What is Radial Nerve Entrapment?

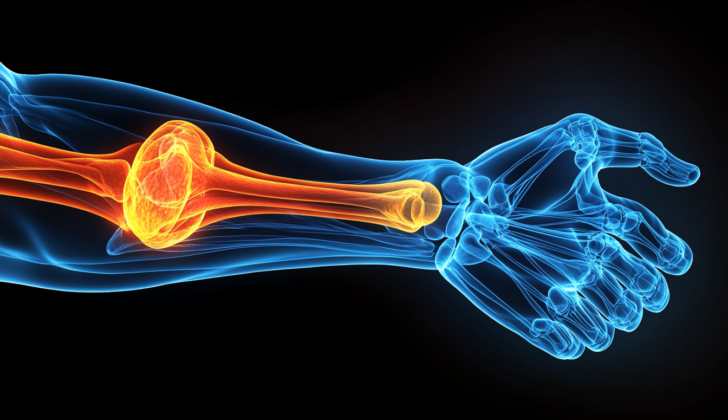

Radial nerve entrapment is a condition that often goes unnoticed, although it’s not very common. It happens when the radial nerve, which runs down the arm, is compressed or trapped at different points, most frequently near the upper part of the forearm. This pressure often impacts a subsection of the radial nerve called the posterior interosseous nerve.

The radial nerve comes from the sections C5 to C8 of the spinal cord and is responsible for moving the forearm, wrist, fingers, and thumb. A part of it, known as the superficial radial nerve, plays a role in feeling sensations in the back part of the forearm. If the radial nerve is trapped in any location, it could result in symptoms like pain, numbness, muscle weakness, difficulty moving the affected area, or a combination of these conditions.

What Causes Radial Nerve Entrapment?

Radial nerve entrapment, a condition where the radial nerve gets pinched or compressed, is usually caused by overusing the arm. However, it can also be due to other reasons like direct injury, fractures, cuts, using compressive devices, or changes after surgery.

The radial nerve splits into two parts when it reaches the juncture of the radius and the capitellum (or radiocapitellar joint in medical terms) – these are called the superficial radial and the posterior interosseous nerves. The posterior interosseous nerve goes along the side of the radius bone before it goes through the supinator muscle, which is one of the usual places where it can get entrapped.

This nerve then divides into four more branches that can get compressed at four different places. These are: the fibrous bands around the radial head (top of the radius bone), the recurrent radial vessels, the arcade of Frohse (a fibrous band in your forearm), and/or the tendinous margin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis, a muscle in the forearm.

Activities and exercises that can lead to this condition are often involved repeating pronation (turning the palm of your hand down) and supination (turning the palm up) of your wrist and forearm. These types of actions tend to occur in the places we discussed earlier.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Radial Nerve Entrapment

It’s quite rare to have a condition called radial nerve entrapment. It’s often overlooked or not properly recognized. According to estimates, the risk of experiencing the compression of the posterior interosseous nerve, a specific type of this condition, is around 0.03% per year. The risk is even lower for the superficial radial nerve compression, at about 0.003% per year.

Signs and Symptoms of Radial Nerve Entrapment

When it comes to diagnosing nerve entrapment, the signs and symptoms can vary greatly because the nerve can be trapped in several different places. That being said, symptoms tend to appear very slowly. Many times, people have been experiencing symptoms for years by the time they are finally diagnosed.

A variety of symptoms might hint at a nerve entrapment problem. These include pain, changes in sensation or movement, a prickling or tingling feeling, and/or even paralysis. Typically, these symptoms are only felt on the top side of the lower arm and hand (the dorsoradial aspect). Decreased sensation in this area can also point to nerve entrapment.

- Pain

- Changes in sensation or movement

- Prickling or tingling feelings

- Paralysis

- Decreased sensation over the top side of the lower forearm or hand

A medical history or physical exam can help confirm these symptoms. Two tests might be used to support the diagnosis. A positive Tinel sign, which is a tingling sensation when a healthcare provider taps over a nerve, can be suggestive of this process. When flexing the wrist, bending it towards the pinky finger, or flipping the hand over strains the nerve, it can often bring about or worsen symptoms. When asked to resist the extension of the middle finger while straightening the elbow, patients with nerve entrapment often struggle. This is a sign frequently used to help diagnose this condition, but it is also often present in cases of radial nerve entrapment.

Testing for Radial Nerve Entrapment

If your doctor thinks nerve entrapment might be causing your symptoms, they’ll want to do some tests to see what’s happening and make sure they’re not missing anything. They might start with X-rays to look for things like fractures, healing bones, or tumors that could be causing the problem.

Another tool they can use is an ultrasound. This uses sound waves to create an image of what’s going on inside your body. With an ultrasound, they can often see if a nerve has been hurt. Some things they might be looking for include swelling in the nerve, changes in how the nerve looks, breaks in the nerve, growths on the nerve, or partial cutting of the nerve. All of these could indicate a problem that might help your doctor figure out what’s happening.

If the X-rays and ultrasound don’t give them enough information, they might do an MRI. This is another kind of imaging test that can help find smaller problems the other tests might miss, such as tiny tumors, growths, blood vessel problems, or inflammation. An MRI can sometimes also detect changes in a nerve when it’s being squeezed or entrapped.

Sometimes your doctor might decide to do a diagnostic nerve block. This is a kind of test where your doctor injects medication near a nerve to see if it changes your symptoms. This can help them figure out exactly where the problem is and how it’s affecting you.

Finally, they might consider EMG/nerve conduction studies, but these tests aren’t always reliable. Your doctor will only consider them if they’re thinking about doing surgery. Normally, you don’t have to do any standard lab tests to figure out if you have nerve entrapment.

Treatment Options for Radial Nerve Entrapment

First and second degree nerve injuries usually heal over time. Most people improve after a few months. Doctors recommend regular check-ups and specific tests known as EMG/NCS to track your nerve health over time. Many patients find relief with non-invasive treatments. This can include removing tight or constrictive items you regularly wear or changing some of your daily activities that may be causing stress to the nerves. Frequently, these actions are things like repeated twisting, bending, or unusual movements of the wrist.

In addition, your doctor may suggest nerve glide exercises. These are specially designed movements performed as part of your occupational or physical therapy. They go hand-in-hand with rest and changes to your activities. If these changes do not relieve your symptoms, your doctor may suggest wearing a splint to hold your wrist steady.

If your doctor can spot a specific area of damage using ultrasound and it looks like it might be caused by compression, a procedure called ultrasound-guided hydro-dissection may be an option. This is a minimally invasive procedure that can help relieve pressure on the nerve.

For pain relief, oral or topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) might be recommended. In some cases, a shot of both a corticosteroid and a local anesthetic may be given at the point where you feel the greatest pain. The corticosteroid can help reduce any inflammation that might be contributing to your symptoms. If the injury isn’t severe, but there is still no sign of recovery after some time, surgery may be considered. This is usually the last resort if months of non-surgical treatment haven’t helped.

Third-degree nerve injuries are more serious. These injuries, known as Neurotmesis, often require immediate surgery to repair the nerve, whether the damage is partial or complete. In scenarios where the nerve damage has resulted in a retraction, creating a gap in the nerve, nerve grafting methods are used. This usually happens some time after the initial injury. If there are any long-lasting defects or “injury gaps” bigger than 2.5 cm, nerve grafting techniques are the recommended treatment. Options for the nerve graft include using your own sural or saphenous nerves. Studies have shown no difference in recovery or outcome when comparing the use of your own nerve (autograft) with using a nerve from a donor (allograft) or nerve conduits.

What else can Radial Nerve Entrapment be?

- Median nerve damage

- Multifocal motor nerve damage

- Radial nerve damage

- Ulnar nerve damage

What to expect with Radial Nerve Entrapment

If your radial nerve, which is a major nerve in your arm, becomes trapped and only lightly damaged (a condition known as neurapraxia), you should recover quickly, usually within 2 to 8 weeks. But if the injury is more severe (a condition known as axonotmesis), recovery will take longer. The length of your recovery depends on how far the healing nerve cells must grow to re-establish connections with the muscles they control. This process usually occurs at a rate of about 1mm each day.

Your recovery after surgery depends on how severely your nerve was damaged before the operation. If you had mild damage (neurapraxia) and got early treatment, you have an 80 to 90% chance of returning to normal. However, even with early treatment, people with severe damage (axonotmesis) are less likely to fully recover.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Radial Nerve Entrapment

The majority of the problems that happen are due to the surgery, and they include:

- Stretching of the nerve

- Cutting of the nerve

- Not fully releasing the nerve

- Shrinking of the muscle

Preventing Radial Nerve Entrapment

The reason for a patient’s condition, and whether they’ve had surgery, will affect how they need to adjust their activities and engage in strength-building exercises for recovery. If surgery was necessary, managing the recovery process should involve making sure the patient understands what to expect, given how severe their nerve damage is. They will also have to work with a physical therapist (PT) and possibly an occupational therapist (OT) to help them regain strength and function.

No matter the situation, it’s crucial that patients stick to the plan provided by the medical team, whether it’s an exercise routine or daily living modifications. This helps prevent further harm and promotes healing. It’s also important that any activities that may cause harm or exacerbate the condition should be stopped permanently.