What is Penetrating Head Trauma (Stab Wounds in the Head)?

The brain is the main organ of the nervous system, which controls and coordinates many functions in our bodies. The primary sections of the brain are the cerebral cortex, thalamus, hypothalamus, limbic system, midbrain, cerebellum, medulla oblongata, and pons. These regions send out signals through the cranial nerves. The ventricles inside the brain contain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

The brain has a network of arteries at the front and back, called the circle of Willis. Vein- like structures known as venous sinuses carry away waste from the brain. The sinuses collect blood from both the superficial veins, which follow arteries, and the deep veins in the brain.

The brain is housed within the skull or cranium, which is made up of the frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital, sphenoid, and ethmoid bones. These bones have different thicknesses, which means some parts of the skull are more prone to injury than others.

The brain is also protected by the meninges, consisting of three layers called the dura, arachnoid, and pia mater. The dura mater is the outermost layer lying just below the skull. The middle layer, the arachnoid mater, has small outward bulges that allow CSF to return to the blood. The innermost layer is the pia mater, which sticks closely to the brain.

A penetrating head injury (PHT) occurs when a foreign object breaks through the skull, and it directly affects the dura mater and brain. This is the most dangerous type of head injury. A large portion, 70-90%, of individuals with this injury die before they can get to a hospital, and half of the people who make it to the hospital die during immediate treatment. Recovery for survivors can be long-lasting and difficult.

Current guidelines for handling PHT are based on military practices from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars 20 years ago. There’s no universally accepted protocol but, generally, the first steps involve an initial check-up, stabilization, a detailed neurological exam, and appropriate imaging studies. Surgery, often necessary in PHT cases, focuses on reducing pressure in the head, safely removing any debris, and sealing up the dura mater.

What Causes Penetrating Head Trauma (Stab Wounds in the Head)?

Penetrating head trauma (PHT) can be caused by high-speed incidents, such as being hit by bullets or fragments from an explosion. PHT can also occur from slow-speed injuries, like being stabbed with a knife. The severity and direction of the injury determine how the condition appears.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Penetrating Head Trauma (Stab Wounds in the Head)

In the United States, roughly 20,000 injuries from headshots happen each year. The majority of deaths from penetrating head trauma (PHT) are caused by firearm injuries. Based on data from the US military from 2000 to 2015, about 1.47% people experience this condition. Annually, PHT results in around 32,000 to 35,000 civilian deaths.

Signs and Symptoms of Penetrating Head Trauma (Stab Wounds in the Head)

When handling a medical emergency like penetrating head trauma (PHT), clinicians initially focus on evaluating the patient’s airway, breathing, blood circulation, and overall mental and physical state. This quick primary assessment is crucial, especially in situations where the patients are unconscious or aren’t breathing with or without a presence of a pulse. After the patient is stabilized, a more comprehensive ‘secondary survey’ ensues.

As much information about the incident that led to the PHT should be gathered. Since patients with PHT are often disoriented, bystanders, emergency medical service teams, and other rescuers can provide invaluable information. Key details needed include:

- The time and date of the injury

- Details about the weapon used and the injury location

- Contextual events related to the injury

- Any neurological symptoms experienced such as loss of consciousness or seizures

- Details of any pre-existing medical conditions

- Any medication currently being taken by the patient, especially blood thinners

The patient should be closely monitored for indications of increased pressure within the skull, as initial symptoms of PHT like headaches, nausea, vomiting, or swelling of the optic disc can be easily overlooked.

The physical examination should involve a detailed inspection of the superficial wound, identifying any entry or exit wounds, and checking other body parts for additional wounds. The presence of a hematoma (a collection of blood outside of blood vessels) beneath the scalp can be significant, as it can compromise blood flow. It is vital to look for any discharge of cerebrospinal fluid, blood, or brain tissue from the wound and to check all body cavities for leftover foreign objects, fragments from the weapon used, teeth, or bone pieces. Lastly, the patient’s neurological condition should be comprehensively assessed, starting with their level of consciousness and followed by checks of their motor skills, sensitivity to touch, reflexes, and mental state.

The way PHT presents itself can vary depending on factors such as the cause of the trauma, location of the injury, and whether additional injuries are present. Symptoms on one side of the body can help identify the area and extent of the brain injury. It is important to note that the areas of the brain affected might not necessarily be just around the location of impact.

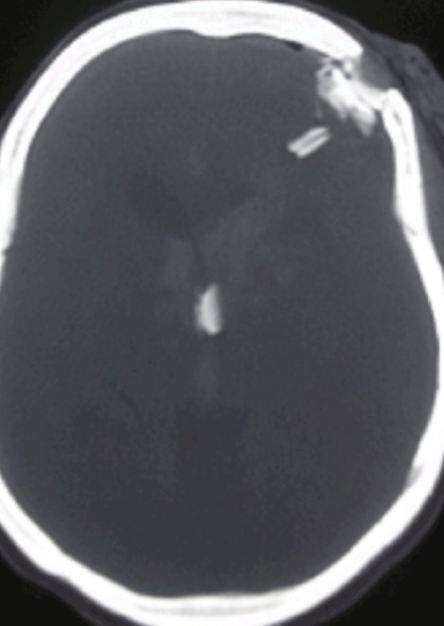

break in the left frontal cranium and dura mater. A fragment of the weapon has

penetrated the brain. Edema in the area collapses the left lateral ventricle.

Testing for Penetrating Head Trauma (Stab Wounds in the Head)

If you’ve experienced a traumatic injury, your doctor will likely first order a few essential blood tests. These could include a full blood count, blood typing, coagulation studies (to check how your blood clots), and a basic metabolic panel to check your overall health status. If the injury is severe that it might require an emergency operation, these blood tests can equip the surgical team with information about any potential health issues that need to be addressed either before or during the surgery.

Medical imaging tests, including regular X-rays, computed tomography (CT scans), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), will also likely be carried out. Let’s break down what these tests mean:

Regular X-rays help the doctors see the shape of any penetrating objects and whether there are any fragments of bone or metal lodged in the brain. They can also detect the presence of air within the skull, a condition known as pneumocephalus. In severe accidents involving multiple injuries (polytrauma), X-rays can be used to document all other injuries.

CT scans, on the other hand, are a type of X-ray that provides more detailed images. They’re often the preferred choice for head injuries. CT scans can show fragments of bone or metal lodged in the brain, which helps doctors understand the path the objects took when they hit the skull and the patterns of brain injury that have resulted. However, CT scans might not show objects that don’t absorb X-rays well, such as fragments of wood.

Lastly, there’s MRI. MRI scans use a magnetic field to produce detailed images of the body. If there’s a chance that a wooden object might have hit the skull, an MRI scan can locate it. Additionally, MRI scans can provide detailed information about injuries to soft tissues. However, if there’s a chance that there may be metal fragments in the brain, MRI should not be performed due to the risk posed by the machine’s strong magnetic field.

Please remember these descriptions are simplified explanations, and the exact diagnostic processes may vary case by case. It lies in the hands of the healthcare professionals to decide the most appropriate testing and treatment based on each patient’s unique circumstance.

Treatment Options for Penetrating Head Trauma (Stab Wounds in the Head)

When a patient is affected by a penetrating head trauma, it is vital not to remove the penetrating object before reaching the appropriate medical facility. Once the patient reaches a trauma center, top priority is given to stabilizing their condition according to Advanced Trauma Life Support guidelines, which includes maintaining blood pressure above 90 mm Hg. Fast action by a trauma team is often key in identifying and treating such severe injuries.

The main goals of managing a head trauma case include:

* Saving the patient’s life by applying quick resuscitation and decompression methods,

* Preventing infection by ensuring that there are no leaks in the dura (a protective layer of the brain),

* Preserving neural function by actively preventing complications such as meningitis, seizures and stroke,

* Restoring physical functionality via cranial surgery (cranioplasty).

An effective approach includes rapid transport of the patient from the injury site to a skilled medical facility.

On arriving at the emergency department, the aim is to stabilize the patient, assess their condition and if necessary, prepare for surgery. In the meantime, any penetrating objects must not be removed from the skull, but must be stabilized and protected from motion to avoid causing any further injury. At the same time, the wounds must be kept sterile.

When surgical intervention is necessary, it aims at stopping the bleeding and preventing infection. The early goal of the surgery chiefly revolves around a strategy of radical debridement, which involves thorough removal of foreign bodies and damaged tissue to limit injury and encourage healing.

Any surgical treatment should ideally be performed within 12 hours after the injury to prevent complications. This includes detailed debridement, removal of hematomas and superficial bone or missile fragments, plus plugging potential air emboli related to venous sinuses. Sealing the dura and maintaining control of the cervical carotid during lateral skull base exploration are just two of the critical steps.

After the surgery, the patient must be carefully monitored in a neurointensive care unit, with a focus on maintaining specific levels of intracranial pressure and cerebral perfusion pressure. Other essential medical management practices involve providing proper nutrition and taking precautions to prevent complications like deep vein thrombosis, seizures and stroke.

What else can Penetrating Head Trauma (Stab Wounds in the Head) be?

When considering a diagnosis of Penetrating Head Trauma (PHT), doctors must rule out several other conditions that could show similar symptoms. These include:

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Stroke

- Cancer spreading to the brain

- Brain aneurysm, a bulging blood vessel in the brain

- Frontal lobe syndrome, a condition affecting personality and behavior

- Epilepsy

- Hydrocephalus, a condition where fluid builds up in the brain

- Diseases caused by prions, misfolded proteins that can cause other proteins to misfold

However, careful examinations and imaging tests can help distinguish PHT from these conditions.

PHT can show up in different ways, because the way items move inside the skull can vary. This includes:

- Penetrating injuries where an object goes through the skull and the tough covering of the brain but stays inside the skull, typically without leaving an exit wound

- Perforating injuries, where something goes completely through the head and leaves both an entry and exit wound

- Tangential injuries, where objects or pieces bounce off the skull but may still push pieces of the skull into the brain

- Ricochets, where an object bounces around inside the skull

- Careening, where the object goes into the skull but moves along the outside of the brain without going into the brain tissue

A thorough evaluation can help determine between these different types of injuries.

What to expect with Penetrating Head Trauma (Stab Wounds in the Head)

The clinical outcomes for penetrating head trauma (PHT) are usually quite poor. Lower scores on the Glasgow Coma Scale (a scoring system used to evaluate consciousness levels), being older, lack of oxygen, low blood pressure, and the use of ballistic weapons worsen the prognosis. Lateral (side) injuries have the worst outcomes.

Injuries that penetrate a critical area in the brain—known as the “zona fatalis,” which includes the third ventricle, hypothalamus, and thalamus—and show a “tram-track” sign on medical images have nearly a 100% death rate.

Self-inflicted PHT causes death in 35% of cases. Also, a review of 1738 patients showed that 34.2% of PHT cases had a poor outcome, and the overall death rate was 18%. A Glasgow Coma Scale score above 8 when the patient first arrives for treatment predicts a lower death rate.

However, military medical strategies–which provide immediate treatment–result in four times more patients living independently two years later compared to civilians with PHT. Monitoring intracranial pressure (the pressure inside the skull) also improves survival rates.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Penetrating Head Trauma (Stab Wounds in the Head)

After surviving Penetrating Head Trauma (PHT), a number of complications can surface. They can be grouped into categories based on the time they occur:

Early complications

- Hypoxia: lack of sufficient oxygen

- Hypotension: low blood pressure

- Hematoma: a solid swelling of clotted blood

- Ischemia: inadequate blood supply to the brain

- Raised ICP: increased pressure inside the skull

- Anatomic defects: physical abnormalities in the brain

- Neurogenic pulmonary edema: fluid in the lungs due to brain injury

- Stunned myocardium syndrome

- Imbalance of electrolytes, potentially from certain diseases

- Neuroendocrine dysfunction: problems with the brain-endocrine system

- Traumatic optic neuropathy: damage to the optic nerve from sudden injuries

- Cranial nerve injuries: damage to the nerves that emerge directly from the brain

Intermediate complications

- Refractory cerebral edema: swelling in the brain not responding to treatment

- Acute hydrocephalus: buildup of fluid in the brain

- Seizures

- Vasospasm: narrowing of blood vessels

- CSF leak: leakage of the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord

- Pseudoaneurysm: false aneurysm in the brain

- Deep venous thrombosis: a blood clot within a deep vein

Late complications

- Infection

- Late hydrocephalus: delayed buildup of fluid in the brain

- CSF fistula: an abnormal connection involving spaces containing CSF

- Venous sinus occlusions: blockages in the veins of the brain

- Arteriovenous fistulas: abnormal connection between an artery and a vein

- Trephination syndrome: complications related to surgical hole in the skull

- Temporalis atrophy: weakening of the temporal muscle at the side of the skull

- Hygroma: a fluid-filled sac

- Scalp necrosis: death of scalp tissue

- Complications relating to cranioplasty: reconstructive surgery of the skull

- Toxicity from retained bullet fragments

Certain types of wounds, such as grossly contaminated wounds or those that cross the middle of the brain, increase the risk of infection. Infections following PHT used to be much more common. Nowadays, infections occur in 4 to 11% of military patients and 1 to 5% of civilian patients. Antibiotics are typically given for 7 to 14 days to prevent infection. Specific types of bacteria are more commonly associated with secondary infections.

Vascular complications, such as those involving the blood vessels in the brain, occur in 5 to 40% of PHT patients. Certain factors increase the risk of these complications. About 30 to 50% of PHT patients develop post-traumatic epilepsy, most often within the first two years following the injury.

The two most common complications of a particular type of PHT (“non-missile” PHT) are vascular damage and infection. Certain factors increase the likelihood of these complications. Recent studies revealed various rates of complications, including infection, seizures, and leaks of cerebrospinal fluid. Severity of symptoms and imaging findings were linked with a higher risk of neurological impairment and mortality.

Preventing Penetrating Head Trauma (Stab Wounds in the Head)

The best ways to prevent Penetrating Head Trauma (PHT) include:

* Wearing safety helmets

* Being careful with firearms

* Following safety rules at work

* Avoiding falls

* Practicing safe driving

* Staying away from violence

* Improving the safety of buildings and roads

* Checking for fall risks

* Regular health check-ups for people with a high chance of falling or getting into accidents

While these steps cannot prevent all cases of PHT, they can greatly reduce the chances of it happening. The prevention of PHT involves a comprehensive strategy that includes learning about safety, adopting public safety rules, using engineering techniques to create safer environments, and promoting safety in different areas of life.