What is Duodenal Ulcer?

Duodenal ulcers belong to a larger group of conditions known as peptic ulcer disease. This disease involves damage to the lining of either the stomach or the first part of the small intestine, known as the duodenum. Both the stomach and duodenal lining have a protective system made up of various layers. When there is damage to this lining that goes beyond the upper layer, an ulcer or sore forms.

Most people with duodenal ulcers feel a discomfort in their upper abdomen, a feeling often referred to as dyspepsia. However, the symptoms can vary in severity, and some may experience serious complications like bleeding from the gut, blockage in the stomach, rupturing of the ulcer, or development of an abnormal connection, called a fistula. The treatment given typically hinges on how the patient presents their symptoms and how far along the disease has progressed.

In people complaining of upper abdominal pain or discomfort, who also have a history of using certain pain medications (NSAIDs) or have been previously diagnosed with a specific stomach bacteria called Helicobacter pylori, it’s important to consider the possibility of either a duodenal or a gastric ulcer.

Anyone diagnosed with peptic ulcer disease, and especially with a duodenal ulcer, should be tested for H. pylori, as this bacteria is a common cause of these ulcers.

What Causes Duodenal Ulcer?

The main reasons for duodenal ulcers, which are sores that form in the upper part of the small intestine, are often linked to heavy or frequent use of a type of drug called NSAIDs and infection with a bacterium called H. pylori. Many people with duodenal ulcers also have the H. pylori infection. But as this infection is becoming less common, other less usual causes are becoming more common.

Other causes of duodenal ulcers are those that can damage the lining of the small intestine, just like NSAIDs and H. pylori do. These include a rare condition called Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, cancer, inadequate blood flow to the small intestine, and history of chemotherapy treatments.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Duodenal Ulcer

Research shows that duodenal ulcers affect approximately 5 to 15% of the Western population. In the past, these numbers were quite high since doctors struggled to identify and treat the bacteria, H. pylori, which often causes these ulcers. Recent research, which studied seven different scientific studies, has shown decreasing rates. However, this change varies based on factors such as how common H. pylori is in the population and the varied diagnostic guidelines used, including endoscopy.

Areas with a higher occurrence of H. pylori reported the highest numbers of duodenal ulcers. This supports previous findings that H. pylori infection can worsen the risk of developing duodenal ulcers. Another reason for the lower diagnosis rates of duodenal ulcers is that doctors and patients have become more aware of the consequences of the improper use of NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). The decreasing rates of smoking amongst youth also contributes, as research has showed smoking can also increase the risk of developing duodenal ulcers.

Signs and Symptoms of Duodenal Ulcer

People with peptic ulcer disease, specifically duodenal ulcers, can experience a range of symptoms. Many of these people, around 70%, don’t have any symptoms. However, for those who do, indigestion, or dyspepsia, is the most commonly reported complaint. A lot depends on how advanced the disease is and where the ulcer is located. For instance, pain from a duodenal ulcer usually decreases after eating, while pain from a gastric ulcer often gets worse.

- Indigestion (the most common symptom)

- Pain in the upper abdomen, which is likely to decrease after eating if it’s a duodenal ulcer or increase if it’s a gastric ulcer

- Bloating

- Nausea and vomiting

- Weight gain, because eating often eases symptoms

Some people might not seek help until they experience more severe consequences of the disease, such as an upper gastrointestinal bleed. This can result in symptoms like:

- Black, tarry stools or vomiting blood, both resulting from internal bleeding

- An increased blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level, which is a sign of kidney problems often related to bleeding

- Anemia, which could cause fatigue

More serious symptoms like anemia, black stools, or vomiting blood may suggest a serious complication like a perforation or bleeding, which would need further testing. It’s also important to keep in mind the patient’s medical history and age when considering a diagnosis.

Duodenal ulcers can occur at any age but are most common in men between 20 and 45 years old. Many affected people have a history consistent with peptic ulcer disease, like a previous diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori (the bacteria that causes most ulcers) or frequent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use.

Other pieces of information to consider include a history of smoking, daily aspirin use, and a past diagnoses of gastrointestinal cancer. During a physical examination, patients might show signs of tenderness in the upper abdomen, and if complications have occurred, signs of anemia like pale skin and a positive fecal occult blood test.

Testing for Duodenal Ulcer

If your doctor suspects that you have a Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection based on your symptoms and physical exam, they will need to conduct further tests to confirm the diagnosis. H. pylori is often associated with peptic ulcers, which are sores that develop on the lining of your stomach or the upper part of your small intestine. More specifically, it’s linked to duodenal ulcers, which are a type of peptic ulcer that occurs in the small intestine.

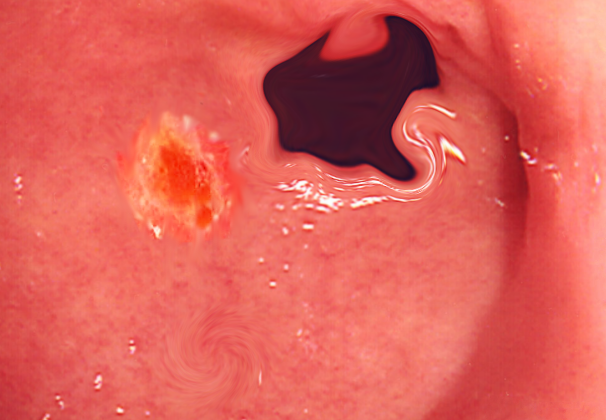

The usual way to diagnose peptic ulcer disease, including duodenal ulcers, is via upper endoscopy, which allows your doctor to directly see the ulcer. The steps they’ll take for diagnosis will depend on what tests you previously had done for your symptoms. If you’ve already had imaging tests that showed ulceration, but you aren’t showing serious symptoms associated with ulceration like a perforation or blockage, you might be treated without needing an endoscopic exam.

CT scans are occasionally used for diagnosing abdominal pain and can reveal non-perforated peptic ulcers. However, the majority of patients will probably need an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), a type of endoscopic examination. Duodenal ulcers are most often found in the first part of the small intestine (around 95% of the time), and are usually less than 1 cm across. If you can’t have an EGD due to other health issues, barium endoscopy, which uses a special type of contrast material to improve the quality of the x-ray images, is another option. Once the ulcer is confirmed, your doctor will try to determine the cause to make a treatment plan.

As H. pylori infections are often found in people with duodenal ulcers, those being evaluated for H. pylori will need further testing to definitively diagnose it. A biopsy of the tissue during EGD can help, but there are also non-invasive tests available. These include a urea breath test, a stool antigen test, and serological tests. Serological tests are less common because they can show a positive result if you’ve had an H. pylori infection in the past, even if the infection isn’t currently active. The urea breath test is very accurate but can sometimes show a false-negative result if you’re taking a certain type of medication called proton pump inhibitors (PPI). The stool antigen test is good both for diagnosing the infection and confirming that it’s been fully treated and isn’t ongoing.

Treatment Options for Duodenal Ulcer

The treatment method for duodenal ulcers (sores on the small intestine) depends on how advanced the disease is when it’s diagnosed. Some people with severe symptoms might need surgery, especially if they have complications like a perforated or bleeding ulcer. But most people are treated with medication called antisecretory agents to reduce the amount of stomach acid, which can give relief from symptoms and help the ulcer heal.

If a patient frequently uses NSAIDs (a type of painkiller), they might be asked to stop as these can cause or worsen ulcers. Quitting smoking and cutting down on alcohol is also generally advised because these habits can make symptoms worse.

Antisecretory agents come in two types: H2 receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors. The length of time a patient needs to take these medications depends on their symptoms, how well they’re likely to take their medication, and their risk of the ulcer coming back. Most people don’t need to stay on these drugs long-term after they’ve been treated for H. pylori, a bacteria that’s often found in people with duodenal ulcers.

If a patient is found to have H. pylori, they’ll be given three types of medication (two antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor) to eradicate the bacteria. A study of 24 different trials showed that getting rid of H. pylori lowered the chance of getting gastric and duodenal ulcers significantly.

Patients who have complications such as a perforation or bleeding at the time of diagnosis might need to follow recommendations made by their surgeon after surgery. They’ll likely need to stay on treatment for a longer time (8 to 12 weeks) or until it’s confirmed that the ulcer has healed by repeat endoscopy, which is a procedure that allows doctors to examine the inside of the digestive system. There are instances when patients might need a type of surgery called laparoscopic repair if their ulcers start to bleed and don’t respond to non-surgical treatment.

What else can Duodenal Ulcer be?

The type of diagnosis a healthcare provider suggests at first will probably vary depending on the initial symptoms shown by the patient. If a patient is experiencing pain in the stomach area that may change with meals, doctors might suspect that they have inflammation of the stomach lining, pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas), acid reflux disease, gallbladder inflammation, problems with the gallstones, or spasms in the gallbladder. They might even check if the patient’s symptoms could be a sign of a heart-related condition.

On the other hand, if a patient has symptoms like vomiting blood or passing black, tarry stools, this could suggest other conditions. Medical professionals might consider whether these patients have inflammation of the esophagus, a blood vessel problem, or even a type of cancer, in addition to the conditions mentioned earlier.

What to expect with Duodenal Ulcer

The outlook for duodenal ulcers, or sores in the first part of the small intestine, varies based on how serious the condition is when first diagnosed. If these ulcers are primarily caused by the use of NSAIDs, which are common types of painkillers, they can often be successfully treated by stopping the use of these drugs and starting a treatment for the symptoms. This approach typically results in high rates of recovery.

For those who have ulcers due to an infection caused by H. pylori bacteria, the treatment will target the infection. The success of the treatment largely depends on how effectively the infection is eradicated.

Patients who have severe ulcers or a perforated, or ruptured ulcer, face higher risks. These include increased chances of death and potential complications from surgery if that becomes necessary.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Duodenal Ulcer

The main problems linked with duodenal ulcers include bleeding, perforation (holes), and blockages. Most patients who have bleeding can be treated through a procedure called endoscopy. A small number of patients might need surgery if the endoscopy doesn’t work, their ulcers are big, or if they’re unstable even after resuscitation. About 2% to 10% of people with this type of ulcer disease might have holes in their guts. These patients often experience intense stomach pain which can spread across the entire belly.

Usually, these patients should consider surgical treatment. However, in rare cases, the hole may seal up on its own. Blockages are the least common complication tied to this disease. There isn’t much research available about how to diagnose and manage this issue.

Common Complications of Duodenal Ulcers:

- Bleeding

- Perforation

- Obstruction

Common Interventions:

- Endoscopic intervention

- Surgical intervention

Preventing Duodenal Ulcer

Patients who have been treated for ulcers should learn about what causes ulcers in the first place. They should also be made aware of things to avoid, like using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), as well as the risks involved with certain treatments. Additionally, if they are using proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for symptom control, they should understand the implications of using these medications over the long term.