What is Esophageal Perforation and Tears?

Esophageal perforation, or tearing of the tube known as the esophagus, is a major health challenge that requires the attention of the entire medical team. It can happen in three different parts of the esophagus, causing a range of symptoms which can vary widely. Because these symptoms aren’t always specific to esophageal perforation, diagnosis can be delayed. Even with improvements in medical technology and treatments, esophageal perforation is an immediate threat to life, with a death rate as high as 50%. It happens at a rate of 3 in every 100,000 people in the United States; tears in the chest portion of the esophagus are the most common (54%), followed by tears in the neck portion (27%), and then tears in the abdomen area (19%).

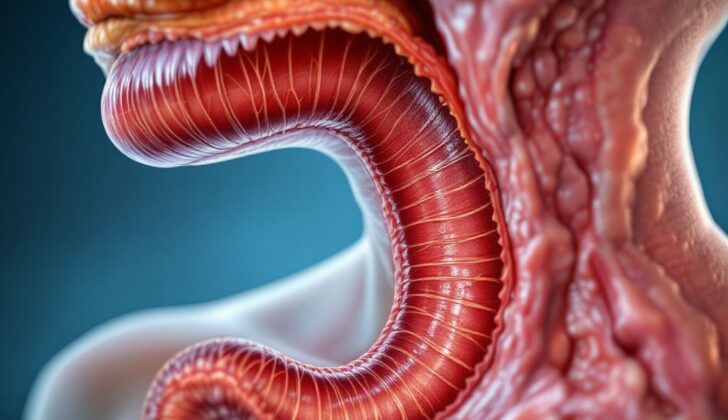

The esophagus is a fibrous, muscle-rich tube that is around 25-cm long, connecting our throats to our stomachs. It starts in the neck at a level equal to the sixth neck bone, extends through the chest, and inserts into the diaphragm, a muscular structure in our abdomen, at a level equal to the tenth back bone. It has a separate opening in the right side of the diaphragm. Along its vertical journey, the esophagus has three narrower parts:

1. The first narrow part is around 15 cm from the top teeth, where the esophagus begins at a muscle ring in the neck called the cricopharyngeal sphincter.

2. The second narrow part is around 23 cm from the top teeth, revealing the crossing point of the body’s main blood vessel and the large left lung tube.

3. The third narrow part is about 40 cm from the top teeth, where it goes through the diaphragm and forms a lower muscle ring in the esophagus.

The esophagus is divided into three parts:

1. The neck portion of the esophagus stretches from the cricopharyngeus muscle to the area above the breastbone and gets blood from the artery below the thyroid.

2. The chest portion of the esophagus, which is the longest part, ranges from above the breastbone to the diaphragm, and is supplied by lung and esophagus branches of the descending chest aorta.

3. The abdomen portion of the esophagus, the smallest part, extends from the diaphragm to the stomach’s top portion and gets blood from branches of the left phrenic and left gastric arteries.

What Causes Esophageal Perforation and Tears?

Iatrogenic perforations refer to tears or holes that occur during medical procedures, like for diagnosis or therapy. Generally, the risk of these perforations during endoscopy (a procedure where a tube with a tiny camera is inserted into your body) is quite low, though they can occur. However, the risk of perforation substantially increases with procedures such as dilation (stretching), controlling bleeding, inserting a stent, removing foreign objects, treating cancer, or certain endoscopic techniques.

Most of these perforations occur in the hypopharynx (part of the throat) or the lower part of the esophagus (the tube that connects your throat to your stomach). Miraculously, esophagus tears can also occur on their own, typically along the back and side just above where the esophagus meets the diaphragm (the muscle that helps with breathing and separates your chest from your abdomen). While these naturally occurring perforations are involving diagnostic, medical procedures, they are rare.

Spontaneous ruptures, or tears that happen on their own, are the most common cause of non-iatrogenic (not resulting from medical treatment) esophageal perforations. These usually happen due to a sudden increase in pressure inside the esophagus and negative pressure in the chest cavity. These types of tears vary in size and are more common on the left side of the body.

Esophagus injuries from trauma, like from a penetrative or blunt force, can also cause perforations although these instances are relatively rare. They can be life-threatening and often result from gunshot or stab injuries. Blunt force injuries are less common because they often accompany more severe injuries, like heart bruises or aortic dissection (tears in the main artery of the body), which can hide them.

Tears can also happen when a foreign body gets stuck in the esophagus, though these cases are also rare. When a foreign body gets lodged in the esophagus, it’s usually in the lower part and can often be due to narrowing from conditions like acid reflux (peptic strictures), esophageal muscle issues (achalasia), or inflammation (esophagitis). When something gets stuck in the middle part of the esophagus, it’s usually because of narrowing due to strictures or growths. The stuck foreign body can cause necrosis (cell death) because of increased pressure, leading to a lack of blood flow (ischemia), which can eventually result in a perforation.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Esophageal Perforation and Tears

Esophageal perforation, which is a tear in the esophagus, happens to 3 in 100,000 people in the United States. The location of these tears vary:

- 25% are found in the neck area (cervical)

- 55% occur within the chest (intrathoracic)

- 20% are in the abdomen (abdominal)

Signs and Symptoms of Esophageal Perforation and Tears

Esophageal perforations, or tears in the esophagus, can show different symptoms based on factors such as the cause and location of the tear, the level of contamination, any damage to the surrounding chest area structures, and the time passed since the perforation occurred before treatment begins. These perforations can occur in the neck (cervical), chest (intrathoracic), or belly area (intra-abdominal).

- Cervical esophageal perforations: These may cause neck pain, difficulty or pain in swallowing, and a change in the voice. A doctor may be able to feel crepitus (a crackling sensation in the neck area) or tenderness during a neck examination.

- Thoracic esophageal perforations: These cause chest pain behind the breastbone, which is often preceded by intense vomiting in patients with Boerhaave syndrome. There may also be crepitus on the chest wall due to air leaking into the surrounding tissue. Other signs include mediastinal crackling sounds heard through a stethoscope, and symptoms of fluid buildup in the lungs, such as shortness of breath, rapid breathing, a dull sound when the chest is tapped, and decreased vibration felt on the chest.

- Abdominal esophageal perforations: These cause upper belly pain that can spread up to the shoulder, and sometimes nausea or vomiting. If the esophageal tear goes through the entire thickness of the esophageal wall, it might contaminate the inner lining of the abdominal cavity causing peritonitis (inflammation).

- Later signs of mediastinitis and shock due to esophageal perforation include fever, rapid heart rate, fast breathing, low blood pressure, and blue tinted skin from lack of oxygen. These symptoms are generally considered a sign of a poor outcome.

Testing for Esophageal Perforation and Tears

Plain X-rays are beneficial in examining air that might have leaked from a ruptured esophagus. If the rupture occurs in the neck or cervical area, there might be air under the skin, called subcutaneous emphysema. If the rupture is in the chest or thoracic region, the presence of air in the mediastinum (the space between the lungs) can indicate this. Moreover, if there is any free air under the diaphragm, it shows that an abdominal part of the esophagus has ruptured. Other potential symptoms that could appear on an X-ray include fluid in the lungs (pleural effusion), fluid in the heart sac (pericardial effusion), fluid in the chest (hydrothorax), air and fluid in the chest (hydropneumothorax), and air in the tissues near the spine.

Esophagography, which is an imaging test using a contrast material to visualize the esophagus, can confirm a suspected esophageal perforation. If this contrast material spills out of the esophagus, it definitively indicates a rupture. The leakage of the contrast, or dye, can also help to identify the exact location and extent of the rupture. While studies using barium as the contrast are generally more accurate and specific, they carry a higher risk, especially due to a chemical reaction from barium called mediastinitis. As a result, water contrast studies are often favored.

A computed tomography scan, or a CT scan, of the chest and abdomen is also recommended if an esophageal perforation is suspected. CT scans can show fluid or air collections in the chest or abdomen that might need to be drained. These collections could be fluid surrounding the esophagus or air in the mediastinum.

Treatment Options for Esophageal Perforation and Tears

Esophageal perforations, or tears in the tube that connects your throat to your stomach, can be quite serious. Even with quick medical treatment, they can unfortunately lead to high mortality rates of up to 50%. Therefore, it’s extremely important that proper initial care is provided to patients with this condition.

If you arrive at the hospital with an esophageal perforation, you will likely be admitted to the ICU, especially if you are in a unstable condition or have several other health problems. Medical staff will monitor your vital signs closely and stabilize your condition. They’ll give you IV fluids and ask you to avoid eating and drinking to let your esophagus rest. Nutrition will be provided through IV as well.

Doctors will also administer antibiotics and antifungal medications through the IV to fight off any infections. They’ll use a medication called a proton pump inhibitor to decrease the production of stomach acid, which can prevent further damage to the esophagus. If there’s fluid that’s collected outside of the esophagus, a procedure might be done to drain it. Your doctors will also look at your condition to determine if surgical or non-surgical treatment is better. They may also put in a feeding J-tube, a device that allows you to receive food directly into your stomach or small intestine.

If your condition is stable, doctors may use an upper endoscopy to place a stent, a device used to keep the esophagus open and aid healing. However, this approach fails at times due to stent moving, improper placement, or inability to completely seal the damaged part of the esophagus.

If the esophageal perforations are drained well, sometimes surgery isn’t needed. However, in many cases, a surgery is required. If the perforation is caught early (within 24 hours), surgeons clean the infected area and repair the tear. Often they’ll use a flap of tissue from another part of body to support the area. However, if there’s significant tissue damage or significant leaked fluid, emergency surgery might be needed to place a stent, clean the area, or drain the fluid.

In rare cases where the patient has widespread infection or pre-existing conditions like cancer that make repair impossible, alternative procedures are used. This can involve diverting food from the esophagus, or even removing part of the esophagus. A feeding tube may be placed after these procedures to allow you to receive nutrition while avoiding oral feeding. This can particularly aid healing when there’s significant leakage outside the esophagus. However, this isn’t always necessary and depends on the surgeon’s decision. You would be allowed to eat normally again once your condition stabilizes and tests show that your esophagus is healing well without any leakage.

What else can Esophageal Perforation and Tears be?

Here are some medical conditions that may require urgent attention:

- Acute aortic dissection

- Acute coronary syndrome

- Acute pericarditis

- Aspiration pneumonitis and pneumonia

- Bacterial pneumonia

- Urgent management of pancreatitis

- Empyema and abscess pneumonia

- Mallory-Weiss tear

- Myocardial infarction (heart attack)

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Pneumothorax

- Pulmonary embolism