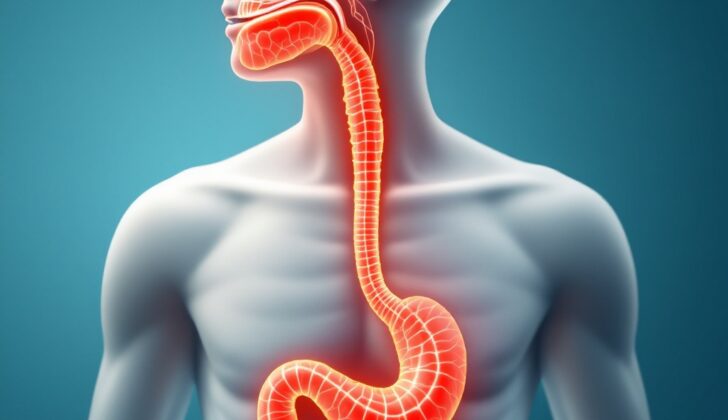

What is Esophageal Ulcer?

An esophageal ulcer refers to a clear split or gap in the lining of the esophagus, which is the tube connecting your throat and stomach. This kind of damage usually happens due to a condition called gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroesophageal reflux disease is a digestive disorder where stomach acid frequently backs up into the esophagus. Also, severe, long-lasting inflammation of the esophagus from other causes can lead to such ulcers.

What Causes Esophageal Ulcer?

Esophageal ulcers often are due to acid reflux, where stomach acid flows backward into your esophagus, or food pipe. A lot of these patients also have a condition called hiatal hernia, where a part of your stomach bulges through your diaphragm and into your chest. This is often found out through a medical procedure called endoscopy.

There’s a kind of muscle ring called the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) at the bottom of your esophagus, which usually stops stomach acid from flowing back up. But when it gets weak, stomach acid can damage the lining of the esophagus, leading to ulcers.

For some people, especially those with bulimia nervosa, frequent vomiting can cause or worsen esophageal ulcers by exposing the esophagus to stomach acid too often.

In certain situations, infections can cause inflammation of the inner lining of the esophagus. These infections, which may include Candida species, Herpes simplex, and cytomegalovirus, are often found in individuals with weak immune systems.

Some medications can cause what’s known as pill-induced esophagitis, which is inflammation of the esophagus due to the pills being in contact with it for long periods. These medications may include NSAIDs (anti-inflammatory drugs), bisphosphonates (drugs for certain bone conditions), and some antibiotics.

Frequently consuming acid-rich foods or drinks, such as caffeinated beverages or alcohol as well as habits like smoking can make esophageal ulcers worse by damaging the esophageal lining and slowing down its healing process.

Swallowing substances that can damage tissue, like certain cleaning products, or foreign objects can directly damage the lining of the esophagus. There are also cases of esophageal ulcers occurring for unknown reasons, which are called idiopathic marginal ulcers.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Esophageal Ulcer

Esophageal ulcers, which often stem from a condition called gastroesophageal reflux disease, affect about 2% to 7% of people. However, other potential causes of these ulcers have not been fully explored.

Signs and Symptoms of Esophageal Ulcer

Esophageal ulcers, often caused by GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease), usually come with a specific set of symptoms related to the esophagus and stomach. Patients might experience heartburn, the feeling of acid reflux, trouble swallowing, chest pain, a sensation of something being caught in the throat, pain while swallowing, feeling nauseous, vomiting, unusual chest pain, and even weight loss in some cases. The chest pain is usually described as a burning feeling behind the breastbone. Individuals with an active esophageal ulcer might also have symptoms such as vomiting blood, dark-colored vomit that looks like coffee grounds, chest pain that spreads to the back, and even severe circulatory shock from heavy bleeding. Difficulty swallowing, pain while swallowing, and chest pain situated behind the breastbone are common in patients with pill or infectious esophagitis.

- Heartburn

- Acid reflux feeling

- Difficulty swallowing

- Chest pain

- Sensation of something stuck in the throat

- Pain while swallowing

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Unusual chest pain

- Weight loss (in some cases)

- Chest pain spreading to the back

- Vomiting blood

- Dark-colored vomit resembling coffee grounds

- Severe shock from heavy bleeding (in extreme cases)

Testing for Esophageal Ulcer

To check for abnormal changes in the structure of the esophagus, the first test usually given is a Barium-contrast esophagram. This test involves swallowing a substance called barium, which helps to highlight the esophagus on an X-ray. If there’s an ulcer, it often appears as a round or oval shape that may be surrounded by a swollen area.

As well as this test, images can be captured using a technique called double contrast radiography. Here, tiny collections of barium can be seen near where the esophagus meets the stomach. Sometimes, these may be surrounded by a halo-like area where the lining of the esophagus is swollen.

An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is another procedure used. It allows a direct look at the esophagus, can help categorize esophageal ulcers, eliminate the possibility of cancer, and implement treatment. Herpes simplex that causes esophageal ulcers usually affects the lining of the lower part of your esophagus. On an endoscopy, they typically look like a “volcano.”

If you have an infection called cytomegalovirus (CMV), ulcers tend to appear long, wide-based, and straight. Those caused by yeast overgrowth (candida esophagitis) show up as white patches on the lining of the esophagus.

Peptic ulcers, usually as a result of acid reflux, often appear irregular or straight in shape and are more visible in the lower end of your esophagus. If a pill or medication has caused an ulcer, they are typically singular, deep, and located where swallowed substances may slow down or get stuck. Suitable examples of these would be non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID), quinidine, and potassium chloride. Remnants of the pill that caused the injury might sometimes be noticed at the injury site.

Finally, if you are diagnosed with peptic ulcers, a test for a bacteria called Helicobacter pylori should be done. This bacterium is commonly associated with stomach ulcers and can be detected through antigen testing or blood tests.

Treatment Options for Esophageal Ulcer

Identifying the exact cause of an esophageal ulcer is vital because the treatment is entirely based on addressing the root problem.

If the esophageal ulcer is due to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD, a condition where stomach acid frequently flows back into the tube connecting your mouth and stomach), the goal of the treatment is to suppress acid, control acid secretion, stimulate movement in the digestive tract (peristalsis), and enable the healing of the lining of the esophagus (mucosal wall healing). Doctors often use medications called H2 blockers, which work by reducing the amount of acid produced in the stomach. However, these medications only provide temporary relief. Common H2 blockers include cimetidine, ranitidine, famotidine, and nizatidine. Proton pump inhibitors, another type of medication used to decrease stomach acid, have demonstrated more effective long-term results in healing the ulcers faster compared to H2 blockers.

In cases where the esophageal ulcer is related to the presence of a bacteria called H. pylori, a commonly recommended treatment method is using a combination of medications for about 10 to 14 days. This could involve a treatment regime with a proton pump inhibitor, clarithromycin and amoxicillin, or a combination of bismuth subsalicylate, metronidazole, and tetracycline, or triple-therapy with lansoprazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin.

If the esophageal ulcer happens due to certain drugs, treatment would include stopping the offending medication, and introducing proton pump inhibitors to aid healing. In instances where tuberculosis bacteria caused the esophageal ulcer, a treatment plan may involve using specific medications called antituberculous for 6 to 9 months.

When the esophageal ulcer arises from an infection causing damage to the esophagus lining (infectious esophagitis), antimicrobial drugs are used. An infection caused by cytomegalovirus, a type of herpes virus, is treated with ganciclovir, while a medication called fluconazole is used for yeast infections in the esophagus (esophageal candidiasis).

Lastly, in severe situations where the esophagus becomes severely harmed, medical care may include inserting a tube through the nose into the stomach, giving fluids intravenously, administering antibiotics and pain relievers, and treating the ulcer with H2 blockers and proton pump inhibitors.

What else can Esophageal Ulcer be?

Certain symptoms may point to a variety of health issues, such as:

- Acute cholecystitis and biliary colic (conditions an inflammation of the gallbladder and severe abdominal pain respectively)

- Acute coronary syndrome (a term for conditions caused by blocked blood flow to the heart)

- Angina pectoris (chest pain or discomfort due to coronary heart disease)

- Gastrointestinal foreign bodies (any object in the stomach or intestines that’s not supposed to be there)

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (a digestive disorder affecting the ring of muscle between the esophagus and stomach)

- Myocardial infarction (a heart attack)

- Peptic ulcer disease (which causes sores in the lining of the stomach or the first part of the small intestine)

- Pulmonary embolism (a blockage in one of the pulmonary arteries in your lungs)

What to expect with Esophageal Ulcer

The outlook is generally positive for patients who consistently follow their treatment plans and eat a healthy diet. However, it’s not uncommon to see the disease return after treatment with proton pump inhibitors, a type of medication that reduces stomach acid. As a result, patients may need ongoing therapy to prevent the disease from coming back.