What is Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder (NMOSD)?

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is a condition that was in the past known as neuromyelitis optica or Devic disease. This condition was first identified by Dr. Eugene Devic in 1894 while he was examining a patient who had optic neuritis (inflammation of the optic nerve) which led to muscle abnormalities (see Image 1. Neuromyelitis Optica). Dr. Devic’s student, Fernand Gault, published a review of similar medical cases that same year, including the findings from Dr. Devic’s case. For a long time, multiple sclerosis (MS) was believed to be the primary autoimmune disease that resulted in optic neuritis. However, recent findings have pointed to less common but potentially more dangerous autoimmune diseases which can also cause optic neuritis, such as NMOSD and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody disease (MOGAD), a rare disorder that attacks the protective covering of nerves.

With newer research, our understanding of neuromyelitis optica has expanded. Scientists discovered a specific antibody—a protein that the immune system uses to fight off harmful substances—in the blood of patients with this condition. They’ve also identified various symptoms linked to a range of diseases. Therefore, the term neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is now used. NMOSD encompasses optic neuritis, spinal cord symptoms, and other neurological disorders related to the presence of an antibody known as aquaporin-4 immunoglobulin G (AQP4-IgG) in the blood.

What Causes Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder (NMOSD)?

The exact cause of NMOSD, a rare neurological condition, isn’t entirely understood. In the past, doctors thought NMOSD was a type of Multiple Sclerosis (MS), a disease that affects the nervous system. However, recent research shows that NMOSD has different causes, symptoms, and treatments compared to MS.

Recent advancements in genetics have discovered some genes that might increase a person’s risk of developing NMOSD. Among these are a group of genes known as major histocompatibility complexes (MHCs), particularly one named HLA-DRB1*03:01.

Interestingly, the genetic makeup of NMOSD seems to have more similarities with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) – an autoimmune disease where the body’s immune system attacks its own tissues and organs, rather than MS.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder (NMOSD)

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, or NMOSD, is a type of illness that’s not very common, as its prevalence ranges from 0.3 to 4.4 for every 100,000 people. The disease mostly affects women (80%) between the ages of 30 and 40. Although instances of NMOSD in children are quite rare, they do occur and make up less than 5% of the total cases. The disorder is seen worldwide, but most information we have comes from countries with better economic conditions, probably because these countries have better healthcare resources like MRI machines and specialized antibody tests.

Interestingly, the prevalence of NMOSD varies significantly in different parts of the world. For instance, it represents just 1-2% of demyelinating diseases in the United States and Italy, but makes up 13.7% of cases in India and over 30% in Thailand. Ethnicity also seems to affect the symptoms and course of the disease. In a study conducted in Cuba, patients of African heritage were found to be older at the onset of NMOSD, had more visible damage in MRI scans, and experienced more relapses compared to patients of other ethnicities.

These patterns in the occurrence and presentation of NMOSD might help doctors when they’re trying to diagnose the disease, especially when considering patients of Asian or Indian background, or older patients of African heritage. NMOSD is sometimes accompanied by other autoimmune diseases like lupus, celiac disease, and Sjögren syndrome. In 20-30% of NMOSD cases, the disease seems to be brought on by an environmental trigger, such as vaccination or infection.

Signs and Symptoms of Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder (NMOSD)

Optic neuritis is a condition that causes sudden, painful loss of vision in one eye. It’s usually identified by an affected pupil that doesn’t respond well to light. Medical professionals will check vision sharpness, pupil response, eye pressure, and perform a detailed check of the nervous system connections to the eyes. An exam of the back of the eye may show swelling of the optic nerve. Some less common, but serious causes of optic neuritis are NMOSD and MOGAD. If patients are having symptoms like constant hiccups, unexplained nausea or vomiting, or extreme daytime sleepiness (narcolepsy), these conditions may be the cause of the optic neuritis.

NMOSD doesn’t always present in a traditional way and can also appear in other disorders, like isolated inflammation of the spinal cord, inflammation of the brainstem, single or recurring optic neuritis. A patient with brainstem symptoms (like ongoing hiccups, vomiting, or narcolepsy) should have a full neurological check. Usually there is vision loss in both eyes and complete or partial paralysis caused due to bilateral optic neuritis and inflammation of the spinal cord. However, optic neuritis and spinal inflammation may not occur at the same time.

NMOSD does not usually show up just once, but rather it follows a pattern of multiple flare-ups over time, often with long periods in between. Concurrent features of conditions like lupus, myasthenia gravis, autoimmune thyroid disease, Sjögren’s syndrome, and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome may be present.

Here are the key symptoms of NMOSD in adults:

- Optic neuritis (inflammation of optic nerve)

- Acute myelitis (inflammation of spinal cord)

- Area postrema syndrome (unexplained hiccups, nausea, or vomiting)

- Acute brainstem syndrome

- Symptomatic narcolepsy or acute diencephalic clinical syndrome with NMOSD-typical diencephalic MRI lesions

- Symptomatic cerebral syndrome with NMOSD-typical brain lesions

Testing for Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder (NMOSD)

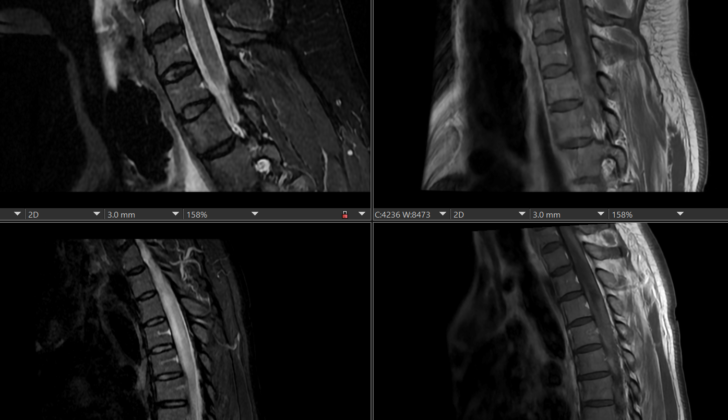

NMOSD, also known as neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, is a condition evaluated using clinical examinations, blood tests for a specific antibody called AQP4-IgG (Aquaporin 4 Immunoglobulin G), and two types of MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) scans – one with and one without a dye called gadolinium. The diagnosis is mainly based on the essential symptoms you’re experiencing and other test results. In 2015, experts agreed on international criteria to diagnose NMOSD. These diagnostic rules acknowledge whether AQP4-IgG is tested or not, and also define typical clinical and MRI signs for NMOSD.

Some people with NMOSD may experience issues with color vision, and field of vision tests might reveal a blind spot in the center of the visual field. Additional tests, such as optical coherence tomography, can help in the diagnosis and might reveal thinning around the optic nerve, which is different from what is often seen in multiple sclerosis (MS) cases.

MRI scans with and without gadolinium are useful tools in evaluating NMOSD. Common signs in people with optic neuritis – a condition that affects the eye nerves and is common in NMOSD – include white matter brain lesions and enhancements of the optic nerve on MRI. Other typical MRI signs of NMOSD are inflammation of the spinal cord, with either long lesions in the spinal cord or areas of spinal cord shrinkage.

It’s common for both optic nerves to be involved in NMOSD, especially if the back portion of the optic nerve is affected, which extends to the optic chiasma (where the optic nerves cross). This is a strong hint towards NMOSD. In the chronic stages, the optic nerve may shrink, and MRI scans may show bright signals on T2 images.

The condition can also cause brain lesions found around the ventricles – fluid-filled spaces in the brain – in areas where the aquaporin-4 protein is located. Other imaging findings could include lesions in the deep parts of the brain, large brain lesions without swelling, as well as lesions in the corticospinal tract.

In NMOSD, differentiation from multiple sclerosis (MS) is very important because the management and prognosis of the two conditions are substantially different. Some medications used for MS can, in fact, make NMOSD worse. There are unique features in NMOSD that help to distinguish it from MS. For instance, spinal cord lesions in NMOSD usually extend over three or more segments, unlike in MS where the lesions are typically shorter and there are many of them.

Also, round, intensely bright lesions in the central part of the spinal cord that appear darker on T1 images are indicative of NMOSD. In the acute phase, these lesions are often enhanced during MRI when gadolinium contrast is used.

Treatment Options for Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder (NMOSD)

NMOSD, which stands for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, is a condition that doesn’t occur often, so it’s a bit difficult to create a standard guideline for treating it. However, most of the time, treatment follows a two-step process. First, a short course of immunosuppressive therapy is used, which is designed to reduce the activity of the body’s immune system. This therapy usually involves corticosteroids, a type of medicine that reduces inflammation. Second, a long-term immunosuppressive therapy is given.

When a person with NMOSD experiences a flare-up of symptoms, which is also known as an acute phase, treatments typically include intravenous steroids. Intravenous means the steroids are delivered directly into a vein, usually through a drip. One common type of steroid used is methylprednisolone. Plasmapheresis, a procedure that filters the blood, or intravenous immunoglobulin, an antibody treatment, might also be recommended in some cases.

The long-term immunosuppressive therapy involves medicines like azathioprine or rituximab. If these aren’t suitable, alternatives like mycophenolate or methotrexate might be given. These are called second-line agents and can be beneficial because they need to be taken less frequently. There are also newer medicines that target specific parts of the immune system, like anti-IL-6, anti-complement or anti-AQP4-IgG.

Data from a careful look back at patient cases has shown that the rate of having more episodes of symptoms was reduced by 88.2% with rituximab, 87.4% with mycophenolate, and 72.1% with azathioprine (when also given with prednisone).

Another crucial point in the treatment of NMOSD is that it’s important to distinguish it from multiple sclerosis, abbreviated as MS. This is because some medications used for MS, including natalizumab and beta-interferon, can make NMOSD worse.

What else can Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder (NMOSD) be?

When a patient shows symptoms of optic neuritis, doctors usually consider the following conditions:

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

- Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder (NMOSD)

- Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody Disease (MOGAD)

Of these, MS is the most common and is usually ruled out first. NMOSD and MOGAD are rarer, often have less favorable outcomes, and require different treatments.

MOGAD is an uncommon condition where antibodies attack a protein (MOG) necessary for the nervous system. While MOGAD often has only one phase, recurrent optic neuritis can occur. The MRI for a patient with MOGAD can reveal various unique features, such as lesions in deep gray matter of the brain and long segments of spinal cord being affected.

NMOSD, another condition often considered, can present without any eye symptoms, making it more difficult to identify. The main condition doctors look for when suspecting NMOSD is MS, but any condition that causes similar symptoms to MS could potentially be the culprit.

Significant differences between NMOSD and MS include:

- Prevalence: NMOSD is rare while MS is common

- Gender: NMOSD affects women more, as does MS, but less so

- Ethnicity: NMOSD is common in Asians and Blacks, MS in Whites

- Effects on eyesight: NMOSD often causes severe vision loss with little improvement, while MS generally causes moderate visual loss with vision usually improving considerably

- Progression: MS often worsens over time, while NMOSD does not

- Affected areas: NMOSD affects both white and grey matter, MS primarily affects white matter

The differences in how the diseases appear on MRI scans and the results of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis are also valuable in diagnosis. For example, NMOSD usually affects a larger segment of the optic nerve and shows higher protein content in CSF analysis, compared to MS which affects a smaller segment of the optic nerve and has lower protein content in CSF analysis.

What to expect with Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder (NMOSD)

NMOSD, a health condition, varies greatly in how it affects different people and how long it lasts. In 80% to 90% of people, this condition goes through cycles of symptoms, or ‘relapses’. Unfortunately, some people end up living with a long-lasting disability as a result of these relapses.

Studies have found up to 22% of patients completely recover, but sadly, 7% show no recovery at all. Those with NMOSD that goes through cycles of symptoms usually have a worse outlook.

About 52% of patients with recurring symptoms experience paralysis in one or both legs, compared to 31% of patients with symptoms that only occur once. In addition, around 60% of patients with a recurring form of the disease end up with vision loss in one or both eyes, compared to 22% of those whose symptoms only occur once.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder (NMOSD)

The adverse effects of Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder (NMOSD) vary. They can range from visual disturbances and muscle weakness to permanent blindness and irreversible muscle loss. In critical cases, this disease can lead to breathing difficulties due to muscle failure, adding to the risk of death.

Potential Complications:

- Visual disturbances

- Muscle weakness

- Permanent blindness

- Irreversible muscle loss

- Respiratory failure

- Increase in risk of death

Preventing Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder (NMOSD)

If a patient is diagnosed with NMOSD (neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder), it’s important they understand the possible complications of this condition. They should also be aware of related autoimmune conditions, which are disorders where the body’s immune system attacks healthy cells. The importance of taking prescribed medications correctly and having regular health check-ups is also crucial for managing this condition. It’s worth noting that at present, there are no known methods for preventing NMOSD.