What is Streptococcus Group B?

Streptococcus agalactiae, also known as group B streptococcus or GBS, is a type of bacteria. The name ‘group B streptococcus’ comes from a classification system that groups bacteria based on specific features of their cell walls. GBS is often found in the genital and gastrointestinal areas of the body. If GBS is present in pregnant women, it can greatly increase the risk of infection in newborns and infants.

By screening pregnant women for GBS during the third trimester and giving antibiotics to those who test positive, the chances of the infection affecting newborns has been significantly reduced. In the early 1990s, around 1.7 in every 1000 newborns born were affected, compared to just 0.22 in 1000 by 2017. The prevention measures have saved nearly $294 million in medical costs every year which would have been spent managing this infection in newborns. This particular type of infection and its effects will be discussed further for different groups such as newborns, infants, pregnant women, and older adults.

The first time GBS was identified was in 1887 by Edmond Nocard when he traced it as the cause of a disease in cows that stopped milk production. Decades later, it was found to cause infections in humans as well, especially in pregnant women and newborns. The seriousness of this bacteria wasn’t fully understood until 1938 when it was linked to three cases of fatal infections in women after giving birth. Throughout the 1970s, neonatal infections caused by GBS became more prominent, and it was found to be the main cause of blood poisoning (bacteremia) and inflammation of the brain (meningitis) in newborns and infants under three months old. In rare cases, GBS can also cause infections in women after childbirth and in people with weakened immune systems, where it can cause blood poisoning or pneumonia.

What Causes Streptococcus Group B?

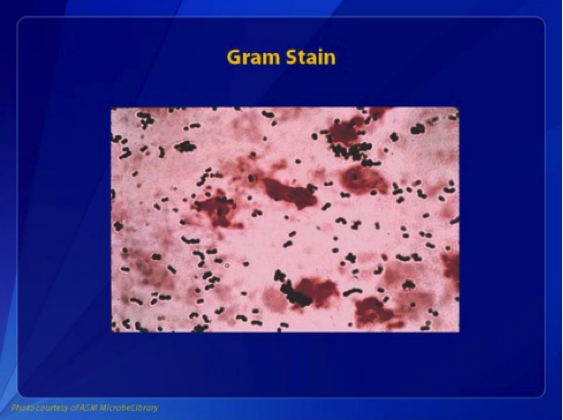

GBS, or Group B Streptococcus, is a type of bacteria. Under a microscope, it appears in pairs or chains and is colored gram-positive. If the bacteria is allowed to grow on a special plate called blood agar, it forms small, colorless colonies and destroys red blood cells, a process known as beta-hemolysis. This is due to a toxin GBS makes called the S agalactiae.

All GBS bacteria have a specific cell wall carbohydrate antigen, but they can be classified into types Ia, Ib, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, and IX, because they have different types of surface capsular polysaccharides. Some strains also produce a protein known as C protein with components alpha and beta. GBS can also develop a structure called a pilus, which helps it stick to surfaces in the body. Certain types of GBS are extremely harmful, or hypervirulent, because they have a preference for the membranes around the brain.

GBS has various uses tricks to survive in the host body and avoid detection from the immune system. It is encapsulated by a layer rich in sialic acid, a substance also found in human cells. This can trick a newborn’s inexperienced immune system into thinking the GBS is part of the body, allowing the bacteria to survive. Furthermore, GBS has hair-like structures, known as pili, that help it attach to host cells. It also makes a toxin that destroys red blood cells and creates damage in the host’s body.

On top of that, GBS creates an enzyme that interferes with the host’s immune system, making it harder for the immune cells to gather at the infection site to fight off the bacteria. GBS could be found in the normal flora of the gut and genitourinary system in up to a third of healthy women who do not show any symptoms. There are factors that can increase the risk of having GBS. This includes being of Black race, being obese, having multiple sexual partners, using tampons or those who seldom wash their hands.

Pregnant women with GBS can pass the bacteria to their newborns during childbirth. This usually happens when the water bag breaks or during a vaginal delivery. Studies have also shown that GBS can be spread from person to person and possibly through the fecal-oral route. The exact way how late-onset disease transmit, whether through external source such as breast milk or established colonization is still unclear.

Those with a weakened immune system, such as pregnant women or people with cancer, diabetes or HIV, are at risk for severe GBS infection. Those without a functioning spleen, including people with sickle cell disease, are also at risk as the spleen plays an important role in fighting these type of bacteria.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Streptococcus Group B

Neonates, or newborn babies, can become infected or colonized by bacteria, and this is often linked to whether their mother was carrying the same bacteria at the time of delivery. Around 41% to 72% of cases see the bacteria transferred from a colonized mother to their newborn baby. But surprisingly, in around 1% to 12% of cases, babies that are colonized at birth are born to mothers who do not carry the bacteria.

If the mother has a high level of bacteria in her genital tract (more than 10 colony-forming units per milliliter), the chances of the baby becoming heavily colonized and developing the GBS disease are significantly increased.

Before the use of preventative antibiotics during labor became widespread, early-onset neonatal GBS infections were considerably more prevalent, with rates between 1.8 and 4.0 per 1000 live births. Early-onset disease, which is characterized by symptoms appearing within the first six days of life, used to be responsible for about 7600 cases per year. However, thanks to guidelines implemented in 2002 that recommend universal screening for pregnant women at 35 to 37 weeks gestation and the use of prophylactic antibiotics for women who carry the bacteria, the incidence of early-onset disease has dramatically decreased by nearly 85% since 1990.

Despite these preventative measures, however, the incidence of late-onset disease (symptoms appearing from day 7 through day 89 of life) has not changed significantly, remaining at approximately 0.27 per 1000 live births. Late, late-onset GBS disease occurs in infants older than 3 months and accounts for 7% to 13% of childhood GBS infections. Infants affected are typically born prior to 34 weeks gestation or have an underlying immunodeficiency or simultaneous infection with HIV.

Over the past 20 years, we’ve also seen a 2-fold to 4-fold increase in the incidence of GBS disease in nonpregnant adults, particularly in those with underlying health conditions or who are 65 years of age or older. Residents of nursing homes are much more likely to get invasive group B streptococcus disease than those living in the broader community.

Signs and Symptoms of Streptococcus Group B

Group B Streptococcus, or GBS, has been the main source of newborn sepsis since the 1970s. Infections caused by GBS are categorized into three groups depending on when they appear. These are early-onset, late-onset, and very late-onset:

- Early-onset disease is diagnosed within the first six days of life, with most babies showing symptoms within the first 24 hours. Infected infants might suffer from breathing difficulties (like fast breathing or pauses in breathing), bluish skin coloring, sleepiness, feeding problems, an enlarged abdomen, pale skin, yellow skin and eyes, fast heartbeat, and low blood pressure. While full-term newborns often have high body temperature, preterm babies might not have a fever or could even have a low body temperature.

About 80% of early-onset GBS cases are blood infections. Lung and brain infections are less common, accounting for 15% and 5-10% of the cases respectively. Late-onset disease, which refers to GBS infections occurring from day 7 to day 89 of life, often has similar symptoms as early-onset disease. With late-onset disease though, up to 30% of the cases may be brain infections.

Late-onset disease might present with unusual bacterial infections in the bones, joints, and skin and lymph nodes. The top part of the arm is the most common site affected in infants with bone infections, while bacterial joint infections typically affect the hip and/or knee. GBS skin and lymph node infection mainly affects one side of the face or below the lower jaw, but can also be located in the groin, scrotum, or in front of the knee. Symptoms include swelling of the affected skin and enlarged lymph nodes nearby.

Very late-onset GBS disease, defined as GBS infection in infants 3 months old or older, often occurs in premature infants or those with very low birth weights. It also occurs in full-term infants with HIV or weakened immune systems. The symptoms in these older infants are similar to late-onset infection, with blood and brain infections being most common.

GBS can also cause severe illness in adults, particularly those over 65, Black individuals, and those with diabetes. Most adults affected have comorbid conditions, with diabetes, heart disease, and cancer being the most common. Common symptoms include fever, shivering, and mental confusion. Quite a few adult infections are associated with pregnancy. GBS is responsible for 15% of endometritis (inflammation of the inner lining of the uterus) during childbirth, 15% of blood infections during pregnancy, and 15% of skin infections after cesarean sections. Other infections that GBS can cause in adults include pneumonia, heart valve infection, skin infection, and bone infection. About 4% of adults who survive a first episode of GBS blood infection have a second episode within a year.

Testing for Streptococcus Group B

In simple terms, early-onset meningitis refers to the inflammation of the protective layers around the brain and spinal cord in newborns, and it presents almost identical symptoms to blood infections with no specific location. It’s critical to note here that blood tests alone can miss out on diagnosing meningitis in as many as 30% cases. So, your doctor might perform a lumbar puncture (a procedure where a needle sits between the bones in your lower spine to collect fluid) to check for the disease, even if there’s another evident source of infection.

There are numerous ways to test for this infection but relying on swift antigen detection methods (which examine for certain proteins associated with the infection) may not be entirely accurate substitutes for blood or fluid cultures (a process of growing bacteria from the suspected infection site in the lab). Furthermore, repeating these antigen tests isn’t usually suggested during the course of treatment.

In one small study, scientists found they could also use a technique called real-time polymerase chain reaction (a method to replicate and detect specific DNA), to identify the infectious agent in blood samples of 8 babies, all of whom were proven to have this specific type of blood infection via a culture test. However, this approach requires further comprehensive investigations to confirm its reliability and accuracy.

The most reliable way to diagnose an infection with group B Streptococcus (the bacteria causing the disease we’re discussing) is by growing the bacteria from a sample taken from a generally sterile area of your body in a lab experiment. This significant test helps confirm the presence of the disease.

Treatment Options for Streptococcus Group B

If your newborn is suspected to have neonatal sepsis, a serious and life-threatening infection, doctors usually start treatment with two antibiotics, ampicillin and gentamicin. The reason for this combination is that together, they work better to kill the bacteria group B Streptococcus (GBS), a common cause of neonatal sepsis, than either of them would alone. If it’s confirmed that GBS is responsible for the infection, and the baby’s condition is improving, they would then typically continue on penicillin G alone.

For newborns with GBS meningitis, a severe infection that affects the brain and spinal cord, doctors will usually check your baby’s cerebrospinal fluid (a fluid found in your baby’s brain and spine) a day or two after starting treatment to ensure the antibiotics are working. If these tests show no bacteria, the treatment could be completed with penicillin G alone for at least 14 days. If the infection persists in the cerebrospinal fluid, doctors may need to extend the treatment and conduct further diagnostic evaluations. Technology like neuroimaging can help spot complications such as unresolved infection in the brain or inflammation of the ventricles (fluid-filled spaces in the brain), and even rare cases like brain abscesses or other complications that can affect your baby’s prognosis.

If infants are diagnosed with bacteremia, a condition wherein bacteria enters the bloodstream without a known infection site, they usually receive a course of antibiotic treatment through an IV for ten days. Prolonged treatment is necessary for patients with more severe infections such as septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, or endocarditis, which affect the joints, bones, or heart respectively.

Relapses of GBS infection in newborns are rare but may occur due to various reasons like inadequate treatment, reinfection with another strain of bacteria, other underlying illnesses, or specific deficiencies in the immune system. Although antibiotics are generally effective in treating GBS infections, it’s important to note that they may not always eradicate the bacteria from the body completely. If the cause for recurring infection remains unclear, doctors may consider additional treatment options like rifampin, an antibiotic, which has shown promise in eradicating the GBS bacteria in some studies.

Pregnant mothers can take measures to prevent neonatal sepsis caused by GBS. If a mother’s GBS screening test at 35-37 weeks of gestation is positive, medical professionals usually recommend antibiotic prophylaxis. This refers to preventive antibiotic treatment that is given if there is a history of a baby having contracted the GBS bacteria, preterm delivery, prolonged rupture of membranes, high fever during labor, or certain positive test results. Penicillin is often the preferred antibiotic to prevent early-onset GBS disease.

For women allergic to penicillin, other antibiotics like cefazolin, clindamycin, or vancomycin may be recommended for preventing GBS infection. However, it’s important to note that the effectiveness of clindamycin and vancomycin in preventing early-onset GBS neonatal infection has not been completely evaluated yet.

What else can Streptococcus Group B be?

: The symptoms of early-onset Group B Strep (GBS) disease can mimic those of other bacterial infections in newborns, making it hard to diagnose. Other bacterial causes for similar symptoms can include:

- Various bacteria in the Enterobacteriaceae family

- Listeria bacteria

Often, newborns with this condition show signs of trouble breathing. However, other non-infectious health conditions can also cause the same symptoms. These can include:

- Respiratory Distress Syndrome, a breathing issue common in premature babies

- Transient Tachypnea of the Newborn, a temporary fast breathing condition in newborns

- Aspiration of meconium, a situation where a newborn inhales a mixture of meconium and amniotic fluid into their lungs at birth

In older babies, diagnosing GBS disease can depend on the specific symptoms they’re showing. For instance, meningitis in babies around this age could be due to this infection. However, it could also result from other bacteria, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, Listeria monocytogenes, or Haemophilus influenzae. It could more likely be due to various viruses. Similarly, signs of osteomyelitis, a bone infection, could be mistaken for a neuromuscular disease or Erb’s palsy when a baby doesn’t want to move their arm.

What to expect with Streptococcus Group B

The outcome of Group B Streptococcus (GBS) disease, a type of bacterial infection, often depends on how severe and where the infection is located in the body. Mortality rates can still be high, ranging from 3% to 10% for early-onset disease (occurring shortly after birth) and 1% to 6% for late-onset disease (occurring after the first week of life). Preterm infants (those born before 37 weeks of pregnancy) with early-onset disease face the highest mortality rate of about 20%.

We don’t have a lot of information about the long-term effects on patients with GBS sepsis (a severe blood infection) who don’t have meningitis (an infection of the brain and spinal cord coverings). But we do know that in infants experiencing septic shock (a life-threatening condition in response to the infection), the occurrence of periventricular leukomalacia (brain ‘softening’ due to lack of oxygen or blood flow) is connected to developmental problems later.

Despite better prevention steps, early detection, and improved patient care for GBS meningitis, the neurological outcome remains the same. Around 20% to 30% of infants with early- or late-onset meningitis might develop permanent serious neurological problems like being unable to see, hearing loss, cerebral palsy, or severe motor deficits. About 25% of these patients might experience mild to moderate problems like hydrocephalus (a condition with extra fluid in the brain), requiring surgery (a ventriculoperitoneal shunt), seizures, or minor developmental and learning delays. Only 51% of patients showed normal development for their age.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Streptococcus Group B

As stated earlier, infants can deal with dangerous complications from a GBS infection, such as GBS bacteremia, pneumonia or meningitis. Pregnant women are commonly affected by urinary tract infections, chorioamnionitis, endometritis, or severe infection of the blood called sepsis due to GBS disease.

Common Complications of GBS Infection:

- GBS bacteremia in infants

- Pneumonia in infants

- Meningitis in infants

- Urinary tract infections in pregnant women

- Chorioamnionitis in pregnant women

- Endometritis in pregnant women

- Sepsis in pregnant women

Preventing Streptococcus Group B

GBS, or Group B Streptococcus, is a type of bacteria that can naturally live in the digestive system and genital area in about 35% of healthy women. Even though most carriers of this bacteria don’t show any symptoms, some women can get sick when the bacteria spreads in their body. This can be particularly serious in pregnant women, and life-threatening for both the mother and the child. In pregnant women, GBS disease can lead to urinary infections, infection in the fluid surrounding the baby in the womb (amniotic fluid), or infection in the womb after childbirth. In some cases, it can even cause early birth or loss of pregnancy.

The bacteria can also be passed from a mother to her newborn child, which can cause severe illness in the child. Although most babies who are infected with GBS start showing symptoms right after birth, in some cases, symptoms may appear months after the child is born. These symptoms may include difficulties in breathing, making grunting noises, becoming excessively fussy or sleepy, problems with feeding, having unusually low or high body temperatures, low blood pressure or even seizures.

To protect newborns from getting sick from GBS, it is recommended that all pregnant women get tested for the bacteria as part of their routines check-ups late in their pregnancy (usually between weeks 35 and 37). If a soon-to-be mother tests positive for GBS, she will receive antibiotic treatment during childbirth to reduce the chances of her passing on the bacteria to her baby. Penicillin is the most common antibiotic used for treating GBS. However, if a pregnant woman is allergic to penicillin, there are other effective antibiotics that can be used. If the mother’s GBS status is unknown during delivery, the decision to give her antibiotics will be based on certain risk factors. Remember though, even with testing and preventative treatment, some babies may still get GBS disease.