What is Anorexia and Cachexia?

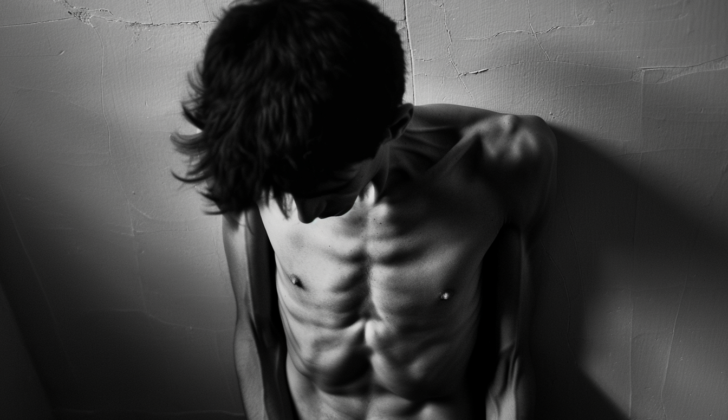

Cachexia is a serious condition where a person loses a lot of their muscle and fat tissue. It often happens to people with severe health conditions like advanced cancer, chronic lung disease, chronic infections like AIDS and tuberculosis, chronic heart failure, and rheumatoid arthritis. Cachexia is marked by a rise in factors that cause inflammation. It lessens the quality of life, weakens the body’s ability to withstand surgery or medical procedures, and shortens lifespan.

The likelihood and severity of cachexia can vary depending on the type of cancer. It is more commonly found in patients with cancers of the stomach, pancreas, and lungs, while it is less frequent in patients with breast cancer, sarcomas, and blood-related malignancies.

Cachexia is different from just being malnourished or starving. Instead of using glucose as the main source of energy, the body turns to fat stores in this condition. This shift in metabolism is brought on by cancer and conventional nutritional supplements or diet are not enough to treat the problem.

What Causes Anorexia and Cachexia?

Cachexia, often associated with cancer, is a complex condition that consists of three components:

- Metabolic imbalances

- Lack of appetite (anorexia)

- Dysfunction of the digestive system

This condition can be triggered by the disease itself, treatment side effects, or emotional distress, and symptoms may include nausea, a lack of hunger, and distorted taste perception.

An essential part of cachexia is cytokines. These are substances like tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukins 1 and 6, ciliary neurotrophic factor, leukemia inhibitory factor, and interferon (IFN)-gamma, among others. They are produced by both tumor cells and the body’s immune cells. These cytokines contribute to weight loss, protein and fat breakdown, a decrease in insulin levels, a rise in stress hormone levels, and increased energy expenditure.

Healthy immune cells and many tumors produce these cachexia-causing cytokines. They can lead to increased energy use and loss of muscle mass. These factors don’t necessarily correlate with the amount of weight loss and lack of appetite experienced by cancer patients, suggesting there may be a central mechanism at work.

The chemicals serotonin, insulin, and ghrelin, along with disruptions in brain circuits, may be involved. For example, high levels of serotonin, which can result from elevated tryptophan levels in patients with cancer and a lack of appetite, may contribute to this condition.

Meanwhile, the digestive tract may also fluctuate in function. Tumors in various parts of the digestive system can impact oral food intake, and intestinal obstruction is common. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy can cause various side effects, including nausea and changed tastes and smells, which can also contribute to cancer-related cachexia.

Finally, changes in metabolism and biochemistry, such as cancer cells’ heightened glucose use and their production of lactic acid, may further stir up cancer-related cachexia. Tumor-related metabolic changes and the tumor’s environment could vastly contribute to this condition.

Several theories suggest potential causes for the lack of appetite in cancer, including various cytokines, lactate levels in the blood, neuropeptides, some chemotherapy agents, high calcium levels in the blood, and various hormones.

Lastly, several compounds, drinking and eating related hormones, are believed to hold a significant role in cancer-related cachexia. These include both those that stimulate hunger (orexigenic molecules) like hypocretin, ghrelin, and neuropeptide Y, and those that dampen hunger (anorexigenic molecules) like insulin, leptin, and serotonin.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Anorexia and Cachexia

Cachexia, a condition characterized by muscle loss and weight loss, is found in varying amounts in different diseases. It’s seen in about 5% to 15% of people with congestive heart failure (CHF) or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and a much higher 60% to 80% of people with advanced cancer. The mortality rate of patients with cachexia varies widely depending on the underlying disease. In COPD patients with cachexia, the mortality rate annually is 10% to 15%. For those with cachexia alongside CHF or chronic kidney disease, the yearly mortality rate is between 20% and 30%. However, in patients with cachexia due to advanced cancer, the mortality rate goes up to 80%.

Signs and Symptoms of Anorexia and Cachexia

Cancer cachexia is a condition that can be defined by several key indicators. These include a weight loss of more than 5% over the course of a year, a Body Mass Index (BMI) of less than 20, or the presence of sarcopenia, which is a condition of muscle loss verified by a specific type of body scan called dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

Testing for Anorexia and Cachexia

Checking on a patient with cachexia – a condition causing extreme weight loss and muscle wasting – involves tracking changes in their blood chemistry and body weight. A method called bioelectrical impedance is often used for this purpose.

Cancer cachexia is seen in different stages:

- Pre-cachexia: This is when the patient has a loss of appetite and changes in metabolism, with a weight loss of 5% or less.

- Cachexia: In this stage, the patient’s Body Mass Index (BMI) is below 20, and weight loss is more than 2%. It can also be a situation where the patient shows signs of systemic sarcopenia – a loss of muscle mass – and their weight loss is more than 2%.

- Refractory cachexia: This final stage is marked by the cancer not responding to treatment, a low level of physical activity, and an expected survival time of less than 3 months.

Treatment Options for Anorexia and Cachexia

The best cure for cancer cachexia is typically removing the tumor. However, if the tumor can’t be removed, there are various options that show promise.

One important strategy is taking care of the patient as soon as possible. Providing early nutritional support can improve a patient’s health and may reduce inflammation. Maintaining a stable body weight during chemotherapy can lower harmful side effects and increase survival rates. Several methods could be beneficial, including anti-nausea medication, pancreatic extracts, small, frequent meals, homemade food supplements that might be easier to tolerate, oral and injected nutritional supplements, treatment for mouth sores, and blood transfusions.

Exercise is another key factor. Even during active cancer treatments, exercise is safe and beneficial. This physical activity can improve muscle strength, bone health, and reduce levels of depression, fatigue, and stress. Also, physical activity can lessen the impact of other health issues that affect cancer survivors. Research shows that exercise can lower the overall death rate, improve insulin sensitivity, alter muscle metabolism, and decrease inflammation.

There are also several drugs and supplements that can help. For instance, olanzapine, a drug that acts on serotonin and dopamine receptors, has shown promise in improving weight and nutritional status at low doses. Other medication and supplements can also be used, such as ghrelin and its analogs like anamorelin, anabolic-androgenic steroids like nandrolone decanoate, and thalidomide, an inflammation-reducing medication often combined with other drugs.

In addition to these, there are drugs used to manage the symptoms of cachexia. These include megestrol acetate, which improves appetite; metoclopramide, which improves stomach emptying; and dronabinol, which can enhance appetite, although it hasn’t been as effective as some other options.

As researchers continue to learn more about cancer cachexia, they are investigating new potential treatments. This includes bimagrumab, a drug that’s being tested for lung cancer-related cachexia; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); hydrazine sulfate, an enzyme that disrupts the body’s sugar production; and beta-hydroxy-beta-methyl butyrate combined with L-arginine and L-glutamine.

However, it’s important to note that not all of these approaches have proven to be beneficial for all patients, and some treatments carry their own risks and side effects. As with any medical treatment, it’s crucial to discuss all options with your doctor to determine the most effective and appropriate approach for you.

What else can Anorexia and Cachexia be?

Doctors consider a variety of different conditions when trying to diagnose the causes of severe weight loss and loss of appetite, also medically known as anorexia and cachexia. Potential causes could include:

- Achalasia (a rare digestive disorder)

- Avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (an extreme lack of interest in food or avoiding foods based on their smell, texture or color)

- Binge eating disorder (consuming large amounts of food in a short period of time)

- Cancer

- Constipation

- Crohn’s disease (a type of inflammatory bowel disease)

- Cystic fibrosis (a genetic disorder that affects the lungs and digestive system)

- Dementia (a group of conditions associated with a decline in cognitive skills)

- Tuberculosis (an infectious disease primarily affecting the lungs)

- Hypothyroidism (a condition where your thyroid doesn’t produce enough hormones)

- Irritable bowel syndrome (a common disorder that affects the large intestine)

- Multiple sclerosis (a disease affecting the central nervous system)

- Panhypopituitarism (a condition where the pituitary gland doesn’t produce enough hormones)

- Protein-losing enteropathy (a condition characterized by the loss of protein from the digestive tract)

- Rheumatoid arthritis (a chronic inflammatory disease that typically affects the small joints in your hands and feet)

Through careful examination and tests, doctors can narrow down the potential causes to correctly identify the root cause of the weight loss and loss of appetite.