What is Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome?

Knee pain can limit movement and reduce the quality of life for 1 in 4 adults. One possible reason for this is Iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS), a condition that often causes pain on the outer side of the knee. ITBS was first noticed in US Marine Corps recruits during their training in 1975 and is frequently seen in long-distance runners, cyclists, skiers, and those involved in hockey, basketball, and soccer. These activities involve repetitive bending and straightening of the knee, which can lead to ITBS. In this article, we’ll explain how these movements can cause ITBS, and we’ll talk about how to identify and treat the condition.

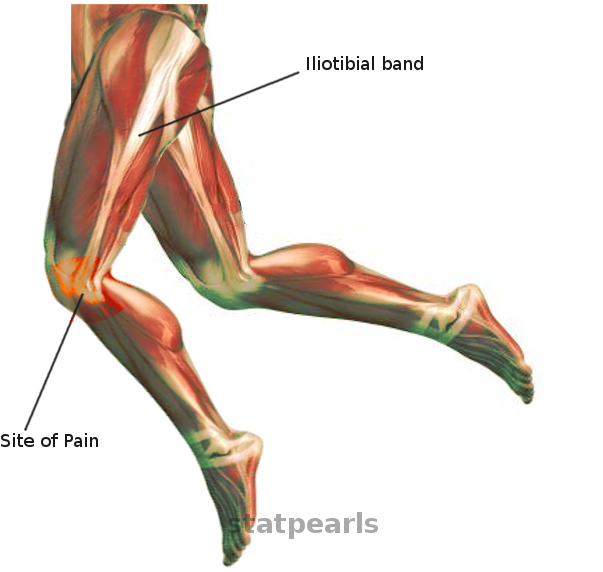

The iliotibial band (ITB) is a part of your leg made up of a combination of tissues from the tensor fascia lata, gluteus medius, and gluteus maximus muscles. It runs superficially (on the surface) over the vastus lateralis muscle (the outer part of your thigh) and attaches to the Gerdy’s tubercle on the outer part of your knee and partially to the supracondylar ridge of the femur (thigh bone).

There’s also a front extension of the ITB called the iliopatella band that connects to the outer side of the kneecap, helping ensure it doesn’t move too far over to the inner side. The ITB helps to straighten the knee when it’s bent less than 30 degrees but becomes a knee bender after it exceeds 30 degrees of bending. It’s thought that the ITB moves to a more backside position relative to the outer projection (epicondyle) of the femur as the knee bends more.

What Causes Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome?

The exact cause of ITBS, or Iliotibial Band Syndrome, is still under debate and it’s likely that there are multiple factors contributing to it. One theory suggests that the repeated rubbing of the Iliotibial Band (ITB) and a bone in the thigh during bending and stretching can lead to inflammation in the area where they contact. This contact happens at a specific bend of the knee, called the “impingement zone.”

However, other studies have shown that this specific rubbing motion may not be fully responsible. Instead, the problem might lie with a fat pad located beneath the ITB that is highly sensitive to pressure. Compressing this fat pad may result in the pain commonly associated with ITBS.

Another theory suggests chronic inflammation of a fluid-filled cushion (called a bursa) located between the ITB and the bone in the thigh can lead to ITBS. It’s currently unclear if one of these theories is the main cause, or if ITBS is a result of several factors.

There are some risks factors for ITBS that can be modified or changed. These include running on a slanted surface, running uphill, incorrect training techniques, and sudden changes in how hard you train. Certain physical features, such as a twisted shin bone, weak hip muscles, excessive foot pronation (when your foot rolls inwards as you walk or run), and arthritis in the inner part of your knee that can cause it to bow outwards, can also contribute to ITBS as they can create extra strain on the ITB.

ITBS is often associated with pain at the top of the thigh bone due to changes in hip movement and increased tension at the top of the fascial complex, which is a band of connective tissues. Additionally, patellofemoral syndrome, a condition that causes knee pain, is commonly seen in people with ITBS due to the tension through the band that connects the hip and kneecap.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome

Iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS) is the main cause of knee pain on the outer side in runners and cyclists. However, it can also affect those engaged in sports like tennis, soccer, skiing, and weight lifting. The occurrence of ITBS varies from 1.6% to 12% in athletes who do a lot of repetitive motions. Although it’s a bit more common in women, ITBS mostly impacts active people and is rare in those who are not physically active. For example, military recruits have been found to have a 6.2% incidence rate of ITBS. Moreover, running and overuse injuries – like ITBS – account for 12% of the injuries in U.S. Marine Corps personnel.

Signs and Symptoms of Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome

Iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS) is a condition that often doesn’t require additional testing or images to diagnose. Doctors will take into account factors like any mechanical symptoms experienced by the patient, changes in physical activity, distance run during exercise, and the state of their running shoes. Symptoms generally occur in the area between the Gerdy tubercle and lateral epicondyle on the outer side of the knee. It’s common for this syndrome to present after a change in cardio exercises, and it’s unlikely to be caused by a sudden injury. At first, the pain might only appear after physical activity but can start to occur at the beginning of the activity and even at rest as the condition worsens. Certain running conditions such as an inclined surface or long strides can also increase symptoms.

Doctors use physical exams to diagnose ITBS. They’ll look for misalignments in the knee such as genu varum, genu valgum, recurvatum, and procurvatum since these conditions might increase ITBS tension. Patients with ITBS often don’t experience a swelled knee or lax knee ligaments. The doctor may feel crepitus (a crunching or grinding sensation) during physical examination, and pressing on the bottom of the ITB might be painful. Specific tests for ITBS include the Noble and Ober tests.

- Noble test: The doctor will locate the lateral femoral epicondyle on the patient’s knee, then extend the knee from a 90 degrees angle to a 0 degrees angle. If the patient feels pain at around 30 degrees of flexion, this indicates a positive test result.

- Ober test: The patient lies on their side with their knees bent to 90 degrees. The doctor will stand behind the patient, lift and extend the affected hip while supporting the knee. Then, the doctor reduces the hip in this extended position. Pain and restrictive movement in the outer knee confirms a positive test result.

Testing for Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome

If you have pain on the outer side of your knee, your doctor may recommend getting pictures taken of the inside of your knee to check for other possible causes of the pain. This could include things like arthritis, a fracture, or an issue with your kneecap not being aligned properly. This is usually done with a kind of x-ray known as a radiograph. If you have a condition called Iliotibial Band Syndrome (ITBS) – which is a common cause of knee pain – and there’s nothing else wrong, the x-ray will look normal.

If the doctor still isn’t sure what’s causing your pain even after talking to you about your symptoms and examining your knee, they may recommend getting a more detailed picture of your knee using a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan. If you have ITBS, the MRI might pick up on certain signs, like brightness (hyperintensities) at the outer bump of your knee (lateral epicondyle) and a thicker than normal Iliotibial Band (ITB – a band of tissue that runs down the outside of your leg).

Finally, a test called an ultrasound may also be used. This test is not very expensive and has low risk. If you have ITBS, the ultrasound might show that your ITB is abnormally thick at the part of your knee where it ends.

Treatment Options for Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome

If you’re suffering from Iliotibial Band Syndrome (ITBS), the main form of treatment usually doesn’t involve surgery. The first step is to take a break from any activities that may be causing your pain until it’s completely gone. Using cold packs can also help when the pain flares up. As soon as you’re no longer in pain, you can start doing physical activities gradually again.

Physical therapy can play a huge role in your recovery. Specific exercises help to stretch your ITB (a ligament that runs down the outside of the thigh), and to strengthen your hip muscles, reducing tension. Your therapist might also use techniques such as myofascial release – using a foam roller to massage and release tight muscles and ligaments. They can show you the right way to sit, stand, or move to avoid straining your ITB.

In addition to this, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can help reduce inflammation, and corticosteroid injections can provide both temporary and long-term relief. Your doctor may also recommend modifications to your shoes or insoles, and special training related to your sport, to help prevent the condition from returning. Most patients feel better and are able to get back to their normal activities within a 6-8 week period with these non-surgical treatments.

Your return to activity should be gradual. You can start off by running on flat surfaces, for a week, skipping a day in between. Then, if you’re comfortable, you can switch to running every day at a faster pace, making sure to avoid running downhill. If that goes well for 3 to 4 weeks, you can start increasing how far and how often you run. Adding inclines and uneven surfaces should only be done if there’s no pain when running on flat surfaces. If you start feeling pain again, you’ll need to take it easy and start from the beginning, and may need to rest before doing so.

Only in cases where normal treatments haven’t helped after more than 6 months do doctors consider surgery. There are a few different types of operations that can be performed, most of which involve making changes to the ITB. These could include making small cuts to the ITB, lengthening the ITB, or removing sections of it. Each of these methods have been successful in the past, but more research is needed to determine which is the best. Alternatively, a procedure can be performed to remove the fluid-filled sac underneath the ITB while leaving the ITB intact. Minimally invasive techniques can also be used to remove the area of tissue connecting the ITB to the thigh bone. Generally, patients have been satisfied with the results of these surgical options, and in one case, 97% of patients who had arthroscopy – a minimally invasive surgical procedure – reported positive results and were able to return to full activity.

What else can Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome be?

If you’re experiencing pain on the side of your knee, it could be due to a number of conditions. Here are the most common causes:

- Stress fracture of the outer part of the shin bone

- Tear in the outer meniscus (a type of cartilage in the knee)

- Arthritis in the outer part of the knee

- Strain in the ligament on the outer side of the knee

- Condition causing pain in the tendon of the biceps muscle of the thigh

- Pain radiating from an issue in the hip

- Patellofemoral syndrome, a condition causing pain in the front of the knee

- Condition causing pain in the tendon located behind the knee

What to expect with Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome

About 50% to 90% of patients usually get better within 4 to 8 weeks of non-surgical treatments. Similarly, all types of surgical treatments have shown good to excellent results. It’s important to note that ITBS, which stands for Iliotibial Band Syndrome, often follows a varying course – it can reoccur at any stage of the treatment process or even when returning to normal activities.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome

The main problem with ITBS (Iliotibial Band Syndrome) is that it tends to get worse over time. As the syndrome progresses, the person suffering may feel pain constantly, even when they are relaxing. ITBS is connected to the outer part of the knee; hence, its progression could cause patellofemoral syndrome, which is a problem relating to the kneecap and the front of the thigh bone.

Potential Problems:

- Constant pain, even at rest

- Patellofemoral syndrome due to progression of ITBS

Preventing Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome

Education about the condition and following the treatment plan carefully is crucial to effectively manage this health issue. It’s been observed that running faster and on flat surfaces can help reduce the amount of time the outer part of your thigh bone and the band of tissue running down the side of your thigh (lateral femoral epicondyle and ITB) come into problematic contact, or the “impingement zone”.

Frequent changes of footwear can also help because this prevents the soles from wearing unevenly, which could make the problem worse. Some patients might find working with a personal fitness trainer or physical therapist helpful in order to improve the way they move during sports or other activities.

It’s important to note that this condition, known as ITBS, can sometimes come back after you’ve returned to your regular activities. If this happens, you should go back to the beginning of the non-surgical treatment plan that was initially given to you.