare and aggressive type of cancer that can develop on the palate. It is believed to start from melanocytes, which are cells found in the base layer of the oral mucosa and are responsible for skin color. The precise cause of this cancer is unclear, but factors such as ill-fitting dentures, tobacco use, and existing benign oral lesions with melanin (skin pigmentation) have been suggested in scientific literature. Unlike skin melanoma, sun exposure is not considered a risk factor for mucosal melanoma due to its development inside the mouth. Some people might have this form of cancer without noticeable pigmentation change, known as amelanotic melanoma.

Kaposi’s sarcoma is associated with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). It is connected to weakened immune systems and is the first cancer thought to originate from acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

The risk factors for developing Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (NHL), a cancer that starts in the lymphatic system, are several and include immune system suppression (due to HIV, innate immunodeficiency, organ transplant, chemotherapy, and radiation), viral infections (such as EBV, HTLV-1, Herpes, Hepatitis C), bacterial infections (like Helicobacter pylori gastritis and Lyme disease), tobacco, consumption of animal fat, obesity, hair dyes, sun exposure, pesticides, exposure to workplace toxins, and gene defects related to B-cell (a type of white blood cell) survival and growth.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Malignant Tumors of the Palate

In the mouth, only around 1 to 5% of all oral cavity cancers are found on the hard palate, which is the part of the roof of the mouth that contains bone. Out of all these cancer types, a few specific types account for most cases.

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) is the most common kind of oral cavity malignancy, even though it’s less frequent on the palate than on other subsites. Typically, this type is found in males in their 60s.

- Minor salivary gland tumors, often malignant, are very typical for the hard palate, with AdCC and MEC being the most frequent types.

- AdCC (Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma) forms as the most common type of salivary gland cancer on the palate, and women are found to be more prone to it.

- MEC (Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma), the most common salivary gland cancer overall, appears second most frequently in the minor salivary glands of the hard palate. It’s more prevalent in younger female patients.

- PLGA (Polymorphous Low-Grade Adenocarcinoma) and ACC (Acinic Cell Carcinoma) are more common in women and typically appear in people in their 50s to 70s.

- Mucosal melanomas and Kaposi sarcoma are less common but can occur in the hard palate. These types of cancers are more common in certain ethnic groups and often occur in older individuals.

- NHL (Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma) is a type of cancer that can also appear in the hard palate, particularly at the junction of the hard and soft palate. It’s usually found in white males over the age of 65.

However, it’s important to remember that no matter the type of cancer, early detection and treatment are key to successful recovery.

Signs and Symptoms of Malignant Tumors of the Palate

People with a growth on their palate, which is the roof of the mouth, may notice bad breath, bleeding in their mouth, dentures that don’t fit well, difficulty swallowing, painful swallowing, changes in their speech, and loose teeth. It’s important to gather detailed information about any pain, when the growth first appeared, how fast it’s growing, difficulty swallowing, instances of bleeding, and any oral injuries that may have happened in the past. Information about a patient’s past health, surgery history, any family history of cancer, and social risk factors such as smoking, drinking alcohol, using drugs, and exposure to occupational risks should be acquired.

A physical exam including a full head and neck check focused on the mouth should be performed. Palatal malignancies are mostly found as a growth on the palate with or without oral bleeding and pain. It’s crucial to feel both sides of the neck for any swollen lymph nodes. Hard palate SCC is usually associated with swollen lymph nodes in 13.7% to 25.7% of cases, mainly in the area of the throat and neck.

- AdCC can present with pain even before any visible lesion. It grows slowly and often spreads beyond what can be seen or felt.

- MEC appears as a slow-growing, painless, and red-blue tinted mass. It might feel firm due to a build-up of a slimy substance within the tumor.

- PLGA presents as a painless, slow-growing mass without any ulcerated mucosa and might resemble a benign tumor.

- LGPA is a painless, lobulated, soft, yellow-tan and solid mass.

- ACC, a rare type of salivary gland cancer, can occasionally appear in the hard palate. It is a painless, slow-growing mass.

- Mucosal melanomas are flat or rounded lesions with a pigmented dark brown to black color. Most tumors within the oral cavity are 2 to 6 cm in size.

- Kaposi sarcoma presents as deep reddish-brown patches, raised skin, plaques, or growths that protrude outwardly. They can occur on the mucosal membrane, skin, lymph nodes, and internal organs.

- NHL usually presents as a painless, submucosal mass at the junction of the hard and soft palates with no ulceration but with swollen lymph nodes.

Testing for Malignant Tumors of the Palate

When a doctor suspects a patient has a cancerous growth on the roof of their mouth (also known as a palatal malignancy), they’ll follow several steps to make a diagnosis. They’ll start with a patient’s medical background and a physical examination of the mouth. They’ll also use special tests like CT scans, MRIs, or PET scans, and even take a sample of the suspicious tissue (biopsy).

A CT (also known as a Computerized Tomography) scan is a type of X-ray which provides a detailed picture of the insides of your mouth. It helps the doctor see how far the suspected cancer has spread, if it has damaged any bones, or if it’s moved into your lymph nodes (the tiny, bean-shaped organs that help fight infection). Believe it or not, MRIs (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) can sometimes provide more precise pictures of soft tissues like gums and the tongue than CT scans. A possible downside to CT scan is that dental work, like fillings and crowns, can sometimes get in the way of clear images.

With MRI, doctors can even figure out if cancer has spread along nerves or moved into your neck’s lymph nodes. When the doctor is looking at an MRI of a potential mouth cancer, they’ll look for blurred borders of the growth, signs that the cancer has spread along nerves or into nearby structures, or if it’s missing what’s known as a “capsule” (a sort of wall of tissue that can surround benign or non-cancerous growths). Also, terrifyingly, cancer in the roof of your mouth can even creep into a skull cavity known as the “pterygopalatine fossa”, or widen the holes in your skull that our palate’s nerves pass through.

There is another type of X-ray called a “panoramic X-ray” which gives the doctor a comprehensive view of your jawbone and teeh to see if they’re affected. PET (Positron Emission Tomography) scans, while not ideally suited for detailed anatomy, are particularly good at finding lymph node involvement, distant spread of disease, and for keeping tabs on patients who’ve already been treated.

A biopsy is when the doctor removes a small piece of the suspicious tissue to examine it more closely. This can either be an ‘incisional biopsy’ (where just part of the tissue is taken), a ‘punch biopsy’ (where a small circular ‘punch’ of tissue is taken) or a ‘Fine-Needle Aspiration’ (FNA – where a thin needle is used to remove small bits of tissue). The accuracy of an FNA biopsy can vary, depending on the doctor’s skill and how they go about it. In fact, sometimes the biopsy needs to be done while the patient is under anesthesia so the doctor can get more information about how large and extensive the suspected cancer is.

Treatment Options for Malignant Tumors of the Palate

Treating cancer of the roof of the mouth often involves a variety of treatments and depends on a few factors. These factors include the specific type, stage, and extent of the cancer, and the overall health of the patient, especially their ability to tolerate cancer treatments. The first step is to remove as much of the cancer as possible while keeping the surrounding area of healthy tissue untouched. This is most often used for cancers of the roof of the mouth.

However, if the cancer is more serious, or if it has spread to the neck, additional surgery might be needed for better cancer control. After the initial surgery, further treatments like chemotherapy and radiation therapy might be needed. This is especially the case for serious cancers, if cancer cells are on the edge of the removed tissue, if cancer has spread to the neck, if it has invaded nerves, or if it has come back after earlier treatment.

Radiation alone isn’t effective for gland cancers of the mouth as they are resistant to it and it often spreads to the bone. For a specific type of cancer called Kaposi sarcoma, antiretroviral treatment is used for patients with low counts of a type of white blood cell (CD4) or high counts of the virus that causes it. Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, another type of cancer, is primarily treated with chemotherapy and radiation together.

What else can Malignant Tumors of the Palate be?

When diagnosing cancers of the roof of the mouth, or palatal malignancies, the physician might need to rule out a list of other conditions that can mimic similar symptoms. These conditions include:

- Neurofibroma: A type of typically benign nerve tissue tumor

- Neurilemmoma: A benign tumor of the nerve sheath

- Schwannoma: A typically benign tumor that grows from Schwann cells

- Lipoma: A benign fatty lump

- Pyogenic granuloma: A small, benign skin growth

- Follicular lymphoid hyperplasia: A benign condition of the lymph nodes

- Necrotizing sialometaplasia: A benign condition of salivary glands

- Multiple myeloma: A type of bone marrow cancer

- Ewing sarcoma: A rare type of bone or soft tissue cancer

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis: A rare disease involving an excess of specific immune cells

- Leukemia: A type of blood and bone marrow cancer

- Osteosarcoma: A type of bone cancer

- Osteomyelitis: An infection in the bone

- Abscess: A collection of pus

- Tuberculosis: A bacterial infection that usually affects the lungs

- Mucocele: A harmless cyst or swelling in the mouth

- Leiomyoma: A benign smooth muscle tumor

- Pleomorphic adenoma: A common type of non-cancerous salivary gland tumor

- Other rare benign minor salivary gland tumors, including basal cell adenoma, myoepithelioma, and cystadenoma

Careful examination and appropriate tests are needed to differentiate these diseases and identify the correct diagnosis.

Surgical Treatment of Malignant Tumors of the Palate

Transoral surgery, which is a procedure conducted through the mouth, is commonly chosen to treat small and superficial palate tumors that are not lymphomas. However, if the tumor affects the hard palate or the underlying bone, a more extensive procedure might be required to completely remove the tumor. This could range from surgically removing a part of the palate to a more comprehensive surgery that removes portions of the maxilla, the upper jaw bone. Such surgery may result in physical changes, which would then need to be covered with a removable artificial device or by transferring tissue.

If the tumor is too large or too deeply spread into areas not accessible through the mouth, the surgeon may have to use external approaches. These can include creating a variety of flaps or openings, such as splitting the upper lip, to have adequate access to the tumor. It might even require partial or complete removal of the maxilla. During the operation, the surgeon will make sure that the tumor’s edges are free of malignant cells through a technique known as frozen section analysis.

If the tumors are very extensive and require a significant portion of the palate or maxilla to be removed, this could interfere with crucial functions like talking, chewing, and swallowing. In such instances, the deficit may be covered with temporary artificial devices, or tissue taken from other parts of the body, depending on the size and location of the deficit.

Palate tumors often grow into the bone due to their proximity, and they might not respond adequately to radiation therapy. Hence, surgery remains the best option.

The likelihood of spread of cancer from the hard palate to the neck was earlier believed to be low, leading many surgeons to avoid aggressive neck surgery in patients with no evidence of disease in the neck at the time of diagnosis. However, recent studies indicate that this spread can occur in up to 40% of patients, prompting surgeons now to electively remove neck lymph nodes in advanced disease states. The need for removal of these lymph nodes in early disease states requires more research.

An excision that ensures no residual malignant cells at the margins of the tumor combined with removal of neck lymph nodes is the primary treatment for a number of malignancies, including AdCC, MEC, PLGA, LGPA, ACC, and mucosal melanoma. The presence of neck lymph nodes significantly improves survival rates in patients with advanced disease states. In cases of mucosal melanoma, non-surgical intervention can increase the risk of death by 21-fold. For patients with widespread Kaposi’s sarcoma who do not achieve satisfactory cosmetic results with chemotherapy, combining cryotherapy with curettage has been proposed as a supplementary treatment.

What to expect with Malignant Tumors of the Palate

The likelihood of recovering from malignant tumors of the palate, which are cancerous tumors in the roof of your mouth, can greatly vary based on a number of factors. These include the specific type of tumor, the severity of the tumor, whether it’s spread to the edges of the tissue sample, if it has spread to your neck, and if it has reappeared after treatment.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), a type of skin cancer, has worse survival rates if the cancer is highly severe, has already spread, or if it comes back. Positive margins (cancer cells found at the edge of the tissue sample) and spread to the neck also affect survival rates. However, it’s possible that having a specific virus (HPV) in the tumor might increase chances of survival. An additional treatment called radiation therapy has been shown to be beneficial for survival as well. Despite the palatine bone near the tumor often being affected due to the thin lining of the mouth, it doesn’t negatively affect survival.

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (AdCC), another type of cancer that primarily affects the salivary glands, has an overall 5-year survival rate ranging from 60% to 90%, but this rate reduces to 40-50% after 10 years. The cancer variant called ‘solid variant’ has the worst outcomes due to increased chances of the cancer spreading and returning. Other factors that contribute to worse outcomes include positive margins, spread to the neck, old age, involvement of the bone, invasion of nerves, and the size of the tumor.

Mucinous Epithelial Carcinoma (MEC), a form of cancer that commonly affects the salivary glands, has varied survival rates based on its severity. Low-grade (less severe) MEC has an over 90% survival rate after 5 years, while high-grade (more severe) MEC often spreads and returns.

Polymorphous adenocarcinoma (PLGA), another type of salivary gland cancer, and low-grade papillary adenocarcinoma (LGPA) demonstrate different tendencies for recurrence and spread to the neck. PLGA often slowly reappears for decades after initial treatment, while LGPA tends to recur faster and spread to the neck more frequently.

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC), a rare form of cancer that can occur anywhere in your body, has a 88.6% survival rate over 5 years. Factors that jeopardize chances of survival include high tumor severity, advanced development of the tumor, spread to the neck, and old age.

Mucosal melanoma, a type of skin cancer that affects the mucous membranes in your body, never has good prognosis. It’s often detected when the cancer has invaded more than 5mm of the tissue or has spread to the neck.

Kaposi’s sarcoma, a type of cancer that causes lesions in the skin, can be dangerous if left untreated with an average survival of 18 months. However, treatments for HIV can improve overall survival rates for AIDS patients affected by Kaposi sarcoma.

Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma (NHL), a type of cancer that originates in your lymphatic system, shows promise when treated with radiation therapy. But aggressive cases, specifically Burkitt’s lymphoma and DLBCL, show worse survival rates compared to less aggressive ones. Patients with HIV have a shorter survival time compared to those without HIV.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Malignant Tumors of the Palate

The main risk of surgery for oral cancer is not fully removing the disease, which can lead to it returning in the same area, spreading to other parts of the body, or developing a new primary cancer. Surgical removal of parts of the mouth can lead to difficulties with speech and swallowing, potentially resulting in a need for long-term feeding assistance, repeated inhaling of food into the lungs, and communication challenges. Loss of feeling and the extra tissue presence from surgical reconstruction can also make it harder for patients to chew food properly. Patients who undergo surgery on the neck for cancer spread to lymph nodes run the risk of damage to various nerves.

Common Side Effects of Surgery:

- Not fully removing the disease

- Return of disease in the same area or elsewhere

- Development of a new primary cancer

- Difficulties with speech and swallowing

- Need for long-term feeding assistance

- Repeated inhaling of food into the lungs

- Challenges with communication

- Harder to chew food due to loss of feeling and extra tissue

- Risk of nerve damage with neck surgery

Normal side effects of radiation are common and usually not life-threatening. More recent radiation techniques have significantly reduced damage to the saliva-producing glands, reducing xerostomia or dry mouth. Patients might experience acute side effects such as inflammation of the mucous membranes, throat, esophagus, difficulty swallowing, painful swallowing, jaw stiffness, dry mouth, and skin inflammation. In some cases, severe side effects such as mandibular osteoradionecrosis (damage to the lower jawbone due to lack of blood supply) can occur.

Chemotherapy for mouth cancer can lead to various complications such as inflammation of the mucous membrane, fungal and viral infections, dry mouth, change in taste perception, malnutrition, and pain. Certain chemotherapy drugs can increase the incidence and severity of these complications. Reduced saliva production resulting from chemotherapy increases the risk of oral yeast infections, gum disease, inflammation of the mucous membranes, change in taste perception, tongue cracks, bad breath, oral pain, and painful swallowing. When chemotherapy is given concurrently with radiation, it can further increase the risk of damage to the lower jawbone due to increased reactive oxygen species, which affects the DNA repair capability of bone cells.

Common Side Effects of Radiation and Chemotherapy:

- Inflammation of the mucous membranes, throat, esophagus

- Difficulty swallowing, painful swallowing

- Jaw stiffness, dry mouth, skin inflammation

- Damage to the lower jawbone due to lack of blood supply

- Fungal and viral infections

- Change in taste perception, malnutrition, and pain

- Oral yeast infections, gum disease

- Tongue cracks, bad breath, oral pain

- Increased risk of damage to the lower jawbone if chemotherapy is given with radiation

Recovery from Malignant Tumors of the Palate

Patients who have been treated for oral cancers often experience long-lasting changes to their swallowing and speech abilities. This can be due to different parts of the mouth being removed during surgery, scarring from radiation treatment, and mouth sores from combined chemotherapy and radiation treatment. Early meetings with professionals who specialize in speech and swallowing can be extremely beneficial in helping the patient regain some of their abilities before treatment started. This can prevent malnutrition, accidental inhalation of food or drink, long-term reliance on tube feeding, and difficulty in communicating.

Unfortunately, the cancer can come back many years after the initial treatment, so continued check-ups are necessary. Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network suggest that after treatment, patients should have regular check-ups every 1 to 3 months for the first year, every 2 to 6 months for the second year, every 4 to 8 months for years three to five, and then annually after the fifth year. They recommend these check-ups continue for over 10 years for these types of cancers.

Preventing Malignant Tumors of the Palate

Explaining palatal cancer (a type of cancer that happens in the roof of your mouth) can be a bit complicated due to different types and growth patterns of the disease, and the need for a team of doctors using different treatments. It is important to teach patients and their families about the different treatment plans and how long they may take. These treatment options might include surgery to remove the tumor, radiation therapy or chemotherapy (both are used to kill cancer cells), along with possible reconstructive surgery to address severe damage to the roof of the mouth. Parents and patients (if the patient is a minor) need to be informed about the possible risks and complications related to these treatments.

The patient’s general condition should be thoroughly examined by their primary doctor to decide if they are suitable for surgical removal of the tumor. Patients should be urged to quit habits like smoking and drinking, as these factors can increase the chances of cancer coming back and can also hamper treatment results.

Given the high chances of this type of cancer coming back and the slow-growing nature of these tumors, it is incredibly important to have long-term follow-up appointments with the doctors. This is crucial in identifying any recurrence early and must be strongly emphasized to the patients.