What is Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy?

Corneal dystrophies (CD) are a group of eye diseases, passed on through genes, which affect only one or more layers of the cornea – the clear, front layer of the eye. These diseases are often present in both eyes, progress slowly, and do not have other effects on the body. They usually develop as a result of a dominant gene, meaning a person only needs one copy of the gene from either parent to have the condition. Some people might experience blurred vision, a feeling like something is in their eye, pain, sensitivity to light, and tearing.

One such condition is Posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD) which was identified by Koeppe in 1916. This rare, hereditary eye condition can vary greatly among different family members who have it. People with PPCD have a layer at the back of the cornea, called the Descemet membrane, which is unusually thicker than normal. They might start to have symptoms like swelling of the cornea at a very early age. But, most people with the condition do not have symptoms and only find out they have it during a routine eye check-up years later.

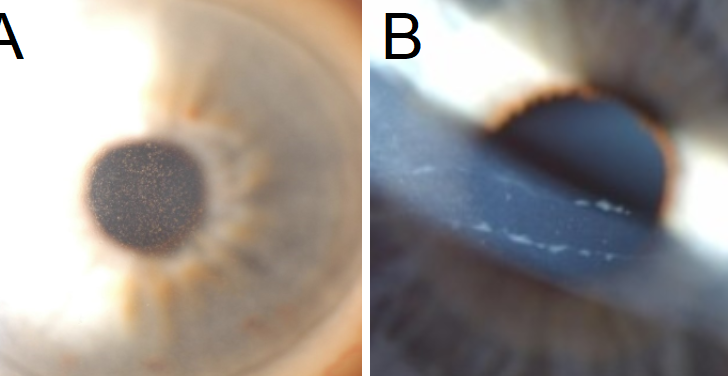

In PPCD, the dystrophy, or disease, typically affects both eyes, though one eye could be worse than the other. Symptoms either remain the same or develop very slowly over time. The best way to detect this condition is by closely examining the back of the cornea, especially the Descemet membrane and the nearby corneal endothelium (the inner layer of cells). In this condition, the Descemet membrane becomes irregularly thick due to groups of blister-like sores and grey-white spots causing the back of the cornea to become opaque. There could be three different patterns in which the sores appear: vesicular (blister-like), band-like, or diffuse. Doctors use a specific microscope (slit lamp biomicroscope) with medium to high magnification for this.

PPCD may also spread to the iris (the colored part of the eye) and the anatomical angle (the corner where the cornea and iris meet). The abnormal cells from the back of the cornea can move across the chamber angle and onto the peripheral iris surface. The abnormal layer they produce can give the iris a glass-like appearance and can also lead to other issues like corectopia (displacement of the pupil) and pupillary ectropion (outward turning of the pupil). The presence of such abnormal cells may also contribute to glaucoma, an eye condition that damages the optic nerve. Additionally, swelling in the outer part of the cornea may be seen over any wide areas of iridocorneal adhesion (where the iris sticks to the cornea).

What Causes Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy?

Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy (PPCD) is a disease of the eye that affects the cornea, and it’s a condition that can vary greatly from person to person and can be caused by different genes. Understanding what’s happening at a genetic level, it’s all about different types of mutations (changes to the normal order and structure of genes) in a number of different genes.

PPCD can occur in four known forms, named PPCD1, PPCD2, PPCD3, and PPCD4. Each one is caused by a mutation in a different gene:

- PPCD1 is caused by a mutation in a gene called OVOL2, which is located in a particular part of our genetic material known as 20p11.22.

- PPCD2 happens because of a mutation in the COL8A2 gene, which you’d find located at 1p34.2-p32.3.

- PPCD3 is linked to a mutation in the ZEB1 gene, located at point 10p11.22.

- PPCD4 is caused by a mutation in the GRHL2 gene, found at 8q22.

Remember, the different gene locations like ‘20p11.22’ are like specific addresses on our genetic material (DNA), where these specific genes are found.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy

Posterior polymorphous dystrophy (PPCD) is an extremely rare condition. Many patients don’t show symptoms, so it’s hard to determine exactly how common it is. We do know that it affects both men and women equally. Interestingly, the Czech Republic seems to have a higher than average number of cases, with reports estimating about 1 case in every 100,000 people.

Signs and Symptoms of Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy

Posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD) is often a condition that doesn’t cause any symptoms. It’s typically found during regular eye exams. This condition can be inherited, so it’s important to know if there’s a history of corneal disease in the family. Those who don’t have any symptoms mostly have normal or near-normal eyesight. Glaring is one of the common symptoms noted. During a thorough eye exam, irregularities in the innermost layer of the cornea can be seen in both eyes. Though this condition affects both eyes, the symptoms can be uneven.

- It’s a hereditary condition

- Patients usually have normal or near-normal vision

- Glare symptoms are frequent

- Both eyes have irregularities in their innermost layer

- Symptoms can be uneven in both eyes

The abnormal areas on the cornea can look different in different people, with clusters of blister-like formations being the most common. Sometimes these abnormalities appear as parallel bands with scalloped edges across the visual field. Larger, clouded areas are rare, but when present, they’re more likely to affect vision. It’s important to find out when the signs or symptoms started. Young children during their critical developmental period may develop ‘lazy eye’ or amblyopia due to this condition. The cornea’s irregularities could lead to its steepening and high astigmatism. A significant difference in refraction in both eyes can lead to another form of lazy eye, anisometropic amblyopia. Occasionally, the cornea can swell up right at birth. Any lasting opacity in the cornea’s center may contribute to amblyopia. If there are any signs to indicate that the endothelium, the innermost layer of the cornea is affected, then it’s important to inspect the eye’s drainage system.

Unusual adhesion of the iris to the cornea, known as peripheral anterior synechia (PAS), can be found alone or in wide bands. Over these bands, there might be swelling of the outer edge of the cornea. If there’s an increase in the eye’s internal pressure or any distortions of the iris or pupil, it’s essential to check for glaucoma, a group of eye conditions that damage the optic nerve, crucial for vision.

Testing for Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy

Using a special instrument called a slit-lamp biomicroscope, your doctor can closely examine the back of your cornea in real time. This allows them to directly see changes on the cornea that vary in shape, size, and appearance, known as polymorphous lesions.

These lesions can also be looked at with instruments that give moderate to high magnification using direct or, preferably, retro-illumination techniques.

Another imaging technique called specular microscopy is used to capture high-resolution images of changes related to PPCD within the thin, protective outer layer of your eye’s cornea (Descemet membrane) and its innermost layer (endothelial layer). With PPCD, the number of cells in the endothelial layer may decrease, and the remaining cells often show irregular shapes and structures.

Confocal microscopy is another tool your doctor can use to clearly identify the specific features characteristic of PPCD, a rare hereditary eye disorder that affects the cornea.

It’s also essential for your doctor to measure your eye pressure to check for any signs of glaucoma, a condition that causes damage to your eye’s optic nerve.

Your doctor may also use a technology called anterior segment optical coherence tomography (OCT) to see any abnormalities caused by the endothelium (innermost layer of the cornea) protruding into the angle between the cornea and the iris. Because this disease can be passed down through families, it could be helpful for family members to also get examined to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment Options for Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy

If you don’t have any symptoms but are found to have posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (a rare eye disorder that affects the cornea), your doctor should explain its presence and possible significance to you.

In children with high or unequal vision correction needs, a treatment known as amblyopia therapy can be started. This is also true for young children who have previously had corneal swelling that affected their ability to see shapes. Children with ongoing corneal swelling should be referred to a children’s eye specialist right away.

If you have this corneal condition, you’ll need to have your posterior (or back) corneal layers checked regularly. Should you experience surface-level corneal erosions or a particular type of corneal disease known as bullous keratopathy, a bandage-like soft contact lens could be helpful.

When updates in the layer of cells lining the inside of your cornea (endothelial) are found, a procedure called gonioscopy should be done to take a closer look at the eye’s drainage angle.

If your eye’s internal pressure is too high, that could be a sign of glaucoma – a group of diseases damaging your eye’s optic nerve. It’s important to start a thorough check-up for glaucoma. If diagnosed with this condition, generally the first treatment is a type of eye drop that reduces the pressure in your eyes, called a prostaglandin analog. If this doesn’t bring your eye pressure down enough, you may need to use different kinds of medications or add more medications. Surgery might be recommended if maintaining strict control of your eye pressure is impossible with medication alone. Minimally invasive glaucoma surgery or MIGS is anticipated to provide great results.

For individuals with distorted iris or pupils, a glaucoma check-up should be started. If corneal transplant surgery is needed, penetrating keratoplasty (PF) has historical success. However, PK has been associated with slow and challenging recovery as well as variable visual results.

If the front layers of your cornea are fine, the procedures – Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) or Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) are preferred. However, if there are adhesions or ‘sticky’ areas where the iris attaches to the cornea, these corneal transplant procedures have a higher risk of not succeeding.

What else can Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy be?

- ICE Syndrome (also called Chandler’s syndrome)

- Birth-related cornea disorder (Congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy)

- Disease of the inner layer of the cornea (Pre-Descemet corneal dystrophy)

- Fuchs endothelial dystrophy (a disorder that affects the innermost layer of the cornea)

- Glaucoma at birth (Primary congenital glaucoma)

- Descemet’s membrane break due to injury (Traumatic rupture of Descemet membrane)

What to expect with Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy

The outlook for those with Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy (PPCD), an eye disease, depends on how far the disease has advanced.

* Many times, PPCD is either non-progressing or progresses very slowly.

* How often patients need to go for check-ups depends on how severe their disease is.

* People who are diagnosed in adulthood with a mild form of the disease generally have a good outlook and often don’t need treatment.

* If a child’s eyes are not coordinated and focused properly (a condition called anisometropic amblyopia), immediate attention is necessary.

* Infants with swollen corneas need immediate treatment to prevent the development of ‘lazy eye’ which can happen if their vision is neglected (a condition called deprivation amblyopia).

* Patients with adhesions (abnormal growths) between the iris and cornea should be checked for a disease called glaucoma.

* Those with high eye pressure, vision field defects, or a certain kind of optic nerve damage associated with glaucoma should be treated for this disease.

* A cornea transplant procedure (penetrating keratoplasty) may be needed if cornea cloudiness affects their vision potential.

If abnormal growth between the iris and cornea is present, corneal transplant procedures may not succeed.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy

Babies and toddlers could develop problems with their visual development, called amblyopia, if there are disruptions in the development of their visual system.

- It is essential to take measures to prevent this, especially in the ‘critical period’ up to the age of 3, and is strongly advised until the age of 9.

- If prescribed a bandage soft contact lens (BSCL) therapy to prevent complications, patients must be well-versed in handling and taking care of the BSCL.

- Wearing BSCL could potentially lead to infection, discomfort and vision loss if there is a secondary infection in the cornea.

- People with adhesions (attachments of iris and cornea) need to be closely observed for glaucoma – a serious eye condition.

- Those showing signs of high pressure inside the eye, defects in viewing fields, or an appearance of an optic nerve affected by glaucoma, should be considered for treatment of glaucoma.

- If the cornea becomes cloudy, thereby hindering vision, a corneal graft should be considered – this is known as penetrating keratoplasty.

- If adhesions are present in the iris and cornea, there is a higher chance that the corneal grafting procedure may fail.

Please note, an inherited eye condition that affects the cornea, called Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy, has a risk of recurring in corneal grafts.

Preventing Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy

For patients who don’t show any symptoms but have mild signs of a condition called posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD) – a rare genetic eye condition that can affect vision – it’s important that they understand what this means and how it can affect them in the future.

To detect this condition early, vision tests are crucial. Young children with strong or uneven vision impairment may need special treatment called amblyopia therapy. They may need to be checked regularly by an eye doctor to look for abnormalities in the front part of their eyes.

If their cornea – the clear layer at the front of their eye – seems swollen and doesn’t get better, the child should see a pediatric eye doctor right away. Amblyopia therapy may be recommended if the swelling in the cornea affects how they see shapes.

If there are signs that the innermost layer of their cornea is affected, a gonioscopy – a type of eye test – should be performed to look at the drainage angle of the eye. If the pressure inside the eye is high or there are any abnormalities in the iris or pupil, thorough testing for glaucoma should be carried out. Glaucoma is a common eye condition where the optic nerve, which connects the eye to the brain, becomes damaged.

If glaucoma is diagnosed, treatment is very important. Treatment options can include eye drops, laser therapy, different types of surgery – including minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS), which is a less invasive procedure that uses tiny devices to reduce eye pressure.

A laser procedure called peripheral iridotomy (LPI) is not recommended if there is new cell growth on the drainage system in the eye. If the eye pressure can’t be controlled, a type of glaucoma surgery to drain fluid from the eye might be necessary.

If patients need a cornea transplant, a traditional full thickness transplant, known as a penetrating keratoplasty (PK), has generally had good results, but recovery can be slow and challenging. An alternative type of grafting procedure that only replaces part of the cornea, called a lamellar corneal transplantation, can offer faster recovery with better vision results.

For instance, Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) can be done if the outer parts of the cornea are healthy, while Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) is preferred if the front and middle layers of the cornea are healthy.

However, if there are adhesions – bands of scar tissue – between the cornea and the colored part of the eye, then corneal transplant procedures have a higher chance of not being successful.