What is Basilar Invagination?

Basilar invagination (BI) was first identified in cretins by a scientist named Ackermann. The condition was then diagnosed using radio imaging by Schuller, a method later refined by Chamberlain and other radiologists.

Simply put, basilar invagination is an unusual condition at the junction of the skull and spine. It can be present from birth, or develop over time due to degeneration. This abnormality results in a small, tooth-shaped part of the spine encroaching on the very narrow opening at the base of the skull, known as the foramen magnum. Basilar invagination is often found in combination with other conditions like Chiari malformation, syringomyelia, and Klippel-Feil syndrome. Symptoms vary but can include chronic headaches, restricted neck movement, and sudden worsening of neurological function.

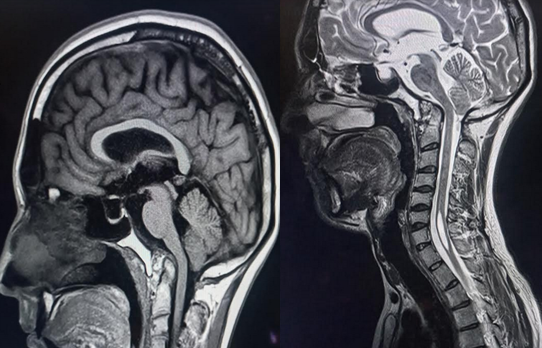

CT and MRI scans are extremely important in diagnosing and managing basilar invagination. These scans are also very useful for surgical planning, if surgery is needed.

The debate continues on whether surgery is needed for patients with basilar invagination who have no symptoms. However, those who are at risk of worsening neurological function could require a special type of neck brace before surgery, and a carefully planned surgical approach.

What Causes Basilar Invagination?

When it comes to bone growth, changes in the neck bones are more significant from birth until full growth than other parts of the spine. Some abnormalities may seem unchanging, but abnormalities in the neck spine are more likely to become painful and can even be life-threatening.

The most common abnormalities in the area where the skull and neck meet in adults include Chiari malformations and basilar invagination. Basilar invagination is a condition that develops when the base of the skull at the large opening (foramen magnum) forms in a way that the top part of the neck bone extends higher and often to the back, causing a narrowing at the large opening. This area is at risk of a bulging bone (odontoid prolapse) and a reduced available space, increasing the patient’s risk for nerve injury or disruption of the flow of cerebrospinal fluid. This condition could result from instability of the first two neck bones, a birth defect in the bone, or due to wear and tear conditions – like it happens in 20% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Basilar Invagination

Basilar invagination (BI) is found to be the most common type of craniovertebral junction malformation, a condition that affects the point where the skull and spine meet. One study showed it to be the most frequently occurring anomaly, affecting over half of the young adults with these types of malformations.

Another study revealed a potential connection between BI and a condition known as a Chiari malformation, particularly when looking at patients who had undergone surgery for BI. They found that those with a Chiari malformation usually started showing symptoms later in life and had a slower progression of symptoms. These individuals commonly experienced issues like weakness, ‘pins and needles’ sensations, problems with their senses of position and pain, and lack of coordination. On the other hand, those without the Chiari malformation typically started showing symptoms earlier in life and had symptoms like weakness, neck pain, issues with their sense of position, problems with their bladder and bowel function, and ‘pins and needles’ sensations. Interestingly, nearly half of the patients without a Chiari malformation reported that their symptoms started after a traumatic event, while none of the patients with a Chiari malformation reported a history of trauma.

- Basilar invagination (BI) is the most common type of craniovertebral junction malformation.

- BI was the most common anomaly in a study on young adults with craniovertebral junction malformations.

- A Chiari malformation might be linked to BI and could impact when symptoms begin and how they progress.

- People with a Chiari malformation usually started showing symptoms later in life and symptoms progressed more slowly.

- Common symptoms for people with a Chiari malformation included weakness, ‘pins and needles’ sensations, problems with senses of position and pain, and lack of coordination.

- People without a Chiari malformation usually started showing symptoms earlier in life with weakness, neck pain, positional sense issues, bladder and bowel problems, and ‘pins and needles’ sensations.

- Nearly half of the patients without a Chiari malformation reported that their symptoms started after a traumatic event, but none of the patients with a Chiari malformation reported a history of trauma.

Signs and Symptoms of Basilar Invagination

Basilar Invagination (BI) can present itself in many ways, often linked to the associated conditions it’s related to. For example, a Chiari malformation can cause BI 33% to 38% of the time. The seriousness of the BI often depends on how much the dens-atlas-clivus part of the brain shifts upwards. This shift can cause a significant crowding at the base of the skull and the medulla oblongata, an area of the brain. This crowding can block the flow of cerebrospinal fluid, leading to a condition called syringomyelia. If the medulla oblongata isn’t working properly, a person could display symptoms like unsteady movements, lack of coordination, irregular eye movements, difficulty swallowing or facial nerve issues.

There is an interesting link between BI and headaches brought on by exertion, such as coughing (commonly felt at the back of the head, not migrinely). A study found brain abnormalities in 45% of 97 patients dealing with cough, exertional, or sexual headaches. In fact, up to 80% of these headaches were linked to Chiari I, a form of BI. As a result of their findings, researchers recommended that every patient with a cough-induced headache should have an MRI scan of the junction between the head and neck. These headaches can also be triggered by laughter, weight lifting, or if the head changes position. Other noticeable signs include a short neck (found in 78% of cases), asymmetrical face/skull, or twisted neck (found in 68% of cases).

A common cause of BI is rheumatoid arthritis. The form of BI caused by rheumatoid arthritis was nicknamed “cranial settling”, as the shift of a part of the vertebrae, called the odontoid, is thought to be due to the head sinking because of eroded structures in the neck. About 8% of people with rheumatoid arthritis show these changes, which can lead to death due to instability and require surgical fixation.

BI can lead to various symptoms:

- Weakness

- Numbness

- Paresthesia (tingling or numb sensation)

- Neck pain

- Gait instability

- Spasticity

- Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing)

- Dysarthria (unclear or slow speech)

About 80% of patients present with neck pain, and torticollis (twisted neck) is observed in about 40% of patients. Some patients experience symptoms suddenly, while others find them progress slowly. Almost 60% of patients with a certain type of BI have a history of head injury prior to the onset of their symptoms. The neck might appear shorter and twisted in these cases. They might also experience neurological symptoms due to direct pressure on the brainstem by a part of the vertebrae called the odontoid process. Dysfunction in certain parts of the medulla oblongata can lead to shrinkage of the cerebellum while maintaining the tonsil volume. Other patients experience a set of symptoms called central cord syndrome and syringomyelia, caused by a crowded base of the skull.

BI can coexist with other conditions such as:

- Atlantoaxial dislocation

- Chiari malformation

- Atlas occipitalization

- Klippel-Feil syndrome

- Atlanto-occipital hypoplasia

- Clival hypoplasia

- Os odontoideum

- Platybasia

In an attempt to naturally protect itself when there is chronic instability in the uppermost vertebra, the spinal segments compress each other. This results in:

- Short neck

- Torticollis

- Dorsal kyphoscoliosis

- Klippel-Feil alteration

- C2–3 fusion

- Assimilation of atlas

- Bifid arches of atlas and axis

- Platybasia

- Chiari formation

- Syringomyelia

However, these changes can often be reversed after stabilising the uppermost vertebra in one type of BI or decompression of the foramen magnum in another type of BI.

Testing for Basilar Invagination

Basilar invagination (BI) is typically confirmed through the parameters of several key lines on a CT or MRI scan of the head. These lines connect various points within the skull. Let’s break down these parameters:

1. Chamberlain’s line: This connects the back of the hard palate and the back edge of the large hole at the base of the skull, called the foramen magnum.

2. McGregor’s line: A line running from the back edge of the hard palate to the lowest part of the bone at the back base of the skull.

3. McRae’s line: This is a line that measures the front-to-back length at the foramen magnum.

If the uppermost part of a bony spine in the neck, known as the dens, extends more than 5mm above Chamberlain’s Line, 7mm above McGregor’s Line, or interferes with McRae’s line, then BI is diagnosed. There are different types of BI, depending on certain measurements such as the Atlantodens interval (ADI), and the position of the odontoid process, which is part of the second cervical vertebra.

There are a number of other measurements and angles that are assessed when examining patients for BI. For example, analyzing the length and angle of the clivus, a bony part of the skull, can help understand the nature of the BI. Other elements such as clivus slope, the angle made between certain anatomical lines, and the size and angle of certain structures in the neck and skull are all used to aid diagnosis.

Some radiographic features, like the clivopalatal angle, can help guide surgical treatment if needed. It is also possible to use these measurements to predict how well a patient with BI might recover.

Medical imaging, in particular dynamic CT scans and multi-positional MRIs, play a very important role in understanding the health condition of patients with BI, as they provide key details on abnormal bone patterns, the extent of damage, and the paths of important blood vessels. The thickness and stiffness of the bones at the top of the spine and around the brain are also indicators of BI.

Before undergoing any surgery, a CT angiography scan (CTA) is strongly recommended. This would help identify any variations in the arteries of the neck, and therefore avoid any surgical complications. An advanced rendering technique can also be used to map out the path of these arteries for extra safety. The MRI is especially good at identifying where nerve compression occurs, spotting changes in fluid-filled cavities in the brain, and any additional conditions that might be associated with BI.

Treatment Options for Basilar Invagination

In 1939, Chamberlain first detailed a surgical method to treat basilar invagination (BI), a condition where the top of the second vertebra moves up into the skull. This complicated procedure involved cutting into the back of the skull and neck and opening the protective layer around the brain and spinal cord. However, it had a high risk of serious complications and even death, including the possibility of internal bleeding in the spinal cord.

Another method suggested using traction, applying a pulling force to the neck to control the disease’s progress. This approach was suggested for patients without major neurological issues. Pre-surgery traction can also give doctors a better understanding of the condition’s severity and the patient’s neurological status. Some research has shown that many patients experience significant improvement after receiving traction. It can also help decide whether the dislocation could be reduced during surgery or suggest potential risks during the procedure.

In 1980, surgical strategies evolved to classify craniocervical abnormalities into ones that could be reduced (brought back to normal position) and those that could not. Surgery through the mouth, initially introduced by Kanavel and later advanced with new instruments and technology, became a popular method to manage basilar invagination. However, surgeries like occipitocervical fixation, which stabilizes the junction between the skull and spine, have downsides like possible complications and significant restriction of head movements.

Over time, surgical techniques have further evolved from simple bone overlay around the affected area to sophisticated methods such as screw plate/rod fixation and facet fixation, which strengthens specific joints in the spine. Some cases with non-reducible deformity might require a unique distraction or removal procedure, either through an anterior (front) transoral (through the mouth) approach or a posterior (back) C1-2 facet distraction.

Deciding the best surgical approach should rely on a thorough evaluation of clinical findings and imaging studies. The purpose of surgical interventions includes decompressing the foramen magnum (the hole in the skull through which the spinal cord passes), restoring and stabilizing the craniovertebral junction, and returning normal cerebrospinal fluid flow dynamics.

Endoscopic endonasal approach (EAA), a new surgical method that uses the nasal passage to access the area, has shown advantages like earlier extubation (removal of breathing tubes), a lesser need for tracheotomy (making an incision in the windpipe), minimized risk of postoperative complications, earlier feeding post-operatively, and shorter hospital stays. Almost 90% of patients undergoing this procedure have shown neurological improvement.

However, EAA also has its share of disadvantages like a smaller working space, the challenge of handling surgical instruments, and difficulties in suturing, especially during a cerebrospinal fluid leak. There is also a steep learning curve for surgeons with this technique.

Posterior C1-C2 distraction and fixation have been proven to be an effective technique for treating basilar invagination, and more recently, a geometric model has been developed to better understand reductions in atlantoaxial dislocation and basilar invagination. However, the best surgical approach should always be determined on a case by case basis after careful examination.

What else can Basilar Invagination be?

“Platybasia” is a medical term that describes an unusual flattening of the base of the skull. It’s a term that was first introduced by a scientist named Virchow.

Another term, “basilar impression”, is sometimes also called atlantoaxial impaction or vertical cranial settling. This condition develops when the bone at the base of the skull becomes soft. A variety of conditions might lead to this softening, including:

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Paget’s disease

- Osteomalacia (softening of bones due to lack of vitamin D or a problem with the body’s ability to break down and use this vitamin)

- Hyperparathyroidism (overactivity of the parathyroid glands resulting in excess production of parathyroid hormone)

- Osteogenesis imperfecta (a group of inherited disorders characterized by easily broken bones)

- Hurler syndrome (a rare genetic disorder)

- Rickets (a disorder caused by a lack of vitamin D, calcium, or phosphate)

- Infections that affect the base of the skull

It’s thought that basilar impression might be due to repeated microfractures caused by regular axial loads on the skull. This theory is backed by findings during surgery showing growth of new bony tissue (proliferative callus) at the base of the skull in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Research has indicated that about 1 in 4 of these patients have this defect. This defect, even if treated later, may lead to severe outcomes in individuals with osteogenesis imperfecta and other bone and joint disorders such as Hajdu-Cheney syndrome.

What to expect with Basilar Invagination

Surgery can often help to improve neurological symptoms, but it is important to note that a full recovery may not always be attainable. It’s not uncommon for some neurological deficits to remain after surgery, and in some instances, these might be significantly impairing.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Basilar Invagination

There can be multiple causes for inadequate decompression such as, complicated bone structure in the region, severe slanting of the C1-C2 facets, and abnormal bone fusion. It’s important to note that the presence of spondylolisthesis (a condition where one vertebra slides over the one below it), severe facet joint disease, and contracting tissues may obstruct the ability to realign the spine.

As far as reducing AAD in BI, the key factors that can limit this include the tension band in the anterior atlantoaxial region, and deformation of the lateral articular process.

There are also several complications associated with different spinal procedures:

Complications of the transoral approach:

- Damage to the eustachian tube and hypoglossal nerve

- Bleeding

- Severe tongue swelling

- Palatal and pharyngeal dehiscence

- Retropharyngeal abscess

- Neurological worsening

- Inhaling food or liquid into lungs

- CSF leak

- Meningitis

- Delayed pharyngeal bleeding

- Craniovertebral junction instability

Complications of craniovertebral junction fusion surgery:

- Neurological worsening

- Injury to the vertebral artery

- Bleeding

- Craniovertebral junction instability

- Spinal cord swelling

- CSF leak

- Meningitis

- Failure of bones to grow together

- Failure of surgery hardware

- Sudden death

Common complications of posterior fusion surgery:

- Mechanical failure such as bones not fusing, instrument failure, and nearby segment degeneration. The C1–2 facet joint is critical for good fusion and undertaking kyphotic correction.

- Subaxial kyphotic deformity seen after laminoplasty and wider detachment of deep extensor muscle. So, it is crucial to avoid occipital fixation to minimize such risk and to ensure the preservation of C0–1 motion.

- Frequently, after C2 root resection, occipital neuralgia can occur, but it generally does not substantially affect patient-reported outcomes or quality of life.

Neurological worsening is commonly seen during vertical reduction. The risk increases in patients with T2 signal changes in MRI and reduced canal diameter. However, this can be prevented with the assistance of intraoperative neuromonitoring (IONM). Lastly, Dysphagia which is difficulty swallowing can especially occur following the “military tuck” positioning that can lead to glossoptosis (downward displacement or retraction of the tongue). The risk is further increased in those patients with OC fixation in retraction posture.