What is Bacterial Endocarditis?

Bacterial endocarditis is an infection that targets the interior lining of the heart, known as the endocardium. This infection commonly affects the heart valves, but it may also happen on the endocardium or devices implanted within the heart.

There are two kinds of this infection:

* Acute endocarditis is a type of feverish illness that rapidly harms heart structures and spreads via the bloodstream. It can lead to death within weeks if not properly treated.

* On the other hand, subacute endocarditis progresses at a slower pace. It can persist for several weeks or even months, gradually getting worse. Major complications can occur if there’s a significant blockage event or a ruptured structure.

What Causes Bacterial Endocarditis?

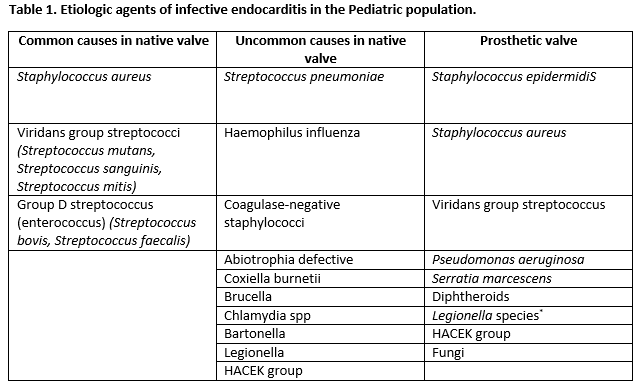

Most instances are due to certain types of bacteria including viridans streptococci, Streptococcus gallolyticus, Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci, as well as HACEK organisms, which include Haemophilus, Aggregatibacter, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella, and Kingella. Enterococci are also common culprits. Less commonly, pneumococci, a type of yeast called Candida, gram-negative bacteria, and a mix of different microbes can be responsible.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Bacterial Endocarditis

In developed countries, endocarditis is a disease that affects between 2.6 to 7 people out of every 100,000 every year. The average age of people who get endocarditis is 58.

There are several risk factors associated with developing endocarditis:

- Being older than 60 years of age

- Being male

- Using injection drugs

- Having had infective endocarditis in the past

- Having poor dental health or undergoing dental procedures

- Having a prosthetic valve or device inside the heart

- Having a history of heart valve disease – such as rheumatic heart disease, mitral valve prolapse, aortic valve disease, mitral regurgitation, and more

- Having congenital heart disease – such as aortic stenosis, bicuspid aortic valve, pulmonary stenosis, ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, coarctation of the aorta, and tetralogy of Fallot

- Having a catheter inserted in a vein

- Being immunosuppressed

- Being a patient on hemodialysis

Signs and Symptoms of Bacterial Endocarditis

The most common symptom is a fever, which may be accompanied by chills, night sweats, loss of appetite, weight loss, general discomfort, headaches, muscle aches, joint aches, stomach pain, shortness of breath, cough, and chest pain. Heart murmurs are also frequently observed – these can be heard in about 85% of patients. Around 30 to 40% of patients may also develop congestive heart failure due to issues with the heart valves. Other symptoms include skin signs like small, red or purple spots (petechiae) or red-brown stripes under the nails (splinter hemorrhages).

More serious complications may develop, such as:

- Conduction disease, which is a type of heart rhythm problem. This can include first-degree atrioventricular block, bundle branch block, or complete heart block

- Ischemia, where blood supply to the heart is cut off due to clots that have traveled to the coronary arteries. This can lead to heart attacks.

- Stroke, caused by a clot blocking blood flow to the brain

- Intracerebral hemorrhage, which is a type of stroke caused by a ruptured blood vessel in the brain

- Brain abscess, a pocket of infection in the brain

- Septic emboli leading to tissue death (infarction) in the kidneys, spleen, lungs and other organs

- Spread of the infection to the bones (vertebral osteomyelitis), joints (septic arthritis), or the psoas muscle, which is located in the lower back (psoas abscess)

- Glomerulonephritis, a type of kidney disease caused by an overactive immune response

This is not an exhaustive list of all possible complications, and some complications may be more likely in certain patients than in others.

Testing for Bacterial Endocarditis

The presence of endocarditis, or an infection of the heart’s inner layer, has definite, possible, and rejected classifications. A definite diagnosis is made based on either pathologic lesions like infected growths within the heart or specific clinical criteria. The latter can include elements such as positive blood cultures and evidence of inner heart involvement. In contrast, a possible diagnosis involves meeting fewer clinical requirements.

A diagnosis of endocarditis may be rejected if another diagnosis is confirmed, if symptoms are significantly reduced after a short course of antibiotics, or if the clinical and pathological evidence does not support it.

Major clinical evidence involves positive blood cultures and clear signs of infection inside the heart. Blood cultures need to show certain specific microorganisms responsible for endocarditis, or they need to consistently indicate such infection. Regarding the heart, things like unusual images of masses observed via echocardiography, or establishment of a new heart valve issue can signal endocarditis.

Minor clinical signs involve predisposing factors like being an intravenous drug user or having specific heart conditions. Having a fever, evidence of vascular issues, immune system responses, or laboratory evidence of endocarditis-risky organisms can also be minor indicators.

Blood cultures are typically taken at least three times before the administration of antibiotic therapy, and if results are undetermined after a few days, additional cultures can be utilized. In some cases, blood cultures might not uncover the cause of endocarditis due to prior antibiotics use or the presence of specific organisms.

Echocardiography, an imaging test of the heart, is generally used for all suspected endocarditis cases. While a transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is usually the first-line diagnostic test, a transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is more sensitive and better at identifying heart complications. In cases of high clinical suspicion but a negative initial TEE, a repeat TEE is recommended between 7 and 10 days later.

Laboratory signs of endocarditis are often nonspecific but may include elevated inflammation markers, a type of anemia, positive rheumatoid factor, and certain abnormalities in the urine.

Treatment Options for Bacterial Endocarditis

When treating a patient with suspected valve infection, antibiotics are first given to broadly cover a range of bacteria. These antibiotics will typically include vancomycin and gentamicin, to help tackle common bacteria such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus amongst others, before the results of blood tests can identify the exact bacteria causing the infection.

The duration of treatment depends on the bacteria causing the infection and the area of the heart valve affected. Treatment usually starts from first day of obtaining negative blood culture results, which mean the antibiotics have started to defeat the infection. This treatment often needs to be administered directly into the bloodstream (parenterally) for about six weeks.

If after this initial treatment, the infection returns (relapses), the patient will likely need another course of antibiotics.

Different bacteria will require different antibiotic treatments. Some common examples include:

- For Methicillin-sensitive S. aureus: nafcillin or oxacillin will be used. If the patient is allergic to penicillin but not severely so, cefazolin can be used. If there is a severe penicillin allergy, vancomycin and daptomycin are the preferred choice.

- For Methicillin-resistant S. aureus or coagulase-negative staphylococci, vancomycin is used typically for six weeks.

- For Strep bacteria like Viridans streptococci and S. gallolyticus, penicillin G or ceftriaxone will be given for a month. If these bacteria are resistant to penicillin, a combination of penicillin G and gentamicin is used. If the patient is allergic to penicillin, vancomycin is given.

- For S. pneumoniae: penicillin G, cefazolin, or ceftriaxone is given for four weeks. If the patient is allergic to penicillin, vancomycin is given instead.

- For Enterococcus, penicillin or ampicillin is given in combination with gentamicin. If these bacteria are resistant to vancomycin, other antibiotics like linezolid or quinupristin-dalfopristin or imipenem may be used.

- For HACEK organisms, ceftriaxone, ampicillin or ciprofloxacin is given for about a month.

This guideline might require adjustment since the choice of antibiotic can be influenced by local drug resistance patterns and individual patient factors.

What else can Bacterial Endocarditis be?

- Antiphospholipid syndrome – a disorder that involves the immune system attacking normal cells by mistake, leading to blood clots.

- Atrial myxoma – a rare type of heart tumor, that grows in the upper left or right side of the heart.

- Connective tissue disease – a group of disorders that affect the tissues that support, bind or separate other tissues and organs.

- Fever of unknown origin – a term used when a person has a high temperature, but the cause is not known.

- Infective endocarditis – an infection in the lining of the heart’s chambers or valves.

- Intraabdominal infections – infections that occur within the abdomen.

- Lyme disease – an infectious disease caused by the bite of a tick carrying the Borrelia bacterium.

- Marantic endocarditis – a condition where non-cancerous clots form on heart valves, often linked with severe illnesses or cancer.

- Physical medicine and rehabilitation for systemic lupus erythematosus – a collection of treatments used to manage systemic lupus erythematosus, an autoimmune disease causing your immune system to attack your own tissues and organs.

- Polymyalgia rheumatica – an inflammatory disorder causing muscle pain and stiffness in various parts of the body.