What is Radicular Back Pain?

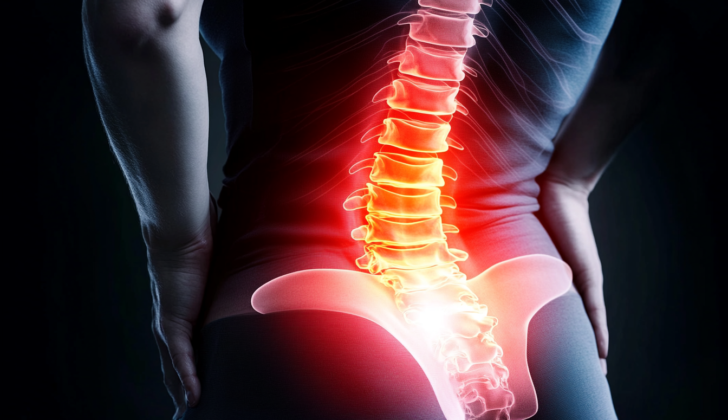

Acute lumbosacral radiculopathy is a common condition that affects more than one nerve root in the lower back region. It can cause pain, numbness, and difficulty with movement based on how much pressure is on the nerves. Some people’s symptoms are less severe and get better on their own. The most common symptom is an odd feeling called paresthesia. Some people also experience back pain that stretches into the foot, which can be confirmed by a positive result from a leg-raising test. In many cases, muscle strength is maintained because muscles obtain signals from several nerve roots. Therefore, muscle strength is typically affected only in severe cases of radiculopathy.

The main reasons for lumbar radiculopathy are a slipped disc that puts pressure on the nerve root or spine arthritis (spondylosis). It can be sudden or progress slowly over time. Imaging such as MRIs isn’t always helpful because almost 27% of people without back pain have been found to have disc herniation on an MRI. Moreover, this random finding does not predict future back pain.

To figure out if a herniated disc is causing a patient’s pain, a complete history and physical examination is required, and the symptoms should match the imaging results. Patients with lumbar radicular pain often feel better with simple management strategies. If these strategies don’t work, an MRI may be needed for further evaluation and to determine how severely the nerve root is involved. Furthermore, if the symptoms are severe, consideration should be given to a specialist referral for treatment such as an epidural steroid injection or surgery to relieve pressure.

What Causes Radicular Back Pain?

Lumbar radiculopathy, a condition that affects the nerves in your lower back, is often caused by nerve root compression. This can be a result of a disc slipping out of place, known as disc herniation, or due to a condition called spondylosis, which is essentially wear and tear of the spine.

Disc herniation can occur due to a sudden injury or over time due to long-term wear and tear on the spine. When a disc herniates, it can cause pain in the surrounding tissues, including ligaments, blood vessels, and the outer layer of the spinal cord.

Spondylosis, on the other hand, shrinks the space in your spine, whether that’s in your spinal canal, neural foramen (the gaps through which your nerves pass), or the lateral recess (the side parts of the canal). This shrinking of spaces often happens due to age-related arthritis in the lumbar spine, but it can also be due to inflammation, infection, injury, blood vessel disease, or a tumor. When a nerve root in your spine gets compressed, it can lead to lack of blood flow, inflammation, or swelling and cause damage.

The wear and tear of the disc between your vertebrae, the joints between your vertebrae and the paired joints at the back of your spine can injure the nerve roots in your spine. Bone spurs or a herniated disc can squeeze the spinal cord or the nerves, which causes pain.

If the wear and tear of the spine is severe, it can cause misalignment, a condition termed as spondylolisthesis. The most common sites of injury are between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae (L4-L5) and between the fifth lumbar and first sacral vertebrae (L5-S1). These sections are responsible for most of the lumbar spine’s movement – so they’re more susceptible to injury. Approximately 90% of lower back and upper leg pain from compressed nerves occurs at these levels.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Radicular Back Pain

Lumbosacral radiculopathy, which affects the nerves in the lower back, is a common condition. On average, between 3 to 5% of adults will experience symptoms at some point in their lives. The most common type is L5 radiculopathy.

- Between 63 and 72% of patients experience a sensation of tingling or prickling, known as paresthesia.

- About 35% experience pain that spreads to the lower limb.

- Approximately 27% of patients report feeling numb.

- Up to 37% of patients have muscle weakness.

- Up to 40% have no ankle reflexes, and 18% have no knee reflexes.

Interestingly, less than 5% of patients with sudden lower back pain have it because of disc herniation. If a patient walks with a broad-based gait and tests positive on a Romberg test, there’s a 90% chance they might have a lower spine syndrome. The EMG test, used to diagnose radiculopathy, has a sensitivity ranging from 50 to 85%.

Signs and Symptoms of Radicular Back Pain

Radiculopathy, a condition resulting from a pinched nerve in the spine, usually impacts specific lumbar (lower back) areas labeled as L2, L3, L4, L5, and S1. The different types of radiculopathies often share symptoms, but there are some distinct signs for each that can help in diagnosing them.

L2, L3, and L4 radiculopathies often cause back pain that radiates to the front of the thigh, potentially reaching the knee and even the foot. During a physical check-up, patients might show weakness when extending the knee, hip adduction (bringing the leg inward), and flexion (bending the limb at the joint). Besides, they could present a loss of sensation in the painful area on the front of the thigh and a reduced knee-jerk reflex. Coughing, straightening the leg, or sneezing can worsen these symptoms.

In L5 radiculopathy, patients might feel acute back pain that spreads down the side of the leg and into the foot. During an examination, doctors may observe muscle weakness when extending the big toe, turning the foot inward and outward, extending the toes, and bending the foot upwards. Chronic cases might cause muscle atrophy (wasting) in the front of the leg. In severe cases, leg abduction (moving the leg outward from the midline of the body) can also be weakened.

S1 radiculopathy typically causes pain from the sacrum (base of the spine) or buttocks that radiates down the back of the leg, potentially reaching the foot or perineum (the area between the anus and the genitals). Upon examination, patients might have weakened plantar flexion (bending the foot to point the toes away from the body) and a loss of sensation along the back of the leg and the outside of the foot. The ankle-jerk reflex can also be lost or reduced.

Doctors also look for other indicators in a physical exam, such as difficulty standing from a seated position, a history of knee buckling, or a toe drag when walking. If the deep tendon reflexes are diminished for L4 and L5, it also supports a diagnosis of lumbar radiculopathy. Furthermore, a couple of straight leg raising tests, known as a Lasegue test and a Bowstring sign, as well as an internal hamstring reflex for L5 radiculopathy, can provide useful diagnostic information.

Testing for Radicular Back Pain

If you are experiencing severe back or leg pain that’s getting progressively worse, or if your doctor suspects you may have a severe underlying condition like an abscess, tumor, or cauda equina syndrome (a rare disorder affecting the bundle of nerve roots at the lower end of the spinal cord), they will likely suggest urgent brain and spine imaging. This is important even though sometimes imaging can highlight abnormalities in people who aren’t experiencing any symptoms.

The most useful tool to identify any serious underlying issues and evaluate the need for surgical intervention is the Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan of the lumbosacral spine – the lower section of your spine. This type of scan can help tell the difference between inflammatory, malignant (cancerous), or vascular (blood vessel) disorders much better than CT scans.

When the doctor suspects you might be suffering from a condition called lumbar radiculopathy – a disorder resulting from a damaged nerve root in the lower back, they would usually recommend an MRI with contrast, unless you have a medical condition that contraindicates it. Your doctor could suggest nerve conduction studies – a type of test that measures how well and how fast the nerves can send electrical signals, if the results of the imaging are unclear or do not show anything, but they still have a strong suspicion of radiculopathy.

Computed Tomography (CT) scans aren’t as good as MRI when it comes to visualizing the nerve roots, so they may not be the first choice for diagnosing radiculopathy. However, they can provide a better assessment of the bony structures within the body. X-rays of your lower back could also be done, but they may not be very helpful in understanding your radiculopathy.

If you cannot get an MRI for some reason (like having a pacemaker or defibrillator), or if the results from the standard CT or MRI are not clear, your doctor may recommend a CT myelogram. It involves using a special contrast dye and taking pictures of your spine. This test is particularly recommended if you have had spinal surgery before and have hardware in your spine.

If your symptoms persist for more than 3 weeks, more advanced tests like an Electromyography (EMG) or nerve conduction study may be conducted as they rely on specific changes in the nerve and muscle functions that take some time to develop after an injury. These tests are helpful in pinpointing the specific damaged nerve roots, distinguishing between new and old nerve damage, and confirming the presence of certain types of nerve damage. These tests can provide useful information if imaging tests have not been able to determine the cause of your symptoms.

Sometimes, your doctor may also recommend testing your cerebrospinal fluid – the fluid around your brain and spine. This is particularly done if you’re experiencing worsening symptoms, the results of your imaging tests are not clear, or there’s no improvement in your condition. However, other tests such as somatosensory evoked potentials and discography (injecting dye into the disc’s nucleus and then using X-ray to view it) are usually not recommended as they haven’t proven to be helpful in diagnosing lumbar radiculopathy.

Treatment Options for Radicular Back Pain

Radicular symptoms, often associated with nerve root irritation or compression, fall into three categories. Mild radiculopathy presents as subtle sensory loss and pain without any muscle weakness. Moderate radiculopathy is characterized by sensory loss or pain with some muscle weakness. Severe radiculopathy shows significant sensory loss and pain paired with notable muscle weakness. The severity level affects how a person’s symptoms are treated.

A good number of cases of lumbosacral radiculopathy, which is a type of radiculopathy affecting the lower back and legs, resolve by themselves over time. Most are mild cases that get better within six weeks from when symptoms first appear. Patients are often advised to lose weight if needed, as many people with low back radicular pain have higher body weights. There is a solid chance of getting better even without treatment if the radiculopathy is due to a slipped disc or spinal stenosis.

For the primary care of lumbar radiculopathy, doctors typically recommend conservative approaches that includes medication like acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs), and changes in activities. Strong painkillers, such as opioids, are reserved for patients with severe pain who haven’t found relief from other medication. Though acetaminophen is better than no treatment at all, it’s less effective than morphine in reducing pain. Muscle relaxants and benzodiazepines, which are sedatives, aren’t effective for nerve root compression related conditions.

Research shows that resting in bed doesn’t offer any major advantages over just waiting for symptoms to improve on their own. Likewise, getting physical therapy doesn’t necessarily speed up recovery. Professionals generally suggest waiting until symptoms have lasted for more than three weeks before starting physical therapy. Even though some experts have suggested systemic glucocorticoids, which are anti-inflammatory medicines, to help with the pain in acute radiculopathy, studies haven’t found any significant benefits.

For patients with acute lower back and leg radiculopathy, epidural steroid injections can offer modest yet significant benefits for up to three months. After six weeks of conservative treatment, if a patient’s condition hasn’t improved, they might be considered for an injection. However, this treatment tends to be less effective over a longer duration. When compared to conservative treatment, those who undergo surgery, like disc removal, generally have better outcomes in the short term (about 12 weeks). However, after a year or two, surgical and nonsurgical patients usually have similar outcomes. It’s common advice for most patients not to consider surgical options until symptoms have persisted for at least six weeks.

There are differing opinions on the effectiveness of injecting etanercept, which is a medication, directly into the space outside the protective membrane of the spinal cord (epidurally). Some research suggests that it offered significant pain relief at a six-month follow-up when compared to a placebo. Other studies have found its benefits to be similar to those of an epidural glucocorticoid injection, which is another type of medicine.

What else can Radicular Back Pain be?

When diagnosing lumbosacral radiculopathy, a condition that causes nerve pain in the lower back and legs, doctors have to consider a range of potential causes including:

- Herniated disc

- Lumbosacral plexopathy, a large network of nerves in the lower back

- Lumbar spinal stenosis, a narrowing of the spinal canal in the lower back

- Mononeuropathies, conditions affecting a single nerve

- Diabetic amyotrophy, a nerve complication of diabetes

- Cauda equina syndrome, a severe spinal condition

- Non-radicular back pain, pain that doesn’t affect the nerves

Certain situations can give clues to the specific cause. For example, a diabetic patient might be prone to diabetic amyotrophy, presenting with symptoms such as weakness, irregular sensations, and leg pain. New back pain in a patient with osteoporosis could suggest a vertebral fracture. Fever with back pain might indicate an infection in the spine, while pain that disrupts sleep or is not relieved by shifting positions, combined with symptoms such as weight loss or fatigue, could point to cancer.

Spinal stenosis is a condition related to aging and involves symptoms of pain, weakness, and sensory loss in the lower body. It often worsen by standing or walking for long periods. If there are also symptoms like urinary incontinence, progressive weakness, numbness in the inner thighs and buttocks, changes in walking, and problems with bowel control, it may suggest cauda equina syndrome. This serious condition requires immediate surgery, ideally within 12 hours, to avoid lasting damage from nerve compression. In some cases, it can also cause sexual dysfunction.

What to expect with Radicular Back Pain

Lumbosacral radiculopathy, a condition affecting nerves in the lower back and hip area, often resolves on its own. When someone experiences symptoms caused by this condition, it’s essential to reassure them that in most cases, they are not severe and will go away in around six weeks. In fact, it is very common for the condition to improve spontaneously after a disc herniation or lumbar spinal stenosis (a narrowing of the spaces in your lower spine).

It’s equally crucial to talk about the importance of weight loss, as many patients with this condition have a higher than average body mass index (a measure that looks at weight in relation to height). Losing weight can help alleviate symptoms and improve recovery.

However, if a patient’s symptoms become severe or worsen over time, there could be cause for concern. In such cases, further tests like imaging scans may be needed, or in very serious situations, emergency surgery might be required.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Radicular Back Pain

Radicular back pain can bring several complications, including:

- Lumbar radiculopathy: Typically, it has a self-limiting nature, but it can be awfully painful. In extreme cases, this can result in loss of function and a reduced quality of life.

- Emergency complications: Cauda equina syndrome and severe lumbar radiculopathy are considered emergency complications. These situations typically need immediate surgery to relieve pressure.

- Chronic pain: If there is no improvement in the pain within 6 to 12 weeks from when it started, it may turn into chronic pain.

- Muscle atrophy and deconditioning: If radicular symptoms persist and progress slowly, it can eventually cause the muscles to waste away, as the nerves that sustain the muscles in the lower extremities are affected. This progressive loss of muscle function and fitness occurs over time.

Preventing Radicular Back Pain

Lumbar radiculopathy is a usually temporary condition affecting the nerve roots in your lower spine. It may cause severe, burning, or piercing pain that spreads down the leg, less feeling in the legs, or experiencing numbness and a tingling sensation. In some serious situations, it may even cause muscle weakness. If you experience these pain symptoms, it’s important to visit your doctor for an examination. In most instances, the symptoms disappear within 6 weeks if one maintains moderate activity and manages the pain with over-the-counter medications.

If your symptoms persist beyond 6 weeks, a treatment using an epidural corticosteroid injection—which is a shot in your spine— may be of help. However, if the pain continues to intensify and you start feeling numbness and tingling sensation in the region between your legs, or if you have problems with controlling your bowels and bladder, face difficulty in walking, or encounter sexual dysfunction, then this indicates the need for immediate emergency examination and possibly a talk with a surgeon.