What is Retinal Detachment?

The retina is the innermost layer at the back of the eye. It has multiple layers, with the outermost layer being the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and the innermost layer being the internal limiting membrane (ILM). Retinal detachment occurs when the functional layer of the retina separates from the RPE, the layer that supports it.

The light-sensing cells (photoreceptors) are on the outer part of the retina and depend on another layer, the choroid, for oxygen and nutrients. The central part of the retina (the fovea) has no blood vessels and relies entirely on the choroid. The fovea can be damaged if it detaches, which can potentially be reversed if it is reattached promptly. However, even with surgical intervention, if the fovea detaches again, vision may remain poor.

There are three types of retinal detachment: rhegmatogenous, tractional, and exudative. Rhegmatogenous detachments, which are the most common, occur when fluid leaks from the vitreous (the clear, gel-like substance inside the eye) through a tear in the retina into the space between the retina and the RPE. Tractional detachments happen when connective tissues contract and lift the retina. Both rhegmatogenous and tractional elements may lead to detachment. Exudative detachments are caused by the build-up of fluid beneath the retina resulting from diseases affecting the retina or choroid. Sometimes, a retinal detachment can be a combination of these types.

What Causes Retinal Detachment?

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) happens when there’s a tear or break in the retina, allowing a jelly-like substance called vitreous to seep into the space beneath the retina. Sometimes there can be a pulling force on the retinal break that keeps it open, which makes it easier for the vitreous to get in.

There are a number of risk factors for RRD:

* Lattice degeneration, a condition where the retina thins out.

* Retinal breaks or holes/tears like atrophic hole, operated hole, horseshoe tears, giant retinal tears, and retinal dialysis.

* Trauma to the retina or damage due to an infection.

* Conditions like pathological myopia (a severe kind of shortsightedness) or macular holes.

* Past eye surgery or trauma.

* Certain genetic disorders like Stickler syndrome or Marfan syndrome.

* A family history of retinal detachment.

Next, there are tractional retinal detachments (TRD). They happen when scar tissue grows on the retina’s surface and the contraction of the scar tissue pulls the retina away from the back of the eye. The risk factors for TRD include:

* Advanced stages of diabetic retinopathy (damage to the retina due to diabetes).

* A type of disease from blood not flowing properly through the retinal veins called retinal vein occlusion.

* Previous eye injuries.

* Premature babies with retina issues.

There are also exudative or serous retinal detachments (ERDs), where fluid leaks into the space beneath the retina without any retinal breaks. Causes of ERDs include:

* Primary ocular tumors and secondary eye tumors that spread from other parts of the body.

* Conditions like sarcoidosis, an inflammatory disease, or syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease.

* Conditions like Central Serous Chorioretinopathy (CSCR) where fluid builds up under the retina.

* Pregnancy complications like pre-eclampsia or eclampsia.

* Previous organ transplantation.

* A condition called Acute retinal necrosis.

* Coats disease, causing abnormal development in blood vessels.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Retinal Detachment

The chance of getting a Retinal Detachment (RRD) can vary based on different studies. Some studies estimate that 1 in 10,000 people can get RRD, while others indicate an annual risk between 6.3 to 17.9 per 100,000 people. Some factors might affect the likelihood of getting an RRD.

- Men may have a slightly higher risk of getting an RRD than women.

- People from Southeastern Asia may have a higher chance compared to those of European White race. This might be linked to the fact that people from Southeastern Asia often have a higher risk of nearsightedness and longer eye shape.

- However, a different study revealed no significant difference in risk factors, treatment outcomes, and clinical features among patients with retinal detachments from different ethnic groups in Singapore (Indian, Malay, and Chinese).

Signs and Symptoms of Retinal Detachment

Retinal detachment is a condition that can exhibit various symptoms. More often than not, patients with Retinal Detachment (RRD) complain about seeing random floaters and sparks of light in their vision. They might also experience a loss in their field of vision that begins on the outer edges and gradually shifts towards the center. Understanding different aspects of medical history, like the exact timing of symptom onset, a history of similar symptoms in the non-affected eye, any impact on overall visual clarity, previous surgeries or trauma, and any procedures done to treat near-sightedness, like LASIK, can be helpful in diagnosing this condition.

Different aspects of diagnosing retinal detachment include evaluating each eye for visual acuity, checking pupil reactions, and testing the confrontation visual field. Doctors often check the eye’s internal pressure too, as retinal detachment can cause a decrease in pressure.

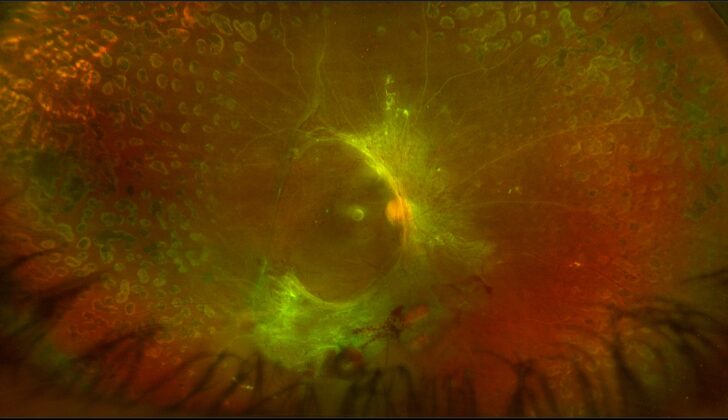

A key part of the diagnosis includes a detailed eye examination using a slit lamp to check for abnormalities. After that, doctors would typically perform a dilated eye exam. Important signs include the appearance of pigment in the vitreous of the eye, or an abnormal amount of blood. If any portion of the retina isn’t visible, or if the view is obstructed, examination using ultrasound may be necessary.

- New-onset floaters in vision

- Random light flashes in vision

- Progressive/ fixed visual field loss

- Checking the visual acuity of each eye

- Checking each eye’s pupillary reaction

- Confrontational visual field testing

- Checking the intraocular pressure

- Slit lamp examination of the anterior segment

- Dilated fundoscopic examination

- Possible use of ultrasound for examination

Other forms of retinal detachment include Tractional Retinal Detachment (TRD) and Exudative Retinal Detachment, both of which exhibit distinctive characteristics. TRD usually causes a gradual loss of vision due to an abnormal growth on the retina that pulls it out of place. Other signs of the disease causing this type of detachment, like proliferative diabetic retinopathy and branch retinal venous occlusion, could be present.

Exudative Retinal Detachment is usually characterized by the retina’s fluid shifting downwards. In these cases, there’s no retinal break or any abnormal pigmentation in the vitreous. Other symptoms of the causative condition may be present.

Testing for Retinal Detachment

If your doctor suspects that you might have a retina detachment (RD), they will refer you to an eye specialist, such as an ophthalmologist or optometrist. The specialist will carry out a detailed examination of your eye using a particular type of microscope called an indirect ophthalmoscope. The procedure will involve dilating your pupil and pressing gently on your eye to give the specialist a clearer view of your retina.

Other imaging techniques include ultrasound scans, computed tomography (CT) scans, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. More often than not, if a retina detachment is suspected, CT and MRI scans are not needed unless there’s a chance that you might have a mass or cancer inside your eye. Ultrasound, when done by an experienced healthcare provider, can be very effective at diagnosing a detached retina. This method is quite accurate, with a study showing that it correctly identifies a retina detachment 94.2% of the time and correctly determines when a retina detachment isn’t there 96.3% of the time.

In an ultrasound scan, certain features can help distinguish a retina detachment from other conditions. For instance, the detached retina usually looks like a thick membrane that’s attached to both sides of the optic nerve head (the area where the optic nerve enters the eye). The detached retina also produces strong reflections when the ultrasound rays hit it and stays visible even when the ultrasound machine’s sensitivity is reduced.

If available, a technique known as optical coherence tomography (OCT) can be useful in evaluating all three types of retina detachments and differentiating a detached retina from other eye conditions.

If it’s determined that you likely have the most common type of retina detachment called rhegmatogenous, there are specific guidelines to follow to locate the retinal tear or hole that’s causing the detachment. For example, if the detachment is at the top of your eye (either in the temporal or nasal area), the causative break is usually located within the top 1.5 hours of the clock face of your eye. For detachments at the bottom of your eye, the causative break usually lies on the side of the optic nerve that’s higher.

For cases of detached retina that involve “bullous” or blister-like formations at the bottom of the eye, the originating tear or hole is often located at the top of the eye.

Treatment Options for Retinal Detachment

The treatment for two types of retinal detachment, “RRD” and “TRD”, is usually surgery. If you are diagnosed with these conditions, you might have to see an eye specialist (known as a retinal specialist or an ophthalmologist) who has extra training in the back part of the eye. They will be able to advise you on treatment and possibly perform any surgical treatments needed.

If the problem is an “RRD”, the surgeon’s job is to find and fix any openings or rips in the retina. There are three main ways they might do this: a procedure called a “pars plana vitrectomy”, another called a “scleral buckle”, or a process called “pneumatic retinopexy”. On occasions, they might even combine these procedures. The choice between these procedures depends on various factors such as your specific symptoms, the surgeon’s expertise, and the cost of each operation. While there is disagreement on which procedure is the best overall, one procedure might be more useful in certain situations.

A “pars plana vitrectomy” is a procedure where a special machine mechanically removes the vitreous gel, which fills the your eye, from the eye. This is done to relieve any pressure on the retina, which could cause the retina to tear. In this procedure, the surgeon will make three points of entry from the side of your eye, each serving a unique purpose: lighting, for the cutting tool, and to add a solution to the eye. The surgeon then removes any pull on the retina and uses a freezing treatment or a laser to seal the opening or tear. Sometimes they even use a gas or silicone oil to help seal it. However, if silicone oil is used, you may need another surgery to remove it.

The “scleral buckle” method involves putting a permanent silicone band around your eye, causing the outer layer of the eye to push in, which helps close the tear in the retina. This is often done in combination with a “retinopexy” procedure, which involves using a freezing process to help the retina reattach properly.

In “pneumatic retinopexy”, the eye doctor injects a gas bubble inside your eye. This helps the fluid underneath the retina to be absorbed and allows a bond to form around the tear, preventing further damage. The effectiveness of this method depends on the size of the gas bubble and also maintaining a specific position after the surgery so that the gas bubble can press against the tear. This method is typically used when there is a single, small tear located on the upper part of the retina.

In cases of “tractional detachments”, the pulling forces causing the detachment, usually unhealthy tissues or membranes on or under the retina, must be removed. This is typically done with the “pars plana vitrectomy” procedure, and sometimes a “scleral buckling” is also done to further support the retina.

As for “serous or exudative retinal detachments”, which actually involve a buildup of fluid under the retina rather than a tear, they are typically managed non-surgically. Instead, the doctor will identify and treat whatever underlying condition is causing the buildup of fluid.

What else can Retinal Detachment be?

When a doctor suspects a retinal detachment, they have to consider other conditions that might be responsible for the symptoms. These could include:

- Retinoschisis

- Fluid buildup in the choroid layer of the eye, or choroidal effusion

- A mass in the choroid layer

- A hemorrhage above the choroid layer

The doctor can distinguish between these conditions by using a special device to examine the back of the eye and other appropriate imaging techniques. If the patient has lost part or all of their vision in both eyes, the doctor should also consider the possibility of a stroke. Retinal detachment should also be considered in patients who have another type of retinal detachment known as tractional retinal detachment.

Huge bleeding under the retina from various causes can also lead to retinal detachment. This can be due to aging-related changes in the eye, abnormal blood vessels in the eye, blood disorders, use of blood-thinning medicine, and physical injury.

What to expect with Retinal Detachment

The outlook for retinal detachment (RD) varies widely depending on the type of detachment and the patient’s condition when they seek help. For something called a Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD), a key factor is whether the macula, or the center of the retina, stays attached. In one study, it was found that in 83% of patients where the macula was still attached, their vision could be corrected impressively well, to at least 20/40. Even if the macula was detached, having surgery promptly didn’t affect the final outcome of their sight.

Unfortunately if the macula is detached, the prospects for vision recovery are not as good. Despite this, about half of patients who receive surgery within the first week get their vision improved to at least 6/15. As such, it’s advisable to have surgery within the first week if the macula has detached, although it doesn’t need to be done as an emergency within the first 24 hours. Some experts argue that if surgery is done within 72 hours, the final results might be almost as good as if the macula was still attached, especially in prioritized cases.

The patient’s vision could be worse if there’s something called submacular fluid, which is fluid underneath the macula. However, the phakic status, which is whether or not the patient has their natural crystalline lens, does not seem to affect the final vision after RD. Ultimately, the main factors for a good vision outlook include keeping the macula attached, the detached macula being of short duration and at a low height.

The outlook for a different type of retinal detachment, called Tractional RD, is pretty variable. The final impact on vision depends on what’s causing the detachment and if there are any complications affecting the vision. Exudative RD, which is caused by the outflow of fluid from blood vessels, also has varying outlooks depending on the underlying condition.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Retinal Detachment

Proliferative retinopathy (PVR) is a condition that can happen to around 8% to 10% of patients who’ve had a repair for retinal detachment (RD). This makes it the most common reason for the repair failing. In PVR, different types of cells form layers on the outside and inside of the retina and the vitreous part of the eye. When these layers become too tight, they can cause a range of problems, including pulling loose the non-colored epithelium from the pars plana, shrinking of the retina, or creating permanent folds in the retina.

Certain factors can increase a patient’s risk of developing PVR. These include being older, having giant tears in the retina, RD affecting more than half of the eye, bleeding in the vitreous, a detachment of the choroid (the layer which supplies the outer retina with nutrients), undergoing a previous RD repair, or if they’ve received a specific cold temperature treatment called cryotherapy.

- Occurrence in 8% to 10% patients post a retinal detachment repair.

- Involves abnormal cell growth on the retina and vitreous.

- Can cause the retina to shrink or fold permanently.

- Risk factors include age, extensive retinal tears or detachment, previous RD repair, or undergoing cryotherapy.

Preventing Retinal Detachment

If individuals notice any changes in their vision, they should promptly see an eye specialist, such as an ophthalmologist or optometrist. It’s vital for them to understand that vision loss that results from a detached retina, a condition known as retinal detachment, can be permanent. If they get diagnosed with retinal detachment, they’ll most likely require surgery. Knowing about the surgical process can help to reduce worries about having the operation and may improve the patient’s commitment to treatment, leading to excellent surgical results. This knowledge is especially important after a specific type of eye surgery known as pneumatic retinopexy. This procedure requires the patient to maintain a certain position to allow a gas bubble to successfully reattach the detached retina. When a gas bubble is inside the eye, air travel should be avoided, as this can cause the gas bubble to expand, leading to a rise in eye pressure, and potentially, permanent eye damage and loss of vision.

To prevent retinal detachment, several preventative strategies can be used, including laser treatment, freezing treatment (cryotherapy), and attaching a piece of silicone to the white of the eye (scleral buckling). According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, specific eye conditions should be promptly treated. These include sudden issues related to flashes/floaters in the vision and separation of the retina at its base. Other conditions that might need treatment include trauma-related breaks in the retina. Also, in certain circumstances, individuals without symptoms might need treatment if there are no signs of a minor detachment.

In certain situations, conditions that need laser treatment include sudden problems at the edge of a weakened area of the retina (laser) and this weakening area with minor retina detachment. The decision to treat ‘lattices’ (areas of thinning in the retina) using laser should be made on a case-by-case basis, particularly in patients with only one eye, those with detachment in the other eye and in people who can’t regularly follow-up with their eye specialist. The presence of fluid around the break in the detached retina is a sign of minor detachment. However, the fluid shouldn’t reach far behind the central part of the eye for it to be classified as minor. Another definition of minor detachment is one that doesn’t affect vision or the field of view.

The use of laser to prevent retinal detachment in patients with a gap in the back part of the eye, a condition called fundal coloboma, has been debated. Still, favorable outcomes have been reported from using the preventive laser. However, using a preventive laser in patients with sudden retina destruction may not prevent the retina from detaching.