What is Vein Graft Stenosis?

Bypass surgery using a greater saphenous vein graft, which is a type of blood vessel taken from your own body, is a proven treatment for diseases affecting the arteries in the lower limbs. This treatment can help to manage a range of conditions with different causes, such as chronic limb-threatening lack of blood supply, pain during activity due to narrowed arteries, dilation of an artery in the limbs, and significant limb injury. Generally, results from this surgery are favorable, with successful preservation of the limb and long-lasting performance of the grafts. However, these grafts can sometimes fail due to narrowings known as ‘stenoses’ which limit the effectiveness of the treatment. Spotting these stenoses by monitoring symptoms and using ultrasound scans, followed by appropriate treatment, can help to prevent a complete blockage of these grafts.

Maintaining the performance, or ‘patency,’ of these grafts in the long term can be a challenge because they can develop narrowings from fat and cholesterol deposits, known as atherosclerosis, more quickly than arteries. Thus, preventing these narrowings is a key priority. This involves careful control of blood pressure, blood sugars, cholesterol levels, body weight, and stopping smoking. It is generally advised that all patients with these grafts take daily aspirin and cholesterol-lowering drugs known as statins. Additional blood thinners or antiplatelet drugs may be required, depending on the specifics of certain surgeries performed and individual patient circumstances.

The most common symptom of these narrowings in coronary artery bypass surgery is chest pain known as angina. In the case of peripheral arteries, symptoms can include pain at rest, non-healing wounds, and pain during activity or ‘claudication’. If it becomes necessary to restore blood flow, treatment options to improve blood supply to the affected vessel include minimally invasive, or ‘endovascular’ therapies, or another bypass surgery. Minimally invasive treatments of the graft itself may be tried first to improve performance. More invasive surgery is held in reserve for disease affecting multiple blood vessels or patients for whom less invasive treatments are not possible. This explanation covers these narrowings in patients following coronary artery bypass surgery, and peripheral artery bypass surgery using the greater saphenous vein, which is the most commonly used type of vein for these procedures.

What Causes Vein Graft Stenosis?

When a physician uses a vein from the leg (the saphenous vein) in a graft surgery, like a bypass to improve blood flow, the success of the graft can be assessed at different times: early (0 to 30 days), short-term (30 days to 2 years), and long-term (more than 2 years).

Sometimes the graft can fail early, within the first month. This is often due to technical reasons like the positioning of the graft, the graft getting twisted or bent, or poor blood flow at the end of the graft. This early failure accounts for around 10% of all graft failures.

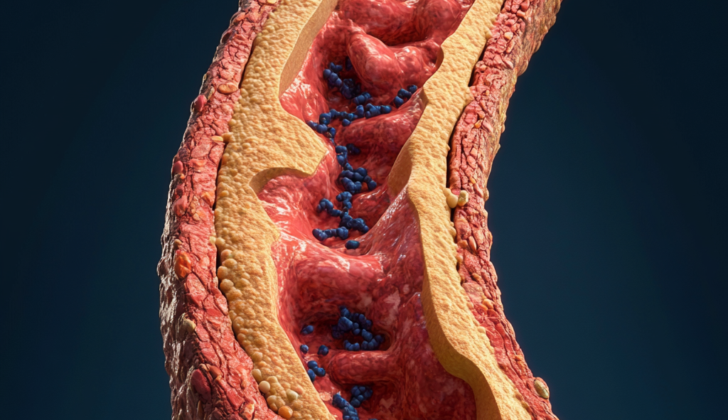

The reasons why a graft can fail in the short term are less clear. Several factors may be involved, including changes in nearby muscle cells, growth of smooth muscle cells caused by certain growth factors, a decrease in the release of nitric oxide (which helps regulate blood vessel function), a decrease in the relaxing of the endothelium (the inner lining of blood vessels), and thickening of the inner layer of the vein wall.

Late failures of the graft, happening after two years, occur similarly to how heart disease forms. It involves plaque building up next to areas where fat has been deposited and a thickening of the innermost layer of the artery (a process named intimal hyperplasia).

Risk Factors and Frequency for Vein Graft Stenosis

Annualy in the United States, over 300,000 patients undergo a surgery called CABG (coronary artery bypass graft) where the saphenous vein is often used as a bypass for the diseased artery. This process has a significant impact on the healthcare system. About 10% of the vein grafts used in this procedure may become blocked before a patient even leaves the hospital. In the year following surgery, blockage can happen to 15% to 30% of grafts. After the first year, the blockage rate is roughly 2% each year, but this percentage doubles between the sixth and tenth years post-surgery.

Around 15% of people over 70 develop a condition called peripheral artery disease. Half of those affected will show symptoms, and about 1% of symptomatic patients develop a severe version of this disease, potentially needing a different type of bypass graft (PABG). The failure rate of this bypass method remains high, especially for grafts in the lower extremities, with about 20% failing in the first year and half of these failing by the fifth year.

Signs and Symptoms of Vein Graft Stenosis

Patients who have VGS (vein graft syndrome) after CABG (Coronary Artery Bypass Graft surgery), often feel symptoms commonly identified with angina (chest pain). As the vein graft stops functioning, these people may experience sensations of chest pain and pressure in the area of their breastbone, even while resting. Other signs that indicate the lack of proper blood supply to the heart, or ischemia, can include shortness of breath, heart palpitations, physical weakness, sweating, nausea, and discomfort in the upper belly.

Upon a physical check-up, doctors may identify symptoms of acute coronary syndrome in these patients. Such symptoms could include sweating, skin paleness, high pressure in the neck veins, crackling sounds in lungs, abnormal heart sounds, and swelling in both lower legs.

Patients with VGS after PABG (Peripheral Artery Bypass Graft) commonly experience pain at rest, limping due to muscle pain, and persistent sores that don’t heal. A physical examination may reveal tell-tale signs like thinning skin, colder leg temperatures, hair loss, weak or non-existent pulses in the limbs, chronic sores that don’t heal, loss of sensation, reduced muscle function, and abnormal nerve reflexes.

- Chest pain or pressure

- Shortness of breath

- Heart palpitations

- Physical weakness

- Sweating

- Nausea

- Discomfort in the upper belly

- Sweating, skin paleness

- High pressure in the neck veins

- Crackling sounds in lungs

- Abnormal heart sounds

- Swelling in both lower legs

- Pain at rest, limping due to muscle pain

- Persistent unhealing sores

- Thinning skin, colder leg temperatures

- Hair loss

- Weak or non-existent pulses in the limbs

- Loss of sensation, reduced muscle function

- Abnormal nerve reflexes

Testing for Vein Graft Stenosis

If your doctor believes you may be experiencing a blocked vein graft, which can lead to a lack of blood flow to the heart (a condition known as cardiac ischemia), they’ll likely perform a few tests. One essential test is a 12-lead electrocardiogram, which checks the electrical activity of your heart and can possibly spot any abnormalities. Your doctor will likely compare the readings to your previous tests to look for any new irregularities like problematic heart rhythms (bundle branch blocks), changes in the ST segment, or T wave abnormalities.

They may also run some laboratory tests, which could include checking for certain heart-related chemicals in your blood, such as cardiac troponin, creatine kinase-MB, and B-type natriuretic peptide. Elevated levels of these chemicals can indicate heart damage.

Although a chest X-ray isn’t likely to reveal a blocked vein graft in and of itself, it can be useful if your doctor suspects new-onset congestive heart failure (a condition where your heart doesn’t pump blood as well as it should) caused by lack of blood flow. The X-ray may show an enlarged heart (cardiomegaly) and fluid build-up in the lungs (pulmonary congestion). In a severe condition, your chest X-ray may show signs of excess fluid in the lung structure (like Kerley B lines) or fluid in the lung’s air sacs, which is known as alveolar edema.

Lastly, an echocardiogram (an ultrasound of the heart) could be used to evaluate any significant drop in your heart’s pumping capability, assess for a new irregular movement of the heart walls or check for leaking heart valves likely caused by malfunctioning papillary muscles (the muscles that help the heart’s valves work).

If you’re showing signs and symptoms of Vein Graft Stenosis (VGS) after bypass surgery, your doctor will first check for pulses in the leg using a device called a handheld Doppler. To better understand blood flow in your leg, they might take blood pressure readings from your arm and ankle to calculate a ratio called the ankle-brachial index. A normal ratio (>0.9 to 1.1) indicates healthy blood flow in your leg’s arteries. Lower numbers can indicate problems with blood flow.

If the ratio is low, further tests will likely be required. Imaging tests, such as Doppler ultrasound, CT scan, or MRI, can show the specific location and severity of the blockage in your leg’s artery. In some cases, a more direct but invasive test (angiography) may be used, which involves inserting a thin tube called a catheter into the artery. However, this procedure carries a higher risk compared to less invasive imaging methods.

Treatment Options for Vein Graft Stenosis

The best way to manage Vein Graft Stenosis (VGS), a condition where the blood vessels become narrow due to plaque buildup, is to prevent it from happening in the first place. During the first month after a vein graft, VGS can be prevented with careful surgical practices and appropriate drugs to prevent blood clots. Proper vein graft placement during surgery and avoiding any bends or twists in the graft is crucial. A robust target blood vessel, one that has good blood flow downstream, should be preferred.

For both short-term (one to eighteen months) and long-term (more than eighteen months) prevention of VGS, management practices involve slowing and preventing the growth of a thick layer of cells (intimal hyperplasia) and the build-up of fat, cholesterol, and other substances in the blood vessel walls (atherosclerosis). Multiple factors that contribute to VGS are similar to those that cause arterial atherosclerosis. A healthy diet, regular exercise, keeping blood glucose and blood pressure levels under control, management of high blood lipid levels (dyslipidemia), and quitting smoking are recommended for all patients with artery diseases. The usage of low-dose aspirin after surgery has shown a drop in VGS occurrence.

A trial showed that using ticagrelor, a blood-thinning drug, along with aspirin, improved vein graft survival rates without increasing significant bleeding risks for those who have undergone coronary artery bypass surgeries. Yet, for bypass surgeries for peripheral arterial disease (in the extremities), the addition of ticagrelor didn’t significantly affect VGS. Therefore, patients should receive a combination of blood-thinning drugs following a coronary artery bypass, but only aspirin following a peripheral artery bypass unless there is another reason to do so. Post-surgical treatments to prevent clotting didn’t prove to prevent VGS. Statins, drugs used to lower blood cholesterol levels, along with aggressive control of dyslipidemia, have shown an improvement in patient conditions following bypass surgeries, including slowing down VGS. Early detection of VGS during routine check-ups using Doppler Ultrasonography, an imaging technique that uses sound waves, can help in preventing complete graft failure.

If prevention is not successful and VGS worsens, there are several treatment options. These include opening up the original blocked vessel, opening up the blocked vein graft, or redoing the surgery. If possible, the first step should be to open up the original blocked vessel. If that’s not possible, then attempting to open up the blocked vein graft would be the next step. Surgery should be saved for cases that cannot be resolved with these less invasive methods first. There’s currently no hard evidence favoring one type of intervention over the others for vein grafts following infrainguinal bypass, a procedure that treats blockages in the blood vessels below the groin.

When a procedure to open up the blocked vessel is done, the decision must be made whether to use a bare-metal stent or a drug-eluting stent. Studies comparing the two types of stents have had varied results, and a recent review of multiple studies failed to show a difference between the two types of stents in regard to patient outcomes at 42 months follow up. Therefore, the choice between a bare-metal stent and a drug-eluting stent depends upon individual patient factors, physician preference, and what’s available at the medical facility. Regardless of what type of stent is used, it’s essential to avoid breaking off and sending downstream any fragments of the plaque during the procedure, making the use of an embolic protection device necessary in all suitable cases.

What else can Vein Graft Stenosis be?

After heart surgery (CABG) with a vein graft, doctors look for signs of several complications:

- Myocardial ischemia of a native artery (restricted blood supply to the heart)

- Cardiac arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat)

- Pulmonary embolism (blood clot in the lungs)

- Aortic dissection (tear in the aorta)

- Musculoskeletal pain (pain in the muscles or bones)

Similarly, after peripheral artery bypass grafting surgery (PABG) with a vein graft, doctors look out for:

- Critical limb ischemia of a native artery (sudden decrease of blood flow to a limb)

- Arterial aneurysm (bulging, weak area in an artery wall)

- Arterial dissection (a tear in the artery)

- Thromboembolism (blood clot travelling through the bloodstream)

- Neurological pain (pain resulting from damage to the nervous system)

- Musculoskeletal pain (pain in the muscles or bones)

What to expect with Vein Graft Stenosis

Revascularization, a procedure to restore blood flow through blocked veins, is less successful for vein grafts compared to arterial blockages when considering overall death rates, how long one can live without experiencing a serious event, and the total amount of diseased vein grafts at 5 years. In fact, people who have to go through a redo of their original coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG, a type of heart surgery) have nearly a 10% chance of dying during or after the procedure, which is more than three times higher than the roughly 3% death rate for the original surgery.

Poor heart function, needing insulin for diabetes, having the second surgery within a year of the first one, and kidney disease can all increase the risk of death from the repeated CABG procedure. People who are critically ill with poor blood flow to their limbs, a common reason for needing Popliteal Artery Bypass grafting (PABG, a type of leg surgery), don’t have a good prognosis. At 1 year after diagnosis, approximately 45% of people survive with both limbs, 30% have had an amputation, and 25% have died.

And at 5 years after diagnosis, about 60% of people with this condition die. The prognosis is even worse for people with kidney disease, those who continue to smoke, and those with diabetes. Vein grafts in the legs are hard to keep open. However, grafts that were regularly checked and treated for narrowing, as identified on scheduled imaging tests, stayed open 82% to 93% of the time at 5 years. This is considerably higher than the 30% to 50% rate for grafts that were not regularly checked.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Vein Graft Stenosis

Sometimes, after a great saphenous (a large vein of the leg) coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), a heart surgery, or peripheral artery bypass grafting (PABG), a limb surgery, you might experience some health issues. These complications can range from minor such as bleeding and infection, to serious ones like heart failure, kidney failure, or shock. You might also experience graft failure, which can be either immediate or delayed. In certain cases, there might be blood clots that block blood flow (known as distal thromboembolism), inflammation of the heart’s outer layer (pericarditis), or even fatal outcomes.

Complications following PABG could also include compartment syndrome, a painful and dangerous condition caused by pressure buildup from internal bleeding or swelling of tissues. Critical limb ischemia, a severe obstruction of the arteries, could occur too which reduces blood flow to the extremities (hands, feet and legs) and causes severe pain. Imbalances of minerals in the body (or electrolyte abnormalities), bulging or weakened areas in the walls of an artery (arterial aneurysm), tears in the artery walls (arterial dissection), bleeding and infection are some other possible complications.

Potential complications:

- Bleeding

- Immediate or delayed graft failure

- Infection

- Heart failure

- Myocardial infarction (heart attack)

- Distal thromboembolism (blood clot)

- Pericarditis (heart inflammation)

- Renal failure (kidney failure)

- Shock

- Death

- Compartment syndrome

- Critical limb ischemia

- Electrolyte abnormalities

- Arterial aneurysm

- Arterial dissection

Preventing Vein Graft Stenosis

The best way to handle Vein Graft Stenosis (VGS), a condition where your vein grafts, or blood vessel transplants, narrow, is to prevent it. You can do this by maintaining a healthy weight, taking your medications as recommended, exercising, and quitting smoking. These steps can help you avoid needing another procedure or surgery.

If you’re diagnosed with VGS affecting the blood vessels supplying your heart, there are two main treatment options. One is to have further open heart surgery, which is a major procedure and carries significant risks. The other is called PCI (Percutaneous Coronary Intervention). In this procedure, doctors use a tube inserted through an artery in your arm or leg to place a device called a stent into the narrowed blood vessels to improve blood flow. To prevent any blockages from breaking off and causing other problems during the stent placement, strict precautions are taken.

If you have VGS in the peripheral arterial system – the blood vessels outside of your heart – the approach is similar. Preferred methods include endovascular reperfusion, a procedure using a stent or balloon to open the blocked vessel to restore blood flow. If these methods aren’t successful or aren’t possible, a traditional surgery may be needed.

Unfortunately, some patients cannot have these procedures. In these cases, these patients receive medications that thin the blood to help restore blood flow.