What is Neuroma?

Neuromas are harmless lumpy tumors that originate from a nerve. They consist of connective tissue, Schwann cells (cells that produce the protective covering of nerve fibers), and regenerated nerve fibers, and can occur anywhere in the body. Typically, when people speak of neuromas, they’re referring to traumatic neuromas, which are created as nerves heal unregulated after an injury, forming a clump of disorganised nerve fibers and non-nerve tissue growth. Any nerve injury can cause these, be it from surgery, blunt force, nerve severance, or chronic inflammation. Traumatic neuromas can further be categorized based on whether the nerve segments are connected (neuroma-in-continuity), separated (end-neuroma), or trapped within scar tissue. Neuromas can also result from certain diseases (like neurofibromatosis) or actual tumor growths (like an acoustic neuroma or Morton neuroma).

When diagnosing traumatic neuromas, doctors typically begin with a clinical evaluation and then use imaging studies to check the nerve injury’s location and severity. Patients usually report an injury history followed by gradually growing a solid, oval palpable lump, usually smaller than 2 cm, with accompanying pain. The pain from neuromas is often described as stiffness, hypersensitivity, burning, tingling, or sharpness sensation. Neuroma treatments can be surgical or non-surgical and may involve physiotherapy, medication, and high-frequency electrical stimulation. Preventive measures include promptly exploring and repairing nerve injuries after the initial injury to prevent the formation of neuromas.

What Causes Neuroma?

Neuromas, or nerve tumors, come in three types: true neoplasms, traumatic neuromas, and neuromas resulting from genetic syndromes.

Traumatic Neuromas

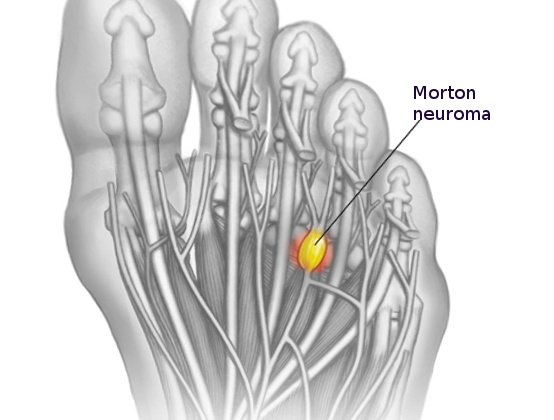

Traumatic neuromas form in response to injury, whether it’s a blunt force, a cut, or a pull. They often appear as Morton neuromas, found in-between the third toe’s metatarsal bones, or Pacinian neuromas, made of skin touch receptors (aka Pacinian corpuscles). Another common cause of traumatic neuromas is surgery. They often develop after hand operations, particularly affecting the superficial radial nerve and the saphenous nerve. Notably, neuromas can also grow post-amputation and are termed stump neuromas. However, the discomfort they cause should not be mistaken with the sensation of a phantom limb.

True Neoplasms

True neuromas are benign (non-cancerous) nerve-sheath tumors that one inherits. They come in various forms:

– Neural fibrolipomas, or sausage-shaped expansions of a nerve’s fatty and fibrous tissue.

– Acoustic neuromas or vestibular schwannomas, which are brain tumors often accompanied by tinnitus (ringing in the ears), hearing loss, and issues with balance.

– Ganglioneuromas, tumors of the body’s automatic nerves predominantly found in the abdomen that might produce hormones.

– Neurothekeomas and nerve-sheath myxomas, both types of perineural tumors.

Genetic Syndrome Neuromas

These neuromas develop due to inherited genetic conditions such as neurofibromatosis or multiple endocrine neoplasia 2B.

Neurofibromatosis involves the formation of numerous neuromas in different regions of the central and peripheral nervous system, leading to skin lesions, hearing and balance problems, or pain. Unfortunately, there is presently no known cure, although surgery can help manage symptoms.

Multiple endocrine neoplasia 2B is a genetic condition defined by the simultaneous occurrence of a type of thyroid cancer (medullary thyroid carcinoma), a type of adrenal gland tumor (pheochromocytoma), and mucosal neuromas.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Neuroma

Even though the reported rates of traumatic neuromas – a type of nerve injury – differ in various studies, it’s important for doctors to know that many of these injuries don’t cause symptoms and often go unnoticed. According to one research, around 1% of people had this kind of injury after a nerve repair, while a different study reported that after losing a finger, about 7.8% had a traumatic neuroma. A separate study on finger amputation reported a 6.6% incidence of the same injury.

Signs and Symptoms of Neuroma

Traumatic neuromas can be diagnosed by assessing symptoms and using various imaging technologies to pinpoint the location and extent of nerve damage. This procedure helps to decide the best course of treatment. Therefore, it’s crucial to gather a full patient history and conduct a thorough physical exam.

Patients with a traumatic neuroma often have a prior injury and later develop a hard, oval lump under the skin that is usually less than 2 cm in size. This lump is often associated with pain. It’s also important to check how and where the injury was treated and if there were any attempts to heal the nerve. If a patient doesn’t remember any injury, the doctor might consider genetic issues or real tumors as the cause. During a physical examination, doctors might identify a clearly outlined, firm lump which may stick to nearby body parts. Touching the lump can cause patients to feel something similar to an electric shock. The pain from neuromas is often described as stiffness, hypersensitivity, burning, tingling, or sharpness.

Testing for Neuroma

If you’re suspected of having a nerve injury known as a traumatic neuroma, doctors usually perform various tests to find out exactly where the neuroma is located and how severe the injury is. After checking your symptoms, they may perform an electromyography (EMG) test, which is used to see how well your nerves are working.

Following the EMG, they might carry out an ultrasound scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to get a more detailed look at the nerves in question. These two scans help the doctors to examine the nerves in your body and determine exactly where and how they’ve been damaged.

Ultrasounds can be re-used multiple times to monitor the nerves, checking if they’re still connected and seeing how they’re doing after you’ve had treatment. MRI scans provide even more detail, showing the doctors a clearer picture of your peripheral nerves (the ones not in your brain or spinal cord).

While some experts prefer using MRI scans because the images they create are so detailed, others suggest using both scans: starting with the ultrasound and then doing an MRI if the ultrasound results aren’t clear or don’t match up with what the EMG test and your symptoms suggest.

Normal blood and urine tests don’t usually help much with diagnosing this condition. However, if a surgical procedure is done to remove a lesion (a damaged piece of tissue), examining it under a microscope afterwards can help rule out cancer.

Treatment Options for Neuroma

Traumatic neuromas are painful growths that can form after a nerve has been injured or cut, and can really affect the quality of your life. The best way to tackle this issue is to prevent it from happening in the first place. Immediately after a nerve has been injured or cut, such as during a surgery, it’s important to reconnect the two ends of the nerve as soon as possible. If a nerve is suspected to be damaged, it’s best to get it checked out at a specialist center that can diagnose and repair the nerve damage. There are many different surgical methods that are similarly effective in preventing the formation of neuromas after an injury.

Generally, the goal of the surgeon is to reconnect the same parts of the nerve under a microscope so that the repair is not under any stress or tension. If there’s a gap in the damaged nerve, sometimes doctors borrow a less important sensory nerve to fill that gap, in what’s called a nerve graft. Sometimes two nerve segments can’t be rejoined, and in cases like these, the nerve is often buried or sewn onto a muscle to help prevent the formation of a neuroma. This technique is called “targeted muscle reinnervation”.

Also, some types of nerve surgeries have been found to pose higher risks of developing neuromas. Some methods like electrocoagulation or cryoneurolysis are preferred because they’re less likely to form neuromas. Interestingly, the direction in which the nerve is cut can also affect neuroma formation – cutting nerves at an angle seems to produce fewer neuromas than cutting straight across.

If a neuroma has already formed, there are some treatments that might help alleviate symptoms. These include using ice packs, elevating the affected limb, resting, using a local anesthetic cream or injection, and taking anti-inflammatory drugs. Some people may also find relief with steroid injections into the lesion. But unfortunately, many people don’t respond well to these types of treatments and still experience pain.

If these more conservative treatments aren’t doing the job, surgery is another option. One common surgery is a “dorsal approach neurectomy,” where the affected nerve is cut out. This surgery has a high success rate, but unfortunately, the neuroma can return in some people. Because of this, surgeons are always looking for ways to prevent this from happening, such as reinnervating target muscles, burying the nerve into the bone or muscle, or using a nerve cap. Recent innovations in this area include using a porcine (pig) extracellular matrix cap after removing the neuroma. If both the proximal and distal nerve ends are available, the nerve can sometimes be reconstructed, potentially restoring some sensation and function.

What else can Neuroma be?

There are also other types of non-cancerous tumors that can develop on the peripheral nerves, including:

- Ganglion cyst

- Intraneural heterotopic ossification

- Sarcoid granuloma

- Inflammatory pseudotumor of nerve

- Leprous neuropathy

- Hypertrophic neuropathy

- Lipofibromatous hamartoma

- Neuromuscular choristoma

What to expect with Neuroma

Making a quick and accurate diagnosis of nerve injuries is very important for better healing. This is especially crucial due to a narrow window of time during which a successful nerve repair or surgery can be carried out. People with traumatic neuromas—a type of nerve injury—often experience a poor quality of life. This can be due to discomfort, long-term pain that can last from weeks to years, and related mental health issues.

After digit amputation—which refers to the removal of fingers or toes—about 6% of people will go on to develop a neuroma. However, if operated on at the time of the injury, this risk can drop to 1%. Neuromas, although not cancerous, can still cause problems by growing in size, increasing pain, and becoming stuck to nearby tissue.

Right now, there aren’t any studies that are checking if traumatic neuromas can shrink on their own. There are, however, studies looking at similar conditions like acoustic neuromas—another type of nerve tumor. These studies show about a 4% chance of these tumors shrinking on their own, leading some patients to choose careful monitoring instead of surgery.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Neuroma

A neuroma is a condition that causes severe pain, usually to the point where surgery is needed. The surgery can result in complications such as infection, bleeding, scars, and risks linked to anesthesia. It’s also worth noting that neuromas often return after surgery. Other complications from a neuroma could include long-term disability, chronic pain that lasts from weeks to years, and emotional health problems.

Common Complications:

- Severe pain

- Surgical complications like infection and bleeding

- Scarring

- Anesthetic risks

- Neuroma often comes back after treatment

- Long-term disability

- Chronic pain lasting weeks to years

- Emotional health problems

Recovery from Neuroma

Dressings are an important part of the healing process for wounds. When it comes to repairing nerves, it usually happens without any strain. This means that there’s generally no need to safeguard the repair with something rigid, like a brace or plaster. All that’s typically needed is a larger, or ‘bulky’, dressing.

Preventing Neuroma

Traumatic neuromas, a type of tumor, can affect a patient’s quality of life. Since there is not a widely agreed-upon management strategy for this condition, the main focus is on preventing its occurrence. More information on prevention strategies can be found in the “Treatment” section.