What is Normochromic Normocytic Anemia?

Anemia is a medical condition where your body doesn’t have enough red blood cells, or these cells don’t carry sufficient hemoglobin, the component that carries oxygen to your body tissues and brings back carbon dioxide as waste. Fewer red blood cells mean less oxygen supply to your body, decreasing its capacity for appropriate gas exchange. This condition can occur due to blood loss, increased destruction of red blood cells, or decreased production of these cells. The level of anemia is typically measured by the ratio of packed red blood cells to total blood volume, which involves metrics like hematocrit and hemoglobin concentration.

Furthermore, anemia can be categorized based on the average volume of red blood cells, also known as mean corpuscular volume (MCV). Low MCV implies smaller than usual red blood cells, normal MCV indicates typical red blood cells, and high MCV signifies larger red blood cells. In general, anemia is defined as having less than 13.0 g/dL of hemoglobin in men and less than 12.0 g/dL in premenopausal women.

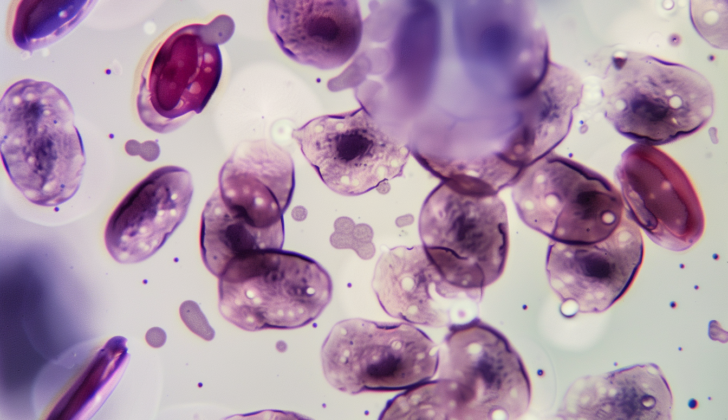

There’s a variant of anemia called normocytic normochromic anemia. Here, the red blood cells’ average size and hemoglobin content usually stay within the normal range, resulting in red blood cells looking normal under a microscope. However, sometimes, there might be variations in cell size and shape that offset each other, and the average remains normal. This form of anemia often arises due to chronic infections and certain systemic diseases. It mostly appears to result from an impaired production of red blood cells.

What Causes Normochromic Normocytic Anemia?

Normochromic, normocytic anemia mainly occurs as a result of other health conditions rather than being a primary blood disorder itself. Examples of these conditions include chronic diseases like inflammation or cancer, kidney failure, hormone (endocrine) system issues such as an underactive thyroid, bone marrow failure, quick loss of blood, or a disorder called polymyalgia rheumatica.

The exact cause of normochromic normocytic anemia, however, can vary. The cause depends on whether the body is not making enough new red blood cells (hypoproliferative, if the reticulocyte count is less than 2%) or it’s making too many (hyperproliferative, if the reticulocyte count is more than 2%).

If the reticulocyte count is normal or decreased, it could be because the bone marrow, which makes blood cells, is either normal or not working properly. If the bone marrow is normal, the cause of anemia could be chronic health conditions, kidney failure, certain hormonal disorders, liver disease, or early-stage iron-deficiency. If the bone marrow isn’t working properly, it could be due to the infiltration of the marrow (such as in leukemia), anemia because of a lack of proper development, medication side effects, or another condition called aplastic anemia.

If the reticulocyte count is increased, it could either be due to hemolysis, a condition where red blood cells break down too quickly, or hemorrhage, the medical term for bleeding. Hemolysis may be caused by inherent defects of red blood cells or other factors such as an autoimmune hemolytic anemia, a condition where your body’s immune system attacks and destroys your red blood cells. Hemorrhage, on the other hand, significantly reduces the number of red blood cells through blood loss.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Normochromic Normocytic Anemia

Normocytic normochromic anemia is a medical condition that can be caused by various factors. The most common cause is chronic diseases. A study conducted by Wiess et al. shows the estimated prevalence percentages of chronic diseases that cause this anemia as follows:

- Infections: 18% to 95%

- Cancer: 30% to 77%

- Autoimmune conditions: 8% to 71%

- Chronic rejection after solid organ transplantation: 8% to 71%

- Chronic kidney disease and inflammation: 23% to 50%

However, the occurrence of normocytic normochromic anemia in patients with less common causes like endocrine failure, marrow failure, and acute blood loss, is not well studied or understood.

Signs and Symptoms of Normochromic Normocytic Anemia

When diagnosing anemia, it’s important for healthcare professionals to take a thorough medical history. Symptoms associated with normocytic anemia may develop slowly, depending on the root cause.

Common symptoms include:

- Fatigue

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea)

- Difficulty with exercise

- General weakness

- Heart palpitations

- Headaches

- Difficulty concentrating

Important questions doctors may ask relate to:

- Your diet

- Any history of stomach pain or digestive problems

- Your medication use, especially regular use of NSAIDs (common pain-relievers)

- Any history of autoimmune conditions or cancer

- Any history of blood loss, including menstrual history

- Family history of conditions like thalassemia or sickle cell disease

Physical examination can also help confirm the diagnosis. Early signs of normocytic normochromic anemia, or any type of anemia, can include general weakness and a pale complexion.

During a physical examination doctors will look for:

- Pale skin, conjunctiva (the inner part of the eyelids), lips, palm lines, and nail beds

- Low blood pressure when you stand up after lying down

- Yellowing of the skin (jaundice) that might indicate hemolytic anemia

- Bone pain or enlarged organs, which could signal an infiltrative disease of the bone marrow

- Enlarged spleen, which could be a sign of conditions like lymphoma, leukemia, or myelofibrosis

Testing for Normochromic Normocytic Anemia

To diagnose a specific type of anemia called normocytic normochromic anemia, your doctor might order a series of tests. These could include a Complete Blood Count (CBC) to see the total number and types of cells in your blood. If there’s a sudden drop in your blood cell counts, the CBC would likely be repeated. But, if you’ve recently received lots of fluids, this could also impact your blood cell counts.

Your doctor may also require a test that looks at your Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV) and Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration (MCHC). These tests examine the average size of your red blood cells and the average amount of hemoglobin (the substance in your red blood cells that carries oxygen) in your blood.

A reticulocyte count is another important test. Reticulocytes are young, immature red blood cells, so this test can help understand the underlying cause of anemia. High counts can signal increased red blood cell destruction (hemolysis), while low counts might suggest conditions like aplastic anemias, kidney disease, or hypothyroidism.

The shape and size of your red blood cells can also provide crucial information. Microscopic changes in the cells, like tiny spheres or stacked-coin formations, might indicate hemolysis or multiple myeloma, respectively.

Lab tests such as Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH), haptoglobin, and bilirubin can help rule out hemolysis. An ‘Iron panel’ can also give a detailed look at your body’s iron levels.

If a secondary cause is suspected for normocytic normochromic anemia, additional tests may be done based on your symptoms or the doctor’s hunch. This could include tests for kidney function, autoimmune disorders, thyroid function, multiple myeloma, aplastic anemia or red cell aplasia.

Treatment Options for Normochromic Normocytic Anemia

The treatment for normocytic normochromic anemia largely depends on managing the condition that is causing it. Blood transfusion is a vital short-term option, particularly for those with severe anemia, where the red blood cell count is extremely low. This option is especially important for those who show symptoms of anemia, or who have related heart diseases.

In cases of anemia due to long-lasting diseases, the primary approach is to deal with the underlying health issue. While this form of anemia is generally mild, in about 20% of cases the red blood cell count may be quite low. For these severe cases, it’s necessary to screen for other potential causes of anemia, such as iron deficiency. Treatment often involves stimulating red blood cell production, blood transfusions, and supplementing iron. If patients show low or unusually normal levels of a hormone called erythropoietin, they might respond positively to injections of this hormone. Patients with very high levels of this hormone typically do not respond to such treatment. Mistaking this condition for iron deficiency can be dangerous, as excessive iron may lead to serious health issues such as liver damage, seizures, heart attack, or even unconsciousness.

If anemia results from acute blood loss, the focus will be on stopping the bleeding. Supportive measures like intravenous fluids, red blood cell transfusions, and extra oxygen can also help.

In the case of rheumatoid arthritis, a specific treatment can reduce the severity of anemia. If anemia is a result of end-stage kidney disease, the goal is to maintain a certain level of red blood cells. These patients might also need iron supplements, preferably given intravenously.

If anemia results from primary bone marrow failure, conditions like aplastic anemia may require immune system suppression therapy or bone marrow transplantation. If anemia is due to a condition called hemolytic anemia, the treatment will often depend on the specific cause. For example, if it’s caused by faulty mechanical heart valves, these might need replacing. If it’s due to medication, that drug would need to be discontinued. In some cases, the anemia may need to be managed with a surgical procedure called splenectomy.

There are conditions called Hemoglobinopathies that might require simple or exchange blood transfusions, or a medication called hydroxyurea. The condition known as DIC requires removing the source of the problem. If life-threatening bleeding occurs, treatments to slow down the breakdown of blood clots along with transfusions of blood products may be essential.

What else can Normochromic Normocytic Anemia be?

In cases of sudden blood loss from an injury, anemia may not be immediately visible in lab tests. This is due to a faster fluid shift that doesn’t give the body enough time to balance the amount of blood in circulation and therefore dilute the remaining red blood cells.

Indeed, the number of red blood cells may appear lower than they actually are due to two main factors. First, a significant dilution of the blood due to an extensive fluid refill in the case of severe dehydration. Second, the rupture of blood cells during the process of drawing blood for testing.

Anemia can come in many forms:

- Iron deficiency anemia can appear as normal in tests during its early stages.

- Other causes of anemia which may make the blood cells smaller include Thalassemia, sideroblastic anemia, and lead poisoning.

- Both B12 deficiency and folate deficiency can lead to anemia with large red blood cells.

- Liver disease often leads to anemia with large red blood cells.

- Sudden blood loss, especially due to bleeding in the digestive tract, can lead to anemia.

What to expect with Normochromic Normocytic Anemia

Normocytic normochromic anemia itself isn’t usually severe, but it can get worse over time depending on what’s causing it. If the anemia accompanies long-term health issues like bone marrow failure, autoimmune diseases or cancer, the outlook (prognosis) could be poor.

Additional health conditions like heart disease can also impact the prognosis, particularly in older people. On the brighter side, anemia caused by sudden blood loss has a positive outlook if treated early. The death rates are low for anemia caused by the destruction of red blood cells, known as hemolytic anemias.

The severity and effects of hemolytic anemia depend on what’s causing it. For example, the prognosis will vary if it’s due to conditions like sickle cell anemia or malaria. However, in general, the prognosis of normocytic normochromic anemia is most strongly influenced by the underlying disease that is causing the anemia in the first place.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Normochromic Normocytic Anemia

Normocytic anemia, a condition characterized by having an average size but a decreased number of red blood cells, is often due to issues with red cell production or a deficiency of a hormone called erythropoietin, especially in people with kidney failure. Like anemia associated with chronic infections or various long-term illnesses, the symptoms are often related to those of the underlying condition. However, in some instances, anemia may be the most noticeable symptom. The complications of normocytic anemia differ based on what the underlying disease is. Some of these complications include:

- Hypoxia, which involves a lack of sufficient oxygen and can lead to respiratory failure or organ damage

- Renal osteodystrophy, a bone disease that occurs with chronic kidney disease, associated with overactive parathyroid glands

- Cardiorenal anemia syndrome, where severe anemia results in a decrease in blood flow to the kidneys, causing further kidney damage

- Heart disease

- Multiorgan failure

- Enlarged liver (hepatomegaly) or spleen (splenomegaly)

- Jaundice, which is a yellowing of the skin and eyes

Anemia itself can also cause a range of complications, including:

- Cardiovascular compromise —a condition where the heart can’t pump enough blood

- Shock — a serious medical condition where the organs aren’t getting enough blood flow

- End-organ dysfunction — wherein one or more organs don’t work properly

- Functional limitation — a decrease in physical ability

Preventing Normochromic Normocytic Anemia

Individuals who are at a high risk for certain medical conditions should consider getting evaluated by a team of healthcare professionals. It’s essential for these patients to collaborate with their healthcare provider to manage their existing health conditions and take care of any immediate concerns such as bleeding, while also adopting healthier habits. In addition to this, patients should be given sufficient information about their specific health condition and potential consequences of normocytic normochromic anemia. This ensures that they are well-informed about the state of their health.