What is Subcutaneous Emphysema?

Subcutaneous emphysema is the condition wherein air enters or forms in the layer of skin beneath the outer and middle layers, known as the subcutaneous layer. If the spread of air is limited to the subcutaneous layer and surrounding deep tissues, it’s not generally a cause for alarm. However, subcutaneous emphysema can sometimes signal that air has also entered deeper parts of the body not visible to the naked eye.

The leaking of air into other spaces in the body can lead to a variety of health problems, such as accumulation of air in the middle of the chest (pneumomediastinum), in the abdominal cavity (pneumoperitoneum), behind the peritoneum (pneumoretroperitoneum), or in the space between the lung and the chest wall (pneumothorax). The air can then travel from these parts to the head, neck, chest, and abdomen through connected tissue and anatomical planes.

Air tends to accumulate in under-tension subcutaneous areas first. However, when the pressure increases highly, air dissects along different planes, leading to widespread air spread within subcutaneous tissues, which can result in severe respiratory and cardiovascular deteriorations.

What Causes Subcutaneous Emphysema?

Subcutaneous emphysema, which is air trapped under the skin, can be caused by different factors. These include injuries to the chest area, sinuses, or face, pressure damage, ruptured bowels, or lung blisters. Medical mishaps could also lead to this condition. This could happen if a machine used to help a patient breathe malfunctions, if a safety valve isn’t properly shut, if a procedure that increase chest pressure is performed, or if there’s an injury to the air passage.

This condition can also happen if there’s a small wound in the throat or windpipe, if inflatables used to keep air tubes open in a patient’s throat are overfilled, or if pressure is applied to a closed windpipe. Damage to the food pipe during the placement of a feeding tube can also allow air to pass through.

Air can get under the skin through a wound in the throat during a tracheotomy or a wound in the chest during a shoulder surgery. It can happen through the limbs due to accidents or through ruptures in the bowels or food pipe even if there’s no lung injury. It can also happen through a cut where a chest tube was inserted or during some lung procedures.

Subcutaneous emphysema has also been seen after air is pumped into the abdomen during a minimally invasive surgery or through the female reproductive tract during a gynecological examination, after giving birth, or even during certain activities in pregnancy.

The pressure applied by a ventilator can cause the trapped gas to spread further under the skin. Non-invasive ventilation is associated with a lower risk of pressure damage, but providing manual breathing support during CPR or incorrect fitting of an oxygen mask that hinders exhalation can lead to serious consequences. In some rare cases, air trapped around the spinal cord has moved to cause subcutaneous emphysema. In one report, a patient developed a large amount of air under the skin on both sides after surgery due to severe postoperative nausea and vomiting, even without a punctured lung.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Subcutaneous Emphysema

Subcutaneous emphysema, a condition where air gets under your skin, is not a widespread condition. It usually affects around 0.43% to 2.34% of people. On average, people diagnosed with this condition are roughly 53 years old, and it’s more prevalent in males. It’s interesting to note that 77% of people who undergo certain procedures, specifically laparoscopic ones, might develop subcutaneous emphysema. However, it isn’t always noticeable.

An interesting relation was found between subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum, a condition where air gets in the space in the chest between the lungs. Pneumomediastinum occurs in 1 out of 20000 children during an asthma attack, especially those under 7 years of age. Women especially during the second stage of labor might also experience subcutaneous emphysema. The pressure increase during this stage can cause this and has been reported to happen about once in every 2000 women worldwide.

Different situations can also increase the chances of subcutaneous emphysema. For example, between 3 to 10% of people on mechanical ventilation for breathing support may experience pulmonary barotrauma, another condition closely linked with air escape. This becomes more probable depending on the reason they needed to be on a ventilator. A similar condition, tracheal injury, can occur from a rough intubation procedure, is more prevalent in women and people over 50 years of age. Furthermore, emergency intubation also increases the chance of a tracheal tear.

- Subcutaneous emphysema occurs in around 0.43% to 2.34% of people

- Most patients diagnosed with this condition are about 53 years old, and it’s seen more often in males

- About 77% of people undergoing laparoscopic procedures may develop this condition, though it’s not always noticeable

- Pneumomediastinum occurs in 1 out of 20000 children during an asthma attack

- Women during the second stage of labor might experience subcutaneous emphysema, happening in about 1 of every 2000 women worldwide

- Between 3 to 10% of people who need mechanical ventilation may have pulmonary barotrauma

- Tracheal injury is more common in women and people over 50

Signs and Symptoms of Subcutaneous Emphysema

Subcutaneous emphysema is a medical condition that needs a full patient history to understand its causes and potential complications. This condition is usually recognized in a physical examination through a symptom known as crepitus, which is a crackling sound and feeling when the affected area is palpated or touched. This can often be found in regions of the body like the abdomen, neck, chest, and face, which may present swelling or bloating. Some patients might also have changes in their voice due to vocal cord compression, or vision problems due to eyelid closure.

The presence of crepitus isn’t exclusively tied to subcutaneous emphysema; it could also indicate that air has leaked into other deeper structures or layers surrounding the lungs or heart, such as the mediastinum or pleura.

It’s important to note that severe subcutaneous emphysema can hinder normal function of the heart or lungs, which is why it’s crucial to determine its cause in each patient. While there are grading systems that evaluate the extent of subcutaneous emphysema, they’re not universally accepted or used frequently.

Additionally, certain factors may increase the risk of developing subcutaneous emphysema. For instance, patients using inhaled corticosteroids could be at a higher risk of tracheal injury due to their condition causing mucosal fragility. Therefore, it’s crucial to collect a comprehensive medication history from patients, particularly those with conditions like asthma or COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease).

Testing for Subcutaneous Emphysema

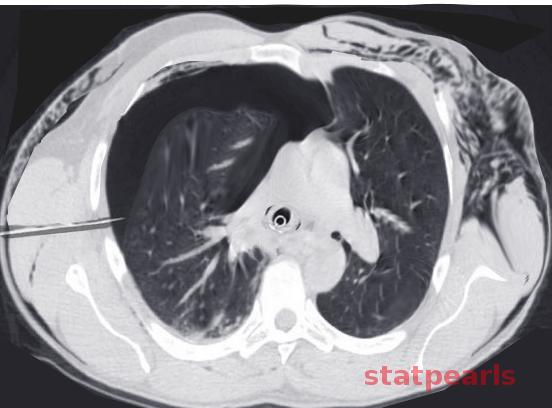

If doctors suspect subcutaneous emphysema, they can use imaging techniques like X-rays and CT scans for diagnosis. On an X-ray, irregular bright areas can be seen, giving a fluffy look along the edges of the chest and stomach walls. A specific sign resembling a ginkgo leaf might be noticed on a chest X-ray, which shows lines of gas along the chest muscle. Additionally, CT scans can show dark pockets in the under-skin layer, indicating gas. CT scans may also be able to locate the injured area causing the emphysema that might not be visible on X-rays.

If a patient develops subcutaneous emphysema in the neck or face area during the process of inserting a tube through the mouth into their airway (known as intubation), laryngoscopy should be performed before the tube’s removal. This is to check for any possible complications involving the airway or pharyngeal emphysema. If a doctor suspects that the airway was injured during intubation, bronchoscopy can be used to pinpoint the place of the tracheal injury.

Although gas can disrupt sound waves during an ultrasound, subcutaneous emphysema can still be seen as overly bright scattered specks. By applying the ultrasound probe to a section of skin without emphysema, a condition called pneumothorax (collapsed lung) can be diagnosed with 95% accuracy by identifying specific signs, including the lack of lung movement and certain patterned lines.

Treatment Options for Subcutaneous Emphysema

The first step to alleviate the condition known as subcutaneous emphysema, a condition where gas or air gets trapped under the skin, is to address the root cause. This typically results in the gradual disappearance of the condition. Mild subcutaneous emphysema that doesn’t cause significant discomfort can be managed by simply observing the patient. In some cases, abdominal binders have been used for comfort. If the underlying cause of the emphysema is controlled, the condition often improves in less than 10 days. If the patient experiences discomfort, treatment can include high-concentration oxygen, which can allow trapped gas particles to diffuse, particularly in patients who also have collapsed lung (pneumothorax) and/or air or gas in the chest that causes pressure (pneumomediastinum).

During a procedure called endotracheal intubation, damage can occur to the back of the windpipe, causing a tear. In such cases, a tracheostomy, a procedure that creates an opening in the windpipe, may be required to avoid further subcutaneous emphysema expansion or additional complications. Antibiotics can also help prevent an infection in the mediastinum, the space between the lungs. For patients on a ventilator, adjusting the amount of airflow, pressure, and minimizing air trapping, can aid in stopping progression of the emphysema and promoting reabsorption of the trapped air.

During laparoscopic procedures, where surgery is performed through small incisions, the gas used for the procedure can sometimes escape into the skin layers. Therefore, after such procedures, careful airway assessments are important. If a patient develops subcutaneous emphysema, reintubation or delayed removal of the breathing tube might be necessary. Treating the respiratory acidosis, a condition that causes too much CO2 in the blood, that can result from gas absorption, is also crucial.

For severe cases of subcutaneous emphysema, small incisions beneath the collarbone can help reduce further trapping of air. In one case, a drain was placed on the skin over the chest muscle to alleviate extensive emphysema successfully following a procedure to drain fluid from the pleural space, the space between the lungs and chest wall. However, these more invasive treatments are typically reserved for situations where the emphysema is impacting the airway or heart function.

What else can Subcutaneous Emphysema be?

In some rare cases, a condition known as subcutaneous emphysema — where air gets into tissues under the skin — has been confused with allergies and a swelling condition called angioedema. This usually happens when a patient comes into the hospital having trouble breathing and with a swollen face. The way to tell the difference between these is through a physical checkup: subcutaneous emphysema usually doesn’t cause the lips to swell.

While this condition by itself typically isn’t an immediate threat to life, it can hint at other conditions that could be very dangerous. These include a tear in the esophagus, air in the space around the lungs (pneumothorax), perforations in the trachea, bowel or diaphragm, and severe infections.

Another important point is not to automatically assume that the subcutaneous emphysema is due to an injury to the air sacs in the lungs after one has been put on a ventilator (a process called intubation). It’s also necessary to check for possible tears in the trachea that might have been caused by the intubation procedure.

What to expect with Subcutaneous Emphysema

Subcutaneous emphysema, or air trapped under the skin, is typically not life-threatening and will heal on its own. Even when a patient is using a ventilator, subcutaneous emphysema is generally not dangerous and doesn’t require any adjustment to the ventilator settings.

However, if the trapped air spreads quickly or in large amounts, it can become a serious problem. Severe subcutaneous emphysema can lead to complications such as compartment syndrome (a painful condition caused by pressure build-up), hindered chest expansion, throat compression, and tissue death. Without medical intervention, these complications can affect the patient’s respiratory and cardiovascular functions.

The speed and extent of the air expansion can also be increased with the use of nitrous oxide and positive pressure ventilation. This can worsen the patient’s condition and could potentially increase the chances of health complications and death.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Subcutaneous Emphysema

When air expands too tightly and widely beneath the skin, it could prevent the chest from expanding as needed for proper breathing. This could lead to low oxygen levels, breathing problems, and even fatal heart failure. If this expansion of air extends to the neck, it could cause difficulty swallowing and potentially close off the airway.

Patients being helped to breathe with a ventilator could face additional problems if the machine cannot provide enough air volume. This could lead to excessive pressure and possible lung trauma or worsening of air-filled pockets in the chest. If these air pockets block the chest’s outlet, air flow could be restricted. This affects the heart’s ability to do its job and can lead to poor blood flow to the brain.

The expansion of air beneath the skin can also result in other complications. For instance, if it expands into the genital area, it can interrupt the small blood vessels in these areas and cause skin death. For people with pacemakers, it could cause the device to work improperly due to trapped air within the pulse creator.

Affected Areas and Results:

- Chest expansion: Low oxygen levels, breathing problems, possible heart failure

- Neck expansion: Difficulty swallowing, airway blockage

- Lung trauma or worsening of air-filled pockets in the chest due to ventilator support

- Chest outlet obstruction: Restricted air flow, heart complication, poor brain blood flow

- Genital expansion: Interrupted blood flow, skin death

- Pacemaker interference: Device dysfunction

Preventing Subcutaneous Emphysema

For patients experiencing a mild case of subcutaneous emphysema (air trapped under the skin), understanding what’s happening can offer significant relief. They should know that the air might cause discomfort and strange sounds when the skin is touched, but this is a harmless process that will get better soon. If their eyelid swells up and affects their vision (a condition known as palpebral closure), explaining that this is a temporary situation can help ease their worries. On the other hand, in severe cases of subcutaneous emphysema, discussing ways to release the trapped air and possible outcomes helps the patient make wise decisions about their treatment.

Moreover, when patients are being prepared for general anesthesia, they should be informed about the risk of developing subcutaneous emphysema. This knowledge helps them understand what to expect, and how any emergent subcutaneous emphysema might be managed post-surgery.