What is Inferior Shoulder Dislocations?

The shoulder joint, also known as the glenohumeral joint, is the joint most often dislocated in the human body. It’s responsible for around half of all major dislocations that are treated in emergency departments. It’s quite common for the shoulder to dislocate towards the front and this scenario is frequently seen by doctors. However, it’s rather rare for the shoulder to dislocate downwards – it happens in only about 1 in every 200 shoulder dislocations. This kind of dislocation is very noticeable, and doctors can usually identify it just by looking at the patient from the entrance of the examination room.

What Causes Inferior Shoulder Dislocations?

This dislocation type is commonly known as “luxatio erecta”, a Latin phrase meaning “erect dislocation”. This term comes from the unique way the arm is typically positioned during this injury – stretched out and held above the head.

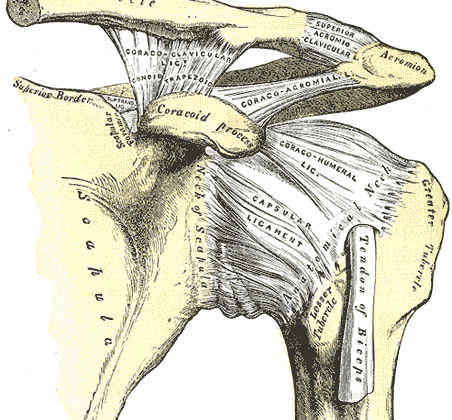

Many cases of this dislocation occur due to traumatic accidents, for example, falling off a motorbike. In these incidents, the top part of the upper arm bone (the humerus neck) is thrust against a part of the shoulder blade (the acromion). This often results in damage to the underside of the shoulder capsule. It’s also common for this type of dislocation to come with soft tissue injury or fractures.

Moreover, injury to the nerves and blood vessels in the shoulder, including damage to the axillary nerve, can frequently happen when there is inferior shoulder dislocation.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Inferior Shoulder Dislocations

Luxatio erecta, a type of shoulder dislocation, is quite rare, making up less than one percent of all shoulder dislocations. However, when it does occur, it is about ten times more common in men than in women.

Signs and Symptoms of Inferior Shoulder Dislocations

If a person has experienced a shoulder dislocation where the bone slips downward, they’ll usually experience significant pain. The cause of the dislocation can help identify other potential injuries. For example, if the shoulder was dislocated during a high impact event, other trauma-related injuries may be present. If it happened due to a simple fall with the arm extended outward, the lower part of the joint might also be injured. Commonly, an MRI scan taken after this kind of injury will show damage to the rotator cuff, the ring of muscle and tissue that keeps the shoulder bone in its socket, injuries to the glenoid labrum, or the rubbery tissue at the end of the shoulder blade, bone bruises, and fractures where the upper arm bone has been pushed into itself.

When looking at the injured arm, it will usually appear raised up above the head with the elbow bent at a right angle. It’s important to check for injuries to the nerves and blood vessels in the arm, particularly the axillary nerve along with the radial and ulnar nerves – since these are often affected in downward shoulder dislocations. The patient will likely struggle to move their arm downward without experiencing a lot of pain. It might also be possible to feel the dislocated bone in the armpit or on the side of the chest. It should be noted that if the dislocation happened during a high-impact event, there might be other serious injuries, such as to the chest or abdomen.

Testing for Inferior Shoulder Dislocations

If a doctor suspects a shoulder issue, they will commonly use standard shoulder x-rays for the diagnosis. These images, taken before and after the procedure, will include a front-to-back (known as anterior-posterior or AP) view, as well as a scapular ‘Y’ view. While another view, known as the axillary view, can offer some useful insights for certain shoulder problems, it won’t clearly show the relationship between the top part of your arm bone (the humeral head) and the socket (the glenoid). Any overlap between these parts would be readily visible in this view.

In certain cases, the shoulder might dislocate downwards rather than to the front or back. This so-called ‘inferior dislocation’ can also come with other broken bones, something a physical exam on its own might not necessarily detect. In such situations, x-rays would typically show the top part of your arm bone sitting below the rounded hollow in your shoulder blade (the glenoid fossa). Specifically, on the scapular ‘Y’ view, the head of the arm bone can be seen beneath where it normally would be, right at the centre of the ‘Y’ shape made by the shoulder blade.

If there are concerns about any damage to blood vessels or nerves, angiography or Doppler studies might be performed. An electromyogram (EMG) could also be used to check for any nerve injuries. To see the full extent of any damage to the body’s soft tissue, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is often used.

Treatment Options for Inferior Shoulder Dislocations

When a shoulder dislocation happens, doctors use a procedure called sedation to relax the muscles, making it easier to put the shoulder back into place using a method called traction-counter-traction. In some unusual scenarios, the head of the arm bone (humerus) gets stuck in a tear in the surrounding tissue (known as a “buttonhole” deformity), requiring open surgery to fix.

To treat a lower shoulder dislocation, doctors stretch the arm out and gently pull it upward along the length of the arm bone. Sometimes, a second doctor might press gently on the head of the arm bone to help guide it back into place. Counter-traction can also be applied, which involves pulling in the opposite direction using a sheet draped over the shoulder.

After the shoulder has been put back into place, the doctor will move the arm back towards the body while turning the lower arm to a palm-upward position. Another approach is using a two-step method. In this technique, the lower dislocation is first shifted to an outward misalignment, before being repositioned correctly. Here, one hand is placed on the dislocated bone while the other hand is kept on the elbow’s inner end. The arm bone is then brought close to the body and using known techniques, adjusted into its proper spot. This two-step process sometimes proves more effective as it requires less force and can be done with local anesthesia. After successful adjustment, you may feel or hear a “clunk” sound, signaling that the bone has returned to its normal position, and you should be able to move your arm freely.

After being set back into position, your arm will be rested in a shoulder immobilizer to prevent another dislocation as the muscles and tissues around may still be damaged and loose. Another thorough checkup should be performed after this procedure to ensure no injuries occurred during the operation. Usually, an X-ray is done at this point to confirm the successful adjustment and to double-check for any possible injuries. In rare instances where the shoulder couldn’t be put back into place using these techniques (as in the case of the “buttonhole deformity”), a surgical procedure is required. Surgery may also be necessary if the dislocation can’t be managed with usual techniques, if the dislocation is exposed, or if there’s a blood vessel injury.

rotator cuff syndrome and related rotator cuff injuries.

What else can Inferior Shoulder Dislocations be?

- Broken collarbone

- Stiff shoulder (also known as “Frozen Shoulder”)

- Broken upper arm bone

- Tear in the shoulder muscles (known as the “rotator cuff”)

What to expect with Inferior Shoulder Dislocations

Most people who experience a shoulder dislocation are young, and many of them may face another dislocation down the line. Often, this injury involves a tear in the rotator cuff and usually, mild injury or trauma cause many of these recurrent dislocations.

Patients may experience pain severe enough to limit their return to sports, or they may need to limit their use of the injured arm and shoulder for about 2-6 weeks. The re-injury rates among athletes are quite variable, with up to 30-90% facing another dislocation in the future.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Inferior Shoulder Dislocations

Common Complications:

- Bone breakage

- Damage to nerves or blood vessels

- Stiff shoulder that is hard to move

- Injury to soft tissues like muscles or ligaments