What is Retinitis?

Retinitis is a condition where the retina, the layer at the back of your eye, becomes inflamed. This part of your eye works like a camera, capturing images and sending them via the optic nerve to the brain to process. This allows us to see. Retinitis often happens in relation to other medical conditions, particularly infections or inflammatory diseases, and it can threaten your eyesight.

Many things, including infections, inflammatory diseases, and reactions to allergies, can cause inflammation in different parts of the eye. The ‘uvea’ is made up of three parts: the iris (the colored part of your eye), the ciliary body (which helps your eye focus), and the choroid (a layer of blood vessels and connective tissue between the retina and the white of your eye). Inflammation can affect any of these areas, leading to different conditions. Some examples include ‘anterior uveitis’ or ‘iritis’, where white blood cells accumulate in the front of the eye, and ‘posterior uveitis’, which affects the back of the eye, including the retina or choroid.

Infectious retinitis can be caused by viruses like human herpesvirus 5 or cytomegalovirus, parasites like ‘Toxoplasma gondii’, or fungi like ‘Candida’. There are many things that can increase your risk of developing this form of retinitis, such as an active infection during pregnancy or childbirth, living in or visiting an area where these infections are common, or having a weaker immune system. Furthermore, retinitis can appear as a result of infections in your heart valves, stomach, urinary tract, or among people who use drugs intravenously. Additionally, retinitis can sometimes be the only symptom of autoimmune diseases like Behçet’s disease.

The effects of retinitis can vary based on the patient’s age, where the infection is in the body, and the state of their immune system. Patients can have isolated retinitis or it may be associated with other conditions affecting the blood vessels in the eye, like retinochoroiditis or chorioretinitis. Doctors need to adjust their approach to treatment based on the specific cause and severity of retinitis. The goal of treatment is to prevent losing vision and to protect the other eye.

What Causes Retinitis?

Retinitis, an inflammation of the eye’s retina, can be caused by several reasons such as infections, inflammation, or genetic causes. Some people have specific genetic traits, called human leukocyte antigens (HLA), that may increase their likelihood of developing retinitis.

There’s a type of retinitis named Birdshot chorioretinitis which is usually found in people carrying a specific HLA trait (HLA-29), and it forms lesions on the retina that resemble birdshot pellets. In fact, around 45% of people with another genetic trait (HLA-B27) develop both uveitis (another type of eye inflammation), and inflammatory bowel disease. Another condition, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, also shows a strong association with certain specific genetic traits.

Infections caused by bacteria, spirals (a type of bacteria), viruses, fungi, and parasites can also cause retinitis.

Parasitic infection: Humans can get this parasite called T gondii from cats, which are the primary carriers for this intracellular organism. T gondii can cause uveitis, either as a reaction to the infection acquired at birth or as a result of a fresh infection.

Viral infections: Eye inflammation caused by Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection commonly happens in patients with weakened immune systems and can result in blindness. While it’s not usual in North America and Europe, it’s more common in Southeast Asia. Furthermore, herpes viruses such as HSV-1, HSV-2, and varicella-zoster virus (HSV-3/VZV) may cause acute retinal necrosis. An infection with the West Nile virus can result in retinal inflammation and blood vessel inflammation. Following a measles infection, some patients may develop subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, a fatal brain disease. Dengue fever can cause retinitis and inflammation of a small depression in the retina (foveolitis). Infection with the chikungunya virus can lead to various inflammatory eye symptoms.

Bacterial infections: Syphilis and tuberculosis may cause posterior uveitis. Another bacterial infection is Cat Scratch disease, where a bacteria called Bartonella henselae can cause infection following a scratch, bite from a cat, or contact with flea feces. Lyme disease, caused by a tick carrying Borrelia burgdorferi, may sometimes present as retinitis in the late stages. Patients who live in areas where the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum is common may develop a condition leading to retinitis, known as ocular histoplasmosis syndrome.

Fungal diseases: Here, the most common infection sources are Candida and Aspergillus. Histoplasma fungi may result in the aforementioned ocular histoplasmosis syndrome.

Helminthic diseases: Toxocariasis, caused by a worm called Toxocara canis, can cause retinitis in infants and young children.

In some cases, eye inflammation occurs after a person recovers from a fever due to a bacterial, viral, or protozoal infection — this is called post-fever retinitis. Generally, patients will experience these eye issues 2 to 4 weeks after the fever subsides. They may include patches of retinitis, potential optic nerve involvement, detached or swollen macula, and changes in retinal vessels.

Non-infective causes can be systemic inflammatory diseases. Conditions like Behçet disease, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, psoriatic arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, Sjögren syndrome, and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome have been associated with eye inflammation.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Retinitis

Epidemiological data can vary according to factors like the source of the health issue, the patient’s immune system, and where they live. Let’s consider a few specific examples:

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV): CMV retinitis mainly impacts people with weakened immune systems, such as newborn babies, AIDS patients, and organ transplant recipients. After stem cell transplants, about 4% of patients might develop this condition. CMV is a significant cause of eye infections in AIDS patients, especially when their CD4 T-lymphocyte counts drop very low. Medicines like antiretroviral therapy have significantly reduced cases of CMV retinitis. Generally, this condition tends to show up in people aged 20 to 50.

- Toxoplasmosis: Caused by T. gondii, this is the major causative agent of posterior uveitis in healthy people. The infection doesn’t affect 80% to 90% of those with genotype II, which is common in Europe and the US. In contrast, genotype I, predominant in Central and South America, often causes systemic symptoms. In regions with major T. gondii infection, such as Brazil, nearly 30% to 55% of posterior uveitis cases are due to toxoplasmosis.

- Human Herpes Virus (HSV): HSV leads to keratitis, a common eye disease that can cause blindness globally. Newborns with HSV keratitis might develop severe issues like corneal scarring, cataracts, and chorioretinitis. About 35% to 45% of neonatal HSV cases involve disease in the skin, eyes, or mouth.

- Behçet Disease: This disease affects men more than women and often impacts young adults. Men have a higher risk of eye issues and a worse vision prognosis. Behçet disease is most common in eastern Asia and the Mediterranean region. In the US, cases range from 0.12 to 5 per 100,000 people. Uveitis affects 60% to 80% of patients with this disease. The Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, after Behçet syndrome, is the second leading cause of uveitis in Japan.

- Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF): This is the most deadly tick-borne disease in the US, especially in the Southeast, parts of the Northeast, and Central and South America. In certain areas, such as North Carolina, about 42 children per 100,000 might get RMSF each year. Although more common in Whites, Black individuals tend to face higher fatality rates. American Indians have the highest risk, especially males between ages 5 to 9 and 60 to 69. However, the risk of posterior uveitis with RMSF is low.

- Lyme Disease: This disease is endemic in North America and Europe, accounting for 4.4% of posterior uveitis cases in a study of 160 patients.

Here’s some additional data:

- Acute retinal necrosis can affect anyone, regardless of their immune status, age, or gender, and accounts for 5.5% of uveitis cases over a decade.

- Immunocompromised patients, infants, and elderly people over 55 are at the highest risk for ocular histoplasmosis syndrome from H. capsulatum.

- Between 2% to 9% of people with inflammatory bowel disease and 7% of systemic lupus erythematosus patients may develop uveitis.

- Ocular toxocariasis mainly affects older children and teenagers.

- Approximately 1% to 2% of patients with cat scratch disease may develop neuroretinitis.

Signs and Symptoms of Retinitis

Understanding the conditions behind certain eye diseases related to inflammation is easier when you know the symptoms and characteristics of each particular disease:

Posterior uveitis usually doesn’t cause pain. Symptoms include specks floating in the vision and blurred vision.

Cytomegalovirus retinitis often affects one eye, but can spread to the other if left untreated. Symptoms can include flashes of light, a blind spot or blurred vision, besides the floaters. These symptoms are especially important in patients with AIDS to consider.

T. gondii infections often don’t show symptoms and are typically discovered during routine eye exams. When they do show symptoms, it’s usually just floaters. In addition, a distinct white appearance of the eye also known as a “headlight in the fog” is noted.

Behçet syndrome can cause repeating sores in the mouth and other areas, and various other symptoms like skin problems, digestive issues, nerve disease, vascular disease, or arthritis. Eye inflammation, specifically panuveitis, is a common sign of this disease.

Acute retinal necrosis can cause a red, painful eye in addition to those symptoms paired with retinitis. This condition forms patchy white-yellow spots that grow and blend together over time.

Neonatal ocular HSV can initially seem symptom-free. Early signs include excessive watery eyes, signs of eye pain in a child, and conjunctival redness.

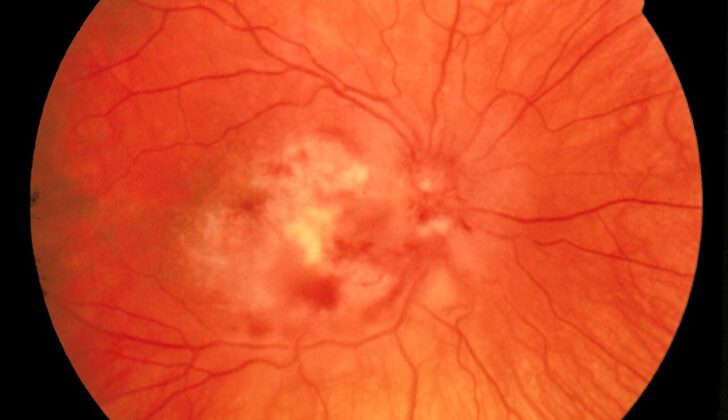

Cat scratch disease can lead to an array of symptoms from fever and unease to blurred vision. Detailed retinal examination can reveal a variety of symptoms including hemorrhages, cotton wool spots and multiple distinct lesions in the deep retina.

Syphilis can cause a variety of eye diseases from anterior and posterior uveitis, retinal vasculitis, keratitis, scleritis, or papillitis. In the later stages, syphilis can cause a Argyll Robertson pupil, which is characterized by small pupils that only respond to near stimuli.

Tuberculosis often presents yellowish nodules, tuberculomas or abscesses in the choroid part of the eye. It can also be associated with serpiginous-like choroiditis, which has two forms. One appears as a yellowish lesion that sits in the posterior pole. The other appears typically in the posterior pole and mid-periphery with multiple yellow-whitish lesions.

Other conditions such as Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Toxocariasis, Dengue Fever and Sarcoidosis also present their unique set of ocular manifestations that can be diagnosed by a medical professional.

It’s important to note the characteristics of each condition, since the symptoms may vary and must be accurately diagnosed for treatment. This list represents the most common disorders, but other conditions such as Chikungunya Fever, Endogenous Endophthalmitis, Diffuse Unilateral Subacute Neuroretinitis, West Nile Virus, Post-Fever Retinitis, Subacute Sclerosing Pancephalitis and others also present with distinct ocular profiles.

Testing for Retinitis

To evaluate retinitis (an inflammation of the retina, the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye), a detailed eye examination is carried out. This can include a slit-lamp examination (a special microscope that can look into the back of the eye), photos of the inside of the eye, and several other tests:

– Fluorescein fundus angiography (FFA): a type of photography creating a detailed image of the blood vessels inside the eye.

– Optical coherence tomography (OCT): a scan providing images of the retina’s layers.

– Ultrasound: used to check for problems such as a detached retina and evaluate any inflammation if the interior of the eye is unclear.

– Specific tests to identify bacteria, fungi, and viruses that may be causing the retinitis.

– A biopsy: taking a small sample of retinal or chorioretinal tissue for examination.

– A visual field test: assessing peripheral vision.

If underlying causes can’t be found, further tests like a chest x-ray to check for lung conditions such as sarcoidosis or tuberculosis could be required. Blood tests for syphilis may also be necessary.

The diagnosis for specific types of retinitis, such as Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Toxoplasmosis, Herpes Simplex Virus, Acute Retinal Necrosis, Behcet disease, etc., is based on thorough eye exams, detecting certain eye features, blood tests, and/or imaging. For example, diagnosing CMV retinitis doesn’t rely on CMV serology (blood tests designed to detect CMV virus), but rather on careful inspection of features in the retina. However, those with CMV retinities should also get an HIV test and maybe a CD4 count, which measures the number of specific white blood cells that fight infections in the body.

For other conditions like Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, the diagnosis is confirmed using specific blood tests. Likewise, syphilis, Lyme disease, Tuberculosis, Dengue Fever, Sarcoidosis, and Cat Scratch Disease all involve specific tests to confirm diagnosis. This could range from specific blood tests (like ELISA and Western blot tests for Lyme disease), PCR to detect viral genomes (used in Dengue Fever), or a chest x-ray followed by a detailed CT scan of the chest (used in Sarcoidosis).

Overall, making a diagnosis starts with a careful eye examination and often involves specific tests to identify the underlying cause. These tests help to ensure that the right treatment plan can be created to help manage the condition effectively.

Treatment Options for Retinitis

For posterior uveitis, a condition affecting the back of your eye, topical medications aren’t always successful. In some cases, doctors may opt for a stronger topical steroid called difluprednate to reduce inflammation. However, patients must be closely monitored, and in some cases, they may need to have the medication directly injected into or around the eye.

For more severe cases affecting both eyes or paired with glaucoma, oral medications might be necessary. In some situations, like in patients with Behçet syndrome or choroiditis (a type of eye inflammation), this systemic treatment could be needed. When these treatments aren’t successful or inflammation persists, medicines that suppress the immune system might be needed.

In conditions where the inflammation needs ongoing control, doctors might implant or inject a long-lasting medication into the eye. And to monitor the effectiveness of the treatment, regular eye examinations are needed.

For conditions like Behçet syndrome, the goal of treatment is to control inflammation, reduce the recurrence rate, and avoid complications. The primary treatment includes topical steroids and eye drops that dilate the pupil such as scopolamine or cyclopentolate. If the inflammation persists, oral medications may be necessary.

For some types of eye inflammation like acute retinal necrosis, or conditions caused by infections, a blend of antimicrobial and steroid treatments is used. In the case of infections, starting the antimicrobials first is essential to avoid severe damage to the eye.

Other conditions, like cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis, which is a serious viral infection of the eye’s retina, or toxoplasmosis, a disease usually caused by a parasite, have specific treatments. Most involve a blend of medications targeting both the condition itself and also the inflammation associated with it.

Finally, for certain other conditions like sarcoidosis, an inflammatory disease that can affect various organs, systemic treatments including oral or intravenous glucocorticoids, medications that help reduce inflammation, might be used, particularly in the early stages of ocular disease. Other medications might be considered if other treatments aren’t successful.

What else can Retinitis be?

If you have Behçet’s disease, some other health conditions might be causing your symptoms. Here are some of them:

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (an autoimmune disease)

- Reactive arthritis

- Inflammatory bowel disease (like Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis)

- Celiac disease (a gluten intolerance)

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome (a severe skin reaction)

- Pemphigoid and pemphigus (skin conditions)

- Lichen planus (skin rash)

- Linear IgA bullous dermatosis (a skin illness)

- Side effects of certain drugs (like those of methotrexate, chemotherapy agents, and nicorandil)

- Nutritional deficiencies such as lack of vitamin B12, iron, and folic acid

- Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (canker sores)

- Cyclic neutropenia (a blood disorder)

- Periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis (PFAPA) syndrome

- Hyperimmunoglobulinemia D syndrome (an immune disorder)

- A20 haploinsufficiency (a rare genetic disorder)

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections might also be confused with benign cotton wool spots or immune recovery uveitis.

Pseudotumor cerebri, a condition that increases pressure inside the skull, can mimic a quite uncommon disease – bilateral cat scratch disease.

Children with retinoblastoma and a parasitic infection called ocular toxocariasis may show symptoms of strabismus (crossed eyes), poor vision, and white discoloration in the pupil. When making a diagnosis, doctors should also think of other possible reasons like ocular toxoplasmosis and tuberculosis.

Many health issues can cause granulomatous uveitis, an eye inflammation. Here are some possible causes:

- Sarcoidosis (an inflammatory disease that usually affects the lungs)

- Candida, histoplasmosis, and cryptococcosis (types of fungal infections)

- Tuberculosis (a bacterial infection)

- Post-streptococcal infections (illnesses that occur after a Streptococcal infection)

- Multiple sclerosis (a chronic disease that affects the brain and spinal cord)

- Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease and sympathetic ophthalmia (eye disorders)

- Lymphoma (a type of cancer)

- Blau syndrome and histiocytosis (genetic disorders)

- Granuloma annulare (a skin condition)

- Lens-induced uveitis (an eye illness)

- Common variable immune deficiency (an immune disorder)

- Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (a type of arthritis that affects children)

What to expect with Retinitis

The results of visual treatments can change based on several factors, including the type of infection, the patient’s overall health, and the specific parts of the eye impacted. However, usually the outlook is positive with the right treatment. Vision loss can occur if the central point of the eye (the fovea) or the area where the optic nerve enters the eyeball (the optic disc) is affected. It can also occur due to new blood vessels growing in the eye, scarring, or eyesight damage. In some cases, a condition called Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, which is a separation of the retina caused by a break in the retina, can also lead to visual loss.

There are several conditions that carry a grim vision prognosis (outlook), some of which include:

Progressive outer retinal necrosis: This disease tends to worsen or come back, leading to poor outcomes. Most patients affected by this disease eventually experience total retinal detachments (separation of the retina from the back of the eye) and minimal-to-no light perception.

Behçet Syndrome: This disease can cause blindness if it isn’t treated.

Neonatal HSV: This is a disease found in newborns that appears harmless at first but has a high risk of spreading to the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord) if not treated.

Acute Retinal Necrosis: The visual outcomes associated with this disease are generally poor, mainly due to retinal detachment. However, it can also happen due to chronic eye inflammation, epiretinal membrane (a disease where a membrane grows on the surface of the retina), macular ischemia (a condition where the central part of the retina does not get enough blood and oxygen), and optic neuropathy (damage to the optic nerve).

Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis: This is a serious disease with a very poor outlook in terms of vision recovery.

Cat Scratch Disease: Most patients with neuroretinitis (a condition affecting the optic nerve and retina) have a good long-term prognosis. Some patients may experience leftover issues like optic disk pallor (a pale appearance of the eye’s optic disc), diminished contrast sensitivity (difficulty in seeing differences in light and dark areas), and altered color vision. Some additional complications for these patients might include macular holes (a break in the central zone of the eye’s retina) with posterior vitreous detachment (separation of the clear gel in the back part of the eyeball).

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Retinitis

Retinitis, an eye condition, can lead to several complications. These include:

- Blindness

- Damage to the retina (retinal breaks and retinal detachments)

- Damage to the optic nerve (optic neuropathy and optic atrophy)

- Macular scar formation and macular swelling (cystoid macular edema)

- Abnormal blood vessels in the eye (choroidal neovascularization)

- Development of complicated cataract

- Persistent eye inflammation (chronic vitritis)

- Macular ischemia (reduced blood flow to the macula of the eye)

- Glaucoma (increased pressure in the eye)

- Bleeding into the vitreous (vitreous hemorrhage)

- Phthisis (shrinkage of the eyeball)

These complications can affect vision and overall eye health significantly.

Preventing Retinitis

Retinitis is a group of conditions that cause inflammation in the retina, the back layer of your eye which picks up light. Different kinds of retinitis occur due to a variety of causes, such as certain viruses and parasites or inflammation-related conditions. The key symptoms can be floaters, which are little dots or lines you see drifting across your vision, or a reduction in your quality of vision.

It’s essential to recognize the signs and know about the risks of retinitis because leaving it untreated could cause irreversible damage to your vision. Therefore, it’s important to pay attention to any changes in your vision, such as new floaters or sudden flashes of light. These signs could mean your retina is inflamed.

Quick recognition and treatment of retinitis can help prevent any loss of vision and limit the impact of any complications that may be connected to retinitis. It’s particularly important for people at high risk, such as individuals with weakened immune systems or with previous experiences of eye inflammation, to have regular eye examinations.

If you have been diagnosed with retinitis, it’s crucial to stick to the treatment your doctor provides and come back for any follow-up checks to keep your retinitis managed and to limit its effect on your overall vision quality and health.