What is Metacarpal Fracture?

The metacarpals are the bones in your hand that form the base for your fingers’ working system. When these bones get fractured, they can cause significant disability, especially for those who need their hands for their work or active lifestyle. The cause of these fractures varies widely.

Metacarpal fractures occur frequently among the general population but are particularly common for people involved in contact sports such as boxing or football, as well as those whose jobs involve manual labor. Given the intricate structure and function of the hand, it’s important for orthopedic surgeons and other healthcare providers to be able to quickly identify and treat these injuries to prevent further complications.

What Causes Metacarpal Fracture?

Metacarpal fractures, or breaks in the bones of the hand, are usually caused by direct injury. This can often happen because metacarpal bones are close to the skin’s surface and can break if the hand is used to block a force, like in a fall. When the top of the hand is hit directly, it can cause the middle part of the hand bone to break across, sometimes into several pieces, depending on how hard the hit was. When the hand twists or gets an axial load (force along the length of the hand), it could result in an oblique fracture, which runs diagonally across the bone. If the hand is bent with an axial load, a triangular piece, or a ‘butterfly fragment’, can break off the bone. The severity of these fractures can vary depending on the amount of force from the injury.

One of the most famous types of metacarpal breaks is known as a “boxer’s fracture”, indicating a break at the neck of the fifth hand bone with a forward displacement. This type of fracture makes up 20% of all hand fractures. These fractures typically happen due to a force down the length of the bone combined with slight bending movement, causing the neck of the bone to break and move forward. Similarly, fractures within the joint at the base of the hand also result from forces along the length of the bone and could eventually lead to arthritis in the joint connecting the hand and wrist.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Metacarpal Fracture

In simpler terms, fractures of the metacarpal bones in the hand are the third most common type of upper body fractures, following breaks in the radius and the fingers. These metacarpal fractures make up about 40% of all hand injuries.

People aged between 18 and 34 are especially prone to these fractures, with it being the most common hand injury in this age group. Among all people with metacarpal fractures, 76% are male.

The risk of a metacarpal fracture increases as you go from the thumb side (radial side) to the little finger side (ulnar side) of the hand. Thus, fractures in the 5th metacarpal bone, closer to the little finger, are more common than fractures in the 2nd metacarpal bone, closer to the thumb.

It’s important to remember, though, that metacarpal fractures can happen by themselves or along with fractures of other metacarpal bones or other bones in the body.

Signs and Symptoms of Metacarpal Fracture

If you suspect that you have a broken knuckle bone, or metacarpal fracture, there are several signs you can look for. Common symptoms include swelling, bruising, tenderness when touched, and pain when moving your hand or fingers. More specific signs of this kind of fracture include a loss of knuckle height, twisted fingers, or fingers that cross over each other, known as “scissoring”. These symptoms, along with information about the incident, can help your doctor decide whether or not to investigate further for a broken bone.

Looking for twisted fingers (also known as a rotational deformity) is an important part of examining a suspected metacarpal fracture. To see if this is present, your doctor will observe if your fingers are overlapping each other when you present with the injury. They will also ask you questions about things like whether the hand injured is your dominant one, your current working status, if you take part in athletic activities, and if you’ve ever fractured a bone before.

- Swelling

- Bruising

- Tenderness

- Pain during movement

- Loss of knuckle height

- Twisted fingers

- Fingers crossing over each other (‘scissoring’)

It’s also important to check the skin’s condition. This is especially crucial to rule out certain types of injuries, like “fight bite” injuries, where a person punches someone else in the mouth, resulting in a mix of a laceration and puncture wound from teeth. Also, if you have a wound on the top part of your knuckle joint, this could mean your joint has been exposed or that you have an open fracture, until further examination suggests otherwise. Injuries to the top of the hand also often go hand in hand with cuts to the tendon that straightens your fingers, which is something else that needs to be checked for during the evaluation.

Testing for Metacarpal Fracture

When determining whether you have a metacarpal fracture, which is a break in one of the long hand bones, doctors will typically use an X-ray. The X-ray is taken from multiple angles, including straight-on (PA), side (lateral), and diagonal (oblique). Diagonal X-rays in specific rotations help doctors see fractures in different areas of the hand.

Fractures are categorized according to their characteristics, such as whether they are straight (transverse), diagonal (oblique), spiral, displaced, or fragmented (comminuted). The location of the fracture, like whether it’s on the tip, the head or neck, the shaft, or the base of the bone is also significant. Doctors consider other factors, like the presence of multiple fractures, any twisting or shortening of the bone, and how much the bone has moved from its normal position. These things can show if the fracture is unstable and needs to be fixed through surgery.

Sometimes, a CT scan may be needed, especially for fractures at the base of the metacarpal. This helps doctors see if the break extends into the joint and whether surgery is needed.

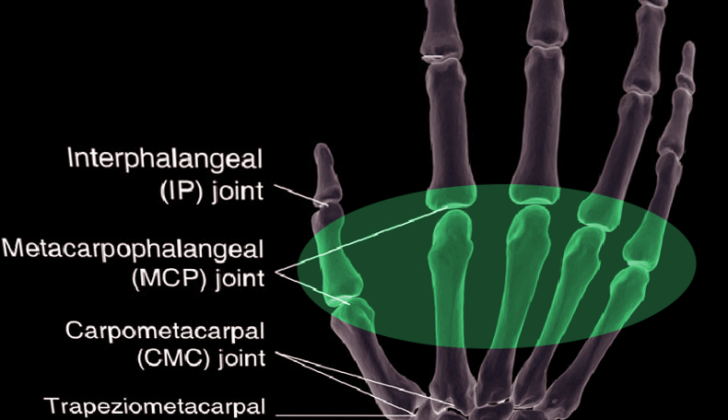

Another key point in diagnosing and treating is understanding the height loss of the metacarpal. If the bone loses height, it can lead to an extension lag in the affected finger. Basically, your finger won’t extend as much as it usually does. On average, with every 2 mm of bone height loss, the finger experiences a 7-degree lag in its extension at the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint, where your finger meets your hand.

However, due to the natural hyperextension at the MCP, you can lose up to 5 to 6mm of bone height (equivalent to 21 to 30 degrees of extension lag) before it starts significantly affecting the function of your hand.

In addition to considering these factors, doctors look into the natural structure and movement range of your fingers. Notably, your index and middle fingers have limited motion compared to your ring and small fingers due to their anchoring points, so they can only withstand a certain level of change in their normal position. However, the ring and small fingers can bear greater deviations due to their wider range of motion.

Treatment Options for Metacarpal Fracture

When treating hand fractures, doctors have a variety of options. While some fractures can be treated without surgery if they have a suitable pattern or alignment, others may require surgery. Common options include wiring, internal fixation, or open surgery with screws or plates. The goal is to start moving the hand again 2 to 4 weeks after surgery to prevent stiffness and return to everyday activities as quickly as possible.

Whether or not to opt for non-surgical treatment depends on the stability of the hand bone. This includes checking for any loss of height, unusual finger positioning, multiple fractures, and tilt of the fracture. If the fracture is within acceptable limits, non-surgical treatment is an option. But if the fracture is outside of these limits, realignment is necessary, even if non-surgical treatment is preferred.

Generally, all hand fractures should be treated with appropriate anesthesia, with the bone parts being gently pulled apart and pressure applied to the hand, primarily for fractures of the bone shaft. For fractured neck joints, bending the knuckle joints to 90 degrees helps to control the broken fragment. Special attention should be given to small finger fractures, as these often require fixation. Once realignment is complete, the hand is immobilized in the “intrinsic plus” position, where the knuckle joints are bent to 90 degrees with full extension of other joints to prevent any contractures while immobilized. This is maintained for 2 to 3 weeks with interval evaluations for loss of realignment.

If the hand remains well positioned, patients may gradually start moving the involved digit. However, the fractures can displace even after perfect realignment and might require fixation.

If fractures have failed non-surgical treatment, are open, or are outside the accepted criteria, the preferred treatment would be either closed or open surgery with internal fixation. Proper rotation and alignment must be achieved to restore hand motion and grip strength. For open fractures, initial treatment should include administering antibiotics, tetanus prevention, and early cleaning of the wound.

Fractures of the hand bone head are rare but most happen due to direct trauma and require surgical fixation when there is a significant defect in the joint surface or instability.} Fractures with large joint pieces are usually fixed with small screws, while plates are used for injuries extending to the bone shaft. For those fractures that are extremely fragmented, wire fixation is appropriate. However, care must be taken to avoid damaging the joint. The hand must be immobilised for two weeks afterwards.

For hand bone neck fractures, wires within the bone are the main treatment to help control tilt and restore height. These fixing options, however, don’t control rotation. Careful examination of rotation should be performed to ensure proper alignment. A downside to wire placement within the bone is the need for a secondary procedure to remove the hardware. Other options include screws within the bone, which still present the issue of rotational control after surgery but don’t necessitate a second procedure for hardware removal.

Fractures of the hand bone shaft are the most common, and those with diagonal and spiral fracture types have a higher likelihood of rotational misalignment, requiring surgical fixation. Options for fixation of these injuries include wires within the bone, plate and screws, and most recently, headless screws within the bone. While wires provide a minimally invasive approach, they are less stable compared to plates and screws, which can be used in multiple modes for different fracture types, providing more rigid fixation.

Extra and intra-articular injuries can occur at the base of the hand bone. Extra-articular fractures mostly occur separately from other injuries, while intra-articular fractures can occur with joint dislocation, especially in the ring and small fingers. For extra-articular base fractures, many of them occur in the joint and bone-shaft junction and can be properly fixed by wires to avoid cutting off blood supply to fracture parts, but sometimes require an open approach with plate and screw fixation for direct visualization in complex fracture types.

Thumb bone fractures deserve special attention, given the relative lack of muscle and deep ligament support. Despite the thumb tolerating more tilt than other hand bones due to its higher mobility, a tilt of over 30 degrees often fares poorly with non-operative management.

Open fractures should be treated with local wound care and antibiotics. The role of timely cleaning with removal of any dirt/debris and primary versus secondary wound closure in the acute setting is controversial, clinicians should consult the hand surgical service on call at the institution.

After surgery, patients require immobilization in the ‘intrinsic plus’ position to reduce joint capsule contraction. It’s also important for patients to elevate their affected extremity as often as possible, as swelling can significantly increase pain and limit range of motion, thus creating a stiff hand. For those with plate and screw fixation, immobilization should stop at the first post-surgery visit, and gentle range of motion exercises should commence.

What else can Metacarpal Fracture be?

When diagnosing hand injuries, doctors look at both bone and soft tissue damage. This can include injuries to muscles, tendons, and ligaments. While noticeable changes to the shape of the hand can suggest a fracture, the most reliable method to confirm a broken bone is through medical imaging such as X-rays.

What to expect with Metacarpal Fracture

The outcome of a metacarpal (hand bone) fracture depends on various aspects like the exact type of break, how it’s fixed, and any issues that may come up during recovery. Generally, with proper treatment, people with these fractures have a good prognosis. However, the doctor also has to consider the patient’s expectations when treating these fractures.

There are many ways to fix metacarpal fractures, which depend on where the fracture happened. Despite this, surgical treatment often leads to positive results.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Metacarpal Fracture

Similar to most fractures, complications from metacarpal fractures can include failure of the fractured bone to heal properly, improper alignment when the bone heals, stiffness of the hand, and infections. After surgery, infections need to be treated with antibiotics. Additionally, any non-living tissue and surgical hardware might need to be removed. If an infection is present at the time of planned surgery for fixing the bone or reconstructing it, the surgery might have to be postponed till the infection has been treated.

When the hand fracture occurs in the dominant hand, stiffness can be particularly problematic. For patients who are treated with a splint or a pin inserted through the skin, exercises should be started four weeks after treatment or as soon as the bone has healed. In patients who received fixation with a plate, exercises can be started immediately after the removal of the stitches, which usually happens at the first post-surgery visit.

It is quite rare for metacarpal fractures not to heal at all, occurring in fewer than 1% of patients. If a patient is not undergoing surgery, the bone usually heals within three to six weeks from injury, and in the case of patients who undergo surgery, this timeline starts from the time of surgery. If the fractured bone has still not healed after a considerable time, and there is still pain, it might be due to bone loss, improper immobilization or an infection. If similar conditions persist for nine months, it is diagnosed as a permanent failure to heal. Most commonly, this happens in patients who were treated with fixation using K-wires. In such cases, a part of bone extracted from another site is used to promote healing, and the bone is rigidly fixed using plates and screws to prevent any movement at the fracture site.

Misalignment of the bone when it heals can be detected by physical examination and X-ray scans focusing on the height of the knuckle or any abnormal rotation or overlap of the fingers. This can result in arthritis due to injury to the joint. For deformities resulting in rotation or changes in length, surgery to correct the bone shape can help in restoring the proper alignment of the fingers. For cases where the joint has healed in a dislocated position, joint replacement or fusion of the joint are two options to achieve acceptable results.

As in any surgery, there is a chance of injuring the soft tissues, nerves, or arteries. It is very important to prevent injury to these structures. This is especially true when operating on the metacarpals since a lot of nerves transmit sensation from this area. In the case of surgeries done from the back of the hand, particular care needs to be taken to avoid damaging the nerves.

In case a plate is used to fix the fractured bone, it can cause irritation to the tendon, which can worsen up to the point of rupture. Therefore, it is recommended to close the membrane around the bone whenever possible to prevent this risk. Healthcare providers should monitor the tendons that straighten the fingers after both surgical and non-surgical treatment of these injuries.

Recovery from Metacarpal Fracture

There are various methods to fix a fractured metacarpal bone (one of the five bones in the hand), and surgery often results in successful recoveries. For those treated using a non-surgical technique involving K-wire, the hand usually ends up with more flexibility than if plate fixation is used. But aside from this increased movement, other healing indicators like the Disability of Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) scores, grip strength, and pain level are generally the same.

Though this information is mainly based on results from fractures in the fifth metacarpal bone, it’s logical to think that similar results could be expected for the four other metacarpal bones. However, when using these non-surgical procedures to secure the bone, surgeons need to be careful about potential twisting at the fracture site, as this could lead to improper healing of the bone.

Rehabilitation aims to restore complete hand and finger movement. Simple exercises using light resistance tools like rubber bands or squeeze balls are essential, especially if any scarring occurs or the extensor muscles (the ones used to straighten the fingers) become sluggish.

Preventing Metacarpal Fracture

Since the main causes of these types of injuries usually involve sports and work activities, it’s crucial that athletes and working individuals learn about safety measures related to their particular sport or job. Athletes, in particular, should be informed about the potential serious consequences of these injuries, as well as how to prevent them. If these injuries aren’t properly treated or managed, they could result in significant health problems.