What is Breast Fat Necrosis?

Breast fat necrosis is the development of a firm lump in the breast caused by the death of fat cells due to injury or restricted blood supply. This damaged tissue is then replaced with scar tissue. It’s crucial to examine the patient’s history carefully as this condition can have a range of causes and implications. Distinct factors leading to breast fat necrosis include recent breast surgery, breast cancer, or physical damage to the breast. However, it can potentially resemble cancer in both its physical symptoms and its appearance in imaging scans, which can be misleading. Furthermore, it might make the breast look unattractive. In this context, we will mainly discuss breast fat necrosis in patients who had surgery.

The breast consists of three main components: skin, subcutaneous tissue (fatty layer underneath the skin), and breast tissue which includes both epithelial and stromal elements. These stromal elements, made up of fatty and fibrous connective tissue, give the breast the majority of its volume when a woman is not breastfeeding.

The primary blood supply of the breast comes from the internal mammary artery perforators. A smaller amount of blood is supplied by the lateral thoracic artery perforators. This is especially important to consider during breast reduction or reconstruction surgeries, as cutting across these vessels and reducing blood supply can lead to breast fat necrosis.

The lymphatic flow, essential for draining fluids, follows a one-way flow from deep subcutaneous and intramammary vessels towards axillary and internal mammary lymph nodes. Despite most of the blood supply coming from the internal mammary artery, only a small amount (4%) of lymph flows to internal mammary nodes. The majority (97%) goes to the axillary nodes.

Often, fat necrosis can be diagnosed by feeling a lump or mass under the breast skin or by using an imaging scan, without needing to perform a biopsy. This result is especially common among women who’ve recently had breast surgery like breast reduction, reconstruction, implant removal, or fat grafting after primary reconstruction. The lumps most often appear around the nipple area but can occur anywhere. However, if these lumps are identified through imaging and there’s no clear cause such as recent surgery or physical trauma, or if other symptoms like swollen lymph nodes or skin changes are present, it’s important to rule out the possibility of breast cancer.

What Causes Breast Fat Necrosis?

Fat necrosis, most commonly seen in the breasts, can be due to multiple causes including physical damage, certain therapies like radiation, or an infection. Risk factors that increase its likelihood include smoking, obesity, being older, and treatments related to breast cancer. It can occur after any operation on the breast, but it’s particularly concerning after a mastectomy (surgical removal of the breasts) or reconstruction, as fat necrosis can lead to changes in the breast shape or fears of cancer coming back.

The use of “free flap” technique, where tissue with its blood supply is moved from one part of the body to another, has become popular for breast reconstruction after a mastectomy. However, if blood flow to the flap is impacted in some way, the tissue can suffer and fat necrosis may occur. There are many additional factors like smoking, the choice of flap, radiation, and the surgeon’s experience which can contribute to increasing the incidence of this complication.

Breast reduction or lumpectomy (removal of part of the breast) can also lead to fat necrosis. The more tissue removed, the higher the risk. Smoking also increases the chances of this complication. In breast reduction, fat necrosis can happen in 1 to 9% of cases.

Fat grafting technique, which involves taking fat from one part of the body and moving it to the breast, can also lead to fat necrosis. After fat grafting, blood supply to the fat is random and dependent on surrounding tissues, which can cause fat necrosis. The incidence of this issue ranges between 2% and 18% with no single factor being identified as a significant predictor.

Following a mastectomy, fat necrosis can be due to small amounts of fatty tissue left without a blood supply, resulting in cell death related to lack of oxygen (ischemia). In addition to fat necrosis, other concerns following a mastectomy may include a variety of health issues such as recurrent or new cancer.

Radiation therapy also increases the risk of fat necrosis in flaps, with studies indicating that it may occur in 1 to 50% of such cases. Evidence suggests that using specific types of radiation therapy, like interstitial brachytherapy, which involves implanting radioactive material directly into the tissue, can also lead to an increased risk of fat necrosis.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Breast Fat Necrosis

Breast fat necrosis is a condition with a general occurrence rate of about 0.6%, making up approximately 2.75% of all non-cancerous breast lesions. It is found in 0.8% of breast tumors and between 1 to 9% of breast reduction surgeries. The individuals most likely to experience this condition are middle-aged women, especially those around 50 years old and women with large, sagging breasts.

Signs and Symptoms of Breast Fat Necrosis

When diagnosing breast fat necrosis, it’s crucial to take a detailed patient history. While the condition can sometimes resemble cancer, it’s important to try and avoid putting the patient through unnecessary tests or procedures, which could cause undue stress and financial strain. Some tests, like tissue sampling, can actually cause harm, especially in patients who’ve had radiation therapy for breast cancer – they could end up with a wound that doesn’t heal properly.

- History of physical injury (for example, from a car accident while wearing a seatbelt)

- Prior breast surgery or reconstruction

- Removal of a breast implant

- Previous radiation therapy to the breast

- Obesity leading to significantly large breasts

- Breasts that hang down significantly (pendulous breasts)

Upon physical examination, breast fat necrosis may present as an irregular lump in the breast that’s fixed to the skin and may cause the skin or nipple to pull inwards due to scarred tissue bands connecting the damaged area to the skin. However, these features can also indicate cancer, so it’s essential to take into account all factors related to the patient’s health.

Testing for Breast Fat Necrosis

When a surgeon discovers a lump in a patient’s breast, the main goal is to ensure it’s not breast cancer. The tests that are needed to rule out cancer can depend on the patient’s symptoms, age, and risk factors. The standard process includes a thorough examination of the breasts, a mammogram, and potentially an ultrasound or MRI. The doctor may also need to extract a small tissue sample using fine needle aspiration, a core biopsy, or an excisional biopsy.

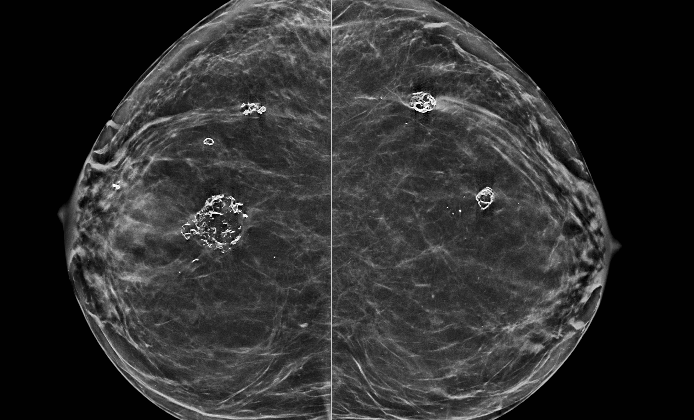

Mammograms use low-dose x-rays to examine the breasts. Fat necrosis – or damaged fatty tissue – can sometimes look like a smooth, clear lump on a mammogram. But depending on how much scarring there is, fat necrosis might appear as denser areas with tiny, irregular specks, making it difficult to tell apart from cancer.

Ultrasounds use sound waves to create images of the breasts. Fat necrosis can look like a fluid-filled cyst with bright internal lines, which can change depending on the patient’s body position. Some other ways fat necrosis might appear on an ultrasound include as bright areas in the fat under the skin, as a clear cyst with vivid imaging behind it, a darker mass with dim imaging behind it, a solid lump, or normal images. Doppler ultrasound, which shows blood flow, can help differentiate between fat necrosis and cancer by showing that the lump in question doesn’t have a blood supply. That said, mammograms are generally better at diagnosing fat necrosis than ultrasounds. Nonetheless, ultrasounds can be helpful for ruling out cancer.

MRI uses magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed pictures of the breasts. This test can be especially useful when fat necrosis is fibrotic and appears as a spiky, invasive lump with or without tiny specks of calcium. Typically, fat necrosis looks the same as surrounding fat on an MRI and doesn’t brighten after intravenous contrast is given. However, it might brighten within 6 months of surgery due to fresh granulation tissue, slightly reducing how well MRI works. In this case, fat suppression can help distinguish it from a tumor. Other signs of fat necrosis on an MRI scan include signal loss in areas with calcium and architectural distortion in scarred tissue. The most frequent finding in fat necrosis is a round or oval, low-intensity mass on images weighted by fat saturation, confirming an oil cyst is present.

Depending on the condition, mammograms, ultrasounds, and MRIs may find different results in breast necrosis. Mammograms are best for diagnosing calcium specks, ultrasounds for oil cysts, and MRI for fibrotic fat necrosis. If these tests show signs of fat necrosis, the doctor might use this information to decide if further tests are needed.

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) can reliably diagnose fat necrosis. This procedure samples cells by using a thin, hollow needle. Despite its accuracy, FNA can sometimes lead to repeated attempts due to incomplete biopsy or difficulty in sampling. If past medical history and symptoms suggest fat necrosis, FNA coupled with careful follow-up can be a valid option.

Core biopsies are typically more effective than FNA because they remove a larger amount of tissue, and their accuracy is comparable to more invasive tests. However, if images strongly suggest fat necrosis, a biopsy might not be necessary. Also, core biopsies may not always reveal cancer in high-risk patients; in these cases, an excisional biopsy might be needed.

If a biopsy does not find cancer cells, but the doctor is still unsure, the next step would be an excisional biopsy, where the whole lump and perhaps some surrounding tissue are removed.

Treatment Options for Breast Fat Necrosis

Areas of fat necrosis, or damaged fat tissue, can change over time – they might get bigger, stay the same, get smaller, or disappear entirely. Usually, they don’t require any surgical treatment. Instead, doctors will monitor them, especially if they aren’t causing pain or changing the appearance of the patient’s body. However, if the necrosis doesn’t go away on its own, or if it causes pain or alters the shape of the breast, surgical removal might be an option.

When it comes to mammograms, spots identified as “benign” or noncancerous can be monitored annually. If a spot is deemed “likely benign,” a follow-up mammogram may be recommended within six months. If a spot looks suspicious for cancer, a biopsy could be the next step.

Sometimes, fat necrosis can lead to the build-up of oily fluid which can cause discomfort. A doctor might use a needle to drain this fluid to provide relief. In cases of a solid mass or changes in the breast shape, what treatment to follow depends on the size of the spot after removal. Small spots might be treated simply with removal, or removal along with fat grafting or local tissue rearrangement. For larger areas, particularly after reconstructive surgery, more significant tissue removal and reconstruction might be necessary. These patients might choose to have additional tissue transferred from their body, use tissue expanders or implants, or undergo a procedure on the opposite breast to balance their appearance.

What else can Breast Fat Necrosis be?

The following health issues can often be confused with a condition known as breast fat necrosis:

- Breast cancer

- Tuberculosis affecting the breast

- Fibroadenoma (a common benign breast lump)

- Phyllodes tumor (a rare breast tumor)

- Breast cyst

Breast fat necrosis can look and feel a lot like breast cancer when a doctor performs an examination or looks at a scan. Thus, it’s important to get a full patient history, consider any risk factors, and take into account a patient’s age. For example, older patients (aged 40 and above), patients who previously had cancer-related surgery, and patients with a late presentation of fat necrosis are more likely to require further tests.

It’s crucial not to automatically label a case as fat necrosis just because there’s a history of trauma to the breast. This injury might be hiding or shifting attention away from an already existing lump in the breast. So, a thorough check is key.

What to expect with Breast Fat Necrosis

The primary worry when diagnosing breast fat necrosis is that it often shows symptoms and imaging results similar to breast cancer. Fortunately, breast fat necrosis is not dangerous and has a very good outlook. It does not raise the risk of developing breast cancer in the future in any form.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Breast Fat Necrosis

Damage to the fat in the breast, known as breast fat necrosis, can happen soon after a surgery or appear later. Problems resulting from this condition can range from pain and infection, to needing multiple surgeries, and even changes in the shape of the breast. These can greatly affect a patient, impacting them both physically and emotionally, and should be discussed before the surgery. Importantly, there is no known risk of this condition developing into cancer.

The complications could be:

- Pain

- Infection

- Need for multiple surgeries

- Change in the shape of the breast

- Physical and emotional impact

Preventing Breast Fat Necrosis

It’s vital to educate patients, the general public, and healthcare providers. This not only ensures the best possible results based on scientific evidence but also helps patients set realistic expectations. There are several resources available to help with this education, including:

1. The American Society of Plastic Surgeons website

2. The American College of Surgeons website

3. BreastCancer.org, which has information about Fat Necrosis in the Tissue Flap