What is Rotor Syndrome (Rotor type hyperbilirubinemia)?

Rotor syndrome, also known as Rotor type hyperbilirubinemia, is a rare inherited disease that affects the liver, causing a buildup of a yellow pigment called bilirubin in the blood. This buildup can result in a condition called jaundice, where the skin and the whites of the eyes turn yellow. Bilirubin usually gets processed in the liver to be removed from the body, but in Rotor syndrome, this processing is impaired.

There are two types of hyperbilirubinemia or increased bilirubin levels in the blood associated with this condition – ‘direct’ (conjugated), which has been processed by the liver, and ‘indirect’ (unconjugated), which hasn’t. Rotor syndrome involves primarily the direct type, making up over 50% of the total bilirubin present.

Despite its symptoms, Rotor syndrome is a harmless disorder that does not progress or cause other health problems, and it doesn’t need treatment. Most people with this condition show no symptoms, and the jaundice usually gets spotted during a routine health check or other medical tests. It behaves similarly to a syndrome called Dubin-Johnson syndrome, but unlike this syndrome, the liver tissue appears normal in people with Rotor syndrome and there’s no extra pigmentation of the liver.

Also noteworthy is the difference from another condition called Gilbert syndrome, where mostly unprocessed bilirubin accumulates, unlike Rotor syndrome where it’s primarily processed bilirubin present in high amounts.

Rotor syndrome symptoms usually start appearing shortly after birth or during childhood. Jaundice may come and go, and sometimes the only sign might be yellowing of the eye corners (conjunctival icterus). This yellowing takes place due to the high bilirubin levels, presence of a compound called coproporphyrin in the urine, and reduced ability of the liver to take up certain chemicals known as anionic diagnostics, including a specific tracer used in liver imaging called cholescintigraphic tracers.

What Causes Rotor Syndrome (Rotor type hyperbilirubinemia)?

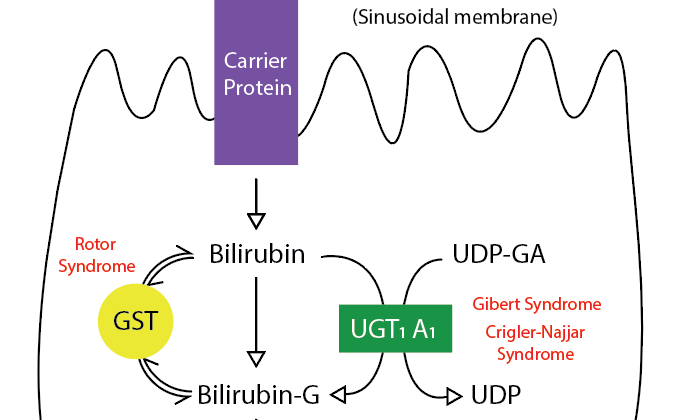

Rotor syndrome is a condition that remains somewhat mysterious, but it seems to be primarily due to a deficiency in the liver’s ability to store certain compounds known as organic anions, which include bilirubin diglucuronide. This condition is linked to a genetic disorder that is passed down through families where both sets of a certain gene pair (SLCO1B1 and SLCO1B3 found on chromosome 12) have mutations.

These genes are responsible for creating proteins called organic anion-transporting polypeptides 1B1 and 1B3 (OATP1B1 and OATP1B3). These proteins, located in liver cells, help to move various compounds into cells without requiring sodium, including hormones, drugs, toxins, and more. They are structurally quite similar and are located within the cell membrane.

In a healthy liver, most of the bilirubin (a byproduct of old red blood cells) is connected to other molecules by liver cells (hepatocytes) and then sent back out into the bloodstream. There, other hepatocytes reabsorb it via the OATP1B1 and OATP1B3 proteins.

In the case of Rotor syndrome, these proteins are abnormally short. As a result, the liver cells are less effective at taking up and removing bilirubin from the body. This causes high levels of bilirubin in both blood and urine, leading to the symptoms of jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes) and dark urine.

Rotor syndrome was found in a study of eight families to be linked with mutations in genes that are believed to affect the functioning of the above-mentioned OATP1B1 and OATP1B3 proteins. These proteins play a crucial role in the uptake and elimination of numerous drugs and their derivatives through the hepatocytes’ coating. This suggests that individuals with Rotor syndrome may be at risk for severe toxic effects when using certain medications.

Another recent study evaluated how certain gene insertions (long interspersed nuclear element-1, or LINE-1) might potentially lead to Rotor syndrome.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Rotor Syndrome (Rotor type hyperbilirubinemia)

Rotor syndrome was initially identified in 1948 by Rotor and his team in the Philippines, and since that time, cases have cropped up all over the world, including the US, Japan, France, Mexico, Papua New Guinea, and Italy. As we don’t currently know exactly how many people have this condition, we often discover it by accident while looking for other health problems. One crucial point to remember about Rotor syndrome is that it’s the second least common inherited cause of hyperbilirubinemia – a condition where there is too much bilirubin in the blood – following Crigler-Najjar type 1. Additionally, both men and women can have Rotor syndrome.

As for the age when people start seeing symptoms, it often starts to show up during the adolescent years or early adulthood, but some cases have been seen shortly after birth or during early childhood.

Signs and Symptoms of Rotor Syndrome (Rotor type hyperbilirubinemia)

Rotor syndrome often doesn’t cause any symptoms. However, some people might experience a few signs like a general yellowing of the skin (non-itchy jaundice) from birth or during early childhood. These symptoms might come and go. Some people might only notice a yellowing of the white part of their eyes (scleral icterus). Other complaints could include passing dark-colored urine, continuous jaundice, and feeling tired. Rarely, some people (about 5% to 30%) might also experience belly pain, changes in the stomach lining, and fever.

Usually when a doctor examines a person with Rotor syndrome, everything appears normal except for mild jaundice. This is caused by excess bilirubin (a substance that’s produced when red blood cells break down) giving the tissues a yellow-orange color. This is most noticeable on the white part of the eyes. Unlike other similar disorders, people with Rotor syndrome do not experience itching. Additionally, they do not have an enlarged liver or spleen, which often occurs in people with jaundice. This can help doctors distinguish Rotor syndrome from other conditions.

Rotor syndrome has specific features that make it different from similar liver disorders. For example, a condition known as Dubin-Johnson syndrome causes the liver to have a black color, but in Rotor syndrome, the liver looks normal when examined.

Testing for Rotor Syndrome (Rotor type hyperbilirubinemia)

Rotor syndrome is a condition that’s tricky to diagnose and usually only considered once other illnesses have been ruled out. One of the main clues a doctor might use to suspect Rotor syndrome is a high level of bilirubin in the blood – the substance that gives stool its brown color. Usually, this level may range from 2 to 5 mg/dL, but it can sometimes be as high as 20 mg/dL.

Other blood tests, checking for enzymes such as alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, gamma-glutamyl transferase, and alkaline phosphatase, are usually normal but they can be slightly raised. If these tests come back with very high levels, your doctor may start checking for other, potentially more serious diseases.

Even though scans and images can’t directly diagnose Rotor syndrome, they can rule out other illnesses that also cause high bilirubin levels. For example, an ultrasound scan of your liver and bile ducts could check for anything blocking the flow of bile. It’s worth noting that people with Rotor syndrome have a visible gallbladder when given a type of scan known as an oral cholecystogram, but this isn’t the case with a similar condition, Dubin-Johnson syndrome.

The most reliable way to diagnose Rotor syndrome involves analyzing a sample of urine for a substance named coproporphyrin. People with Rotor syndrome tend to have two to five times the normal level of coproporphyrin in their urine, with most of it being of a type known as coproporphyrin 1.

Both Rotor syndrome and Dubin-Johnson syndrome can cause high levels of coproporphyrin in urine. The trick is to look at the ratio of coproporphyrin 1 to another type, coproporphyrin 3. In Dubin-Johnson syndrome, around 90% is coproporphyrin 1 but the percentage is much lower in Rotor syndrome.

Another helpful test involves looking at how the body processes a substance known as bromosulfophthalein. Normally, the level of this substance should decrease after injection but in people with Rotor syndrome, this decrease is slower than normal without any secondary increase which is seen in Dubin-Johnson syndrome. Finally, a liver biopsy in Rotor syndrome does not show pigment deposition like it does in Dubin-Johnson syndrome.

Treatment Options for Rotor Syndrome (Rotor type hyperbilirubinemia)

Rotor syndrome is a harmless disease that doesn’t need any treatment. People with this condition will experience yellowish skin and eyes (jaundice), and this symptom will last their whole life. However, it doesn’t have any negative impact on their health or lifespan. Interestingly, Rotor syndrome is most often seen in people whose parents are closely related by blood. Discovering this condition could therefore help identify such close family relationships.

It’s important to recognize that Rotor syndrome is different from many severe diseases that show similar symptoms. This way, unnecessary medical testing and treatments can be avoided. Also, it’s very important to explain to patients or their family members that Rotor syndrome is a harmless condition to help ease their concerns.

What else can Rotor Syndrome (Rotor type hyperbilirubinemia) be?

Hyperbilirubinemia, or high levels of bilirubin in the blood, can be caused by many factors. These can be categorized into causing either unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia (where the bilirubin hasn’t been processed by the liver), or conjugated hyperbilirubinemia (where the processed bilirubin is unable to be removed from the body). The conditions that can lead to hyperbilirubinemia include:

- Dubin-Johnson syndrome

- Gilbert syndrome

- Crigler-Najjar syndrome

- Extra-hepatic biliary obstruction (blockage of bile flow outside the liver)

- Familial intra-hepatic cholestasis (blockages within the liver)

- Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (repeated non-dangerous blockages within the liver)

- Drug-induced hepatotoxicity (liver damage caused by drugs)

- Hemolysis (breakdown of red blood cells)

- Cholestasis of pregnancy (reduced or stopped bile flow during pregnancy)

- Viral hepatitis (liver inflammation caused by viruses)

- Autoimmune hepatitis (liver inflammation caused by the immune system attacking the liver)

- Wilson disease

- Hemochromatosis (too much iron in the body)

- Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency (shortage of a liver protein)

- Cirrhosis (scarring of the liver)

Separating Rotor syndrome from other diseases causing high bilirubin levels is crucial. Normal alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase levels can help to distinguish Rotor syndrome from disorders connected with biliary obstruction. Moreover, abnormal urinary coproporphyrin excretion and normal liver tissue can help to differentiate it from Dubin-Johnson syndrome.

What to expect with Rotor Syndrome (Rotor type hyperbilirubinemia)

Rotor syndrome is a harmless condition that lasts a person’s entire life. There are no suggested treatments for individuals struggling with Rotor syndrome because it doesn’t affect the length or quality of their life. In other words, it has a good prognosis, which means it typically doesn’t lead to any worsening conditions.

While Rotor syndrome itself carries no risk of causing illness or death, problems can arise if the person has another liver disease at the same time.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Rotor Syndrome (Rotor type hyperbilirubinemia)

Rotor syndrome is a harmless condition that doesn’t shorten a person’s lifespan. Though there’s no evidence of harmful drug reactions tied to Rotor syndrome, there may be serious liver-related issues due to the lack of two important proteins: OATP1B1 and OATP1B3. The protein OATP1B1 helps to detoxify drugs. If there’s less of this protein, certain drugs like cancer treatments, methotrexate, and statins can build up in the body and potentially lead to drug poisoning. Any medication administration involving these drugs should be done cautiously for individuals with Rotor syndrome.

Relevant Aspects:

- Harmless disease not affecting lifespan

- No harmful drug reactions reported

- Potential liver issues due to lack of certain proteins

- OATP1B1 protein and it’s role in neutralizing drugs

- Possible drug poisoning from build-up

- Need for careful drug administration

Preventing Rotor Syndrome (Rotor type hyperbilirubinemia)

There aren’t any exact instructions for patients with Rotor syndrome. However, it’s important to reassure these patients that their disease is not dangerous and the yellowing of their skin and eyes, a condition called jaundice, isn’t linked to ongoing liver damage.