What is Syringomyelia?

Syringomyelia is a condition where abnormal circulation of a fluid called cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) results in the creation of fluid-filled spaces known as syrinxes in the spinal cord or its central canal. These syrinxes are usually linked with Chiari malformation type 1 (CM-1), a condition where brain tissue extends into the spinal canal. Syringomyelia can also be caused by factors such as spinal cord tumors, injuries, or an infection-induced condition called adhesive arachnoiditis.

Mostly, people with syringomyelia experience sensory symptoms like decreased sensitivity to pain and temperature, but in many cases, it’s detected unexpectedly during routine check-ups. With the frequent use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a type of scan used to look at the body’s internal structures, for evaluating back and neck pain, syringomyelia is being discovered more commonly.

The progression of syringomyelia in patients can vary widely, with periods of stability and worsening of the condition. The exact progress of the disease isn’t fully understood, but it usually gets worse over months to years after an initial fast deterioration, followed by a slower decline. Activities like sudden head movements or long bouts of coughing can cause an abrupt onset of symptoms in someone previously without symptoms, possibly due to an increase in the abnormal downward displacement of the brain into the spinal canal. It’s important to note that syringomyelia is responsible for up to 5% of cases of paraplegia, a condition that can result in the loss of feeling or movement in the lower part of the body.

What Causes Syringomyelia?

Syringomyelia happens when there’s a problem with the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), a clear liquid that protects your brain and spine. This problem usually results from a blockage in the surrounding space, known as the spinal subarachnoid space.

Syringomyelia is classified into three types:

1. Communicating: This type involves an enlarged pathway in the spinal cord that’s connected with the fourth ventricle (a space in the brain that holds CSF) accompanied by accumulation of fluid in the brain (hydrocephalus). The inside of the cavity created by this condition is lined with ependymal cells, a type of brain cell.

2. Non-communicating (isolated): This type is characterized by an enlarged pathway in the spinal cord caused by a change in CSF flow within the spinal subarachnoid space. It’s caused by conditions such as Chiari malformation type 1 (CM-1), basilar impression (a structural defect at the base of the skull), or inflammation of a protective layer around the brain and spinal cord called arachnoiditis. The affected areas can extend into the back and side areas of the spinal cord.

3. Extracanalicular: This type is often seen in an area of the spinal cord that’s vulnerable to injury or stroke and is usually associated with a condition called myelomalacia (softening of the spinal cord). The cavities created by this condition are lined with glial or fibroglial tissue, types of nervous system cells.

Furthermore, Non-communicating syringomyelia is divided into four sub-types as follows:

1. Type I: Happens due to a blockage at the foramen magnum (large hole at the base of the skull) causing an enlargement of the central spinal canal due to conditions such as CM-1, basilar invagination (a deformity where the skull pushes into the brain), and other conditions.

2. Type II: Happens with no blockage at the foramen magnum and is often considered unexplained or idiopathic.

3. Type III: Results from problems directly affecting the spinal cord, such as tumors, traumatic injury to the spinal cord (myelopathy), inflammation of the protective layer around the brain and spinal cord (spinal arachnoiditis), inflammation of the thick outermost layer of the meninges surrounding the brain and spinal cord (pachymeningitis), and myelomalacia (softening of the spinal cord).

4. Type IV: Pure hydromyelia or accumulation of fluid inside the spinal cord.

The causes of Syringomyelia can vary, including:

1. Cranial-cervical anomalies like CM-1 and basilar impression. CM-1 is actually the most common cause with 23% to 80% of CM-1 patients developing syringomyelia according to literature.

2. Other causes may include tumors, trauma leading to the formation of a thin membrane across a channel or cavity (dorsal arachnoidal webs), arachnoiditis, meningitis, scarring post surgery, and conditions where the spinal cord has not formed properly (dysraphism).

There are several factors that can obstruct the CSF flow including:

1. Lymphoid tissue at the base of your skull and covering the foramen of Magendie, scarring on the dura mater (tough covering of the brain and spinal cord), thickened arachnoid layer, a branch of the cerebellar artery, a cyst in the cisterna magna (a wide space in the brain that holds CSF).

2. Other factors like tonsillar gliosis (scarring of the tonsils) and tonsillar hypertrophy (enlarged tonsils) can also obstruct the CSF flow causing a disturbance.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Syringomyelia

CM-1, or Chiari Malformation type 1, is a rare condition affecting between 3 and 8 out of every 100,000 individuals. A significant number of people with CM-1 (about 65%) also have a condition called syringomyelia. There are varying statistics about how common syringomyelia is, but it could affect up to 8.4 individuals out of every 100,000. In Italy, a study showed the prevalence of the disease is 4.84 per 100,000, with around 0.82 new cases per 100,000 each year.

Among white people, the estimated prevalence is 5.4 per 100,000. However, the rate is lower in Japan, at 1.94 per 100,000. It’s important to know that not everyone with syringomyelia will experience symptoms; about 22.7% of people with the condition do not have any symptoms. It tends to be most commonly diagnosed in younger and middle-aged individuals, with peak ages being 8 for children and 41 for adults.

Thanks to advanced imaging techniques, we’re now able to detect these conditions more often, even in people who don’t show symptoms.

- CM-1 affects 3 to 8 per 100,000 individuals

- About 65% of people with CM-1 also have syringomyelia

- Prevalence of syringomyelia ranges from 8.4 per 100,000 to 0.9 per 10,000

- In Italy, the prevalence of syringomyelia is 4.84 per 100,000 with 0.82 new cases per 100,000 per year

- Among Caucasians, the prevalence is reported as 5.4 per 100,000

- In Japan, the prevalence of syringomyelia is 1.94 per 100,000

- About 22.7% of patients with syringomyelia have no symptoms

- Peak ages of diagnosis for CM-1 are 8 for pediatric cases and 41 for adult cases

Signs and Symptoms of Syringomyelia

Syringomyelia is a condition frequently linked with another disorder known as CM-1. Here’s a breakdown of the important signs and symptoms associated with it:

- Tussive headaches: These headaches occur in the hind part of the skull, instantly after a cough. They often feel heavy, crushing, and pressure-like in nature. They can be triggered by physical exertion, a change in posture, and other activities that increase pressure.

- Problems with the throat such as a rough voice, difficulty in swallowing, and abnormal coughing.

- Visual disturbances: Symptoms here include pressure behind the eyes, flashing lights, blurred vision, light sensitivity (photophobia), and double vision (diplopia).

- Oto-neurological symptoms: These are issues like dizziness, tinnitus (a ringing sound in the ear), a feeling of pressure in the ears, decreased hearing, and imbalance in visual perception.

- Cerebellar disturbances: These include involuntary trembling, inaccurate movements, troubles with balance, and gait difficulties.

- Sudden temporary loss of consciousness (syncope).

- Sleep disturbances: These incorporate problems like snoring, sleep apnea, and irregular heartbeats.

Conditions resulting from the syrinx, another name for the hollow part of the spinal cord affected by syringomyelia, can include the following:

- Paresthesia/hyperesthesia, which is an abnormal sensation, is a common symptom.

- Muscle weakness and loss of detailed motor function may lead to wasting of muscles in the hands.

- Increased muscle tone (spasticity) in legs can occur due to damage to nerve tracts in the spine.

- Progressive curvature of the spine (scoliosis) may occur.

- Horner syndrome, which can be seen in syringes affecting the neck or upper part of the chest.

- Poorly located, non-radicular, segmental nerve pain.

Patients with syringomyelia often describe various symptoms including pain, muscle weakness in the hands and arms, temperature insensitivity in the upper body, stiffness in the legs, and progressive curvature of the spine. Symptoms may worsen over time but can also occur rapidly and then decelerate. If CM-1 is also present, patients might experience headaches at the base of the skull, neck pain, and sleep disturbances. Though treatment can often improve stiffness, other neurological functions might deteriorate. Not all individuals with syringomyelia present the same symptoms, though sensory loss is often an identifier. Bladder dysfunction might also occur, while bowel problems are rare until the late stages of the disorder.

Testing for Syringomyelia

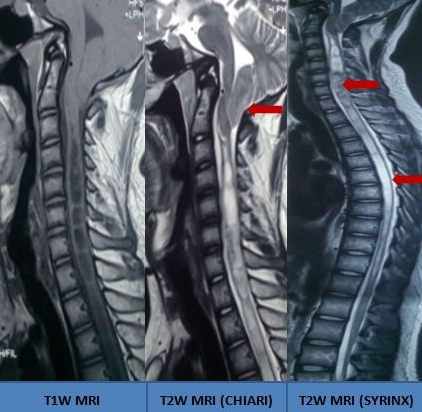

If you have been diagnosed or suspected of having syringomyelia, your doctor will most likely recommend a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan. This scan can provide critical information such as the location, size, and extent of the syrinx, a fluid-filled cyst in your spinal cord. An MRI can also help determine the extent of any displacement of the brain tissue (cerebellar tonsillar ectopia).

In addition to detailing the syrinx, MRI can show if the fluid spaces at the back of the brain are getting compressed, a common feature in patients with a related condition called Chiari Malformation type 1 (CM-1). The MRI can also make sure there aren’t any cyst-like structures or tumors in the spine, and it can spot signs of infection or scar tissue. By taking MRI scans over time, your doctor can track the development of syringomyelia, providing a better understanding of how the condition changes.

Another type of MRI called phase-contrast MRI, also known as a Dynamic MRI or Cardiac-Gated Cine MRI Flow Study, may be employed. This advanced technique can examine the details of any disturbances in the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the fluid that surrounds your brain and spinal cord, and can track the movement of fluid in the syrinx during heartbeats while at rest. This test is also helpful in documenting any improvements after surgery.

Sometimes, if an MRI is not an option due to certain situations such as having metallic joint implants or cardiac pacemakers, a procedure called a Myelography with High-Resolution Computed Tomography (CT) scan may be utilized. This imaging technique can show if dye has leaked into the syrinx cavity. However, its ability to detect blockages in CSF, is less superior when compared to an MRI.

A test known as electromyography might also be used, not as a diagnostic tool for syringomyelia, but to rule out other conditions like peripheral neuropathy, which could also cause unusual sensations, known as paresthesias.

These tests categorize syringomyelia into four types—distended, moniliform type (continuous partitions ≥3), slender type, and circumscribed to help the physician choose the best treatment strategy.

Treatment Options for Syringomyelia

When it comes to treating syringomyelia, a condition where fluid-filled cysts form within the spinal cord, it’s important to avoid activities that place additional strain or pressure on the veins. These include bending the neck, straining, or holding your breath for prolonged periods. Reducing such pressure can help relieve some of the related symptoms.

In many cases, children with syringomyelia may see their symptoms disappear naturally as they grow and the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which cushions the brain and spinal cord, is restored. In adults, spontaneous healing can also occur due to factors such as the natural breaking up of scar tissue in the spinal cord, drainage of cysts into the spinal fluid space, or age-related brain shrinkage.

When it comes to medical interventions, the intent is to correct the issues causing syringomyelia and improve the flow of CSF fluid. For patients with Chiari Malformation Type 1 (a condition where brain tissue extends into the spinal canal), a procedure called craniocervical decompression is often recommended. This involves making more room at the back of the skull and the top part of the spinal column to alleviate pressure. Surgery works best when performed early, as the longer a patient experiences symptoms, the less beneficial the surgical intervention will be.

In cases where syringomyelia is a result of inflammation and scarring or a past injury, surgery aims to restore the proper flow of spinal CSF fluid via the removal of scar tissue and reconstruction of the dura, the outermost of the three layers of the meninges that surround the brain and spinal cord.

Shunts, devices that reroute the CSF, may be considered for idiopathic syringomyelia, a condition that arises without a clear cause, or when others treatments haven’t been effective. While some studies suggest better results with the syringosubarachnoid shunt compared to other methods, this perspective is not universally accepted. Shunts are generally considered a last resort due to their high rates of complications and failure, as well as their inability to address the underlying cause of syringomyelia.

Some of the indications for surgery include symptomatic Chiari Malformation Type 1 with syringomyelia, symptomless Chiari Malformation Type 1 with worsening conditions, and post-traumatic syringomyelia with motor deficits.

Before surgery, doctors must evaluate a patient’s intracranial compliance, which is essentially the brain’s ability to adapt to changes in pressure. In some instances, especially when the compliance is low, patients may undergo a ventriculoperitoneal shunt before foramen magnum decompression. This treatment has shown to reduce syringomyelia in about 80% of cases.

Various other treatment measures might be considered. For example, when an excessive accumulation of CSF in the brain (hydrocephalus) is also present, measures to relieve the pressure on brain tissue may be required. Endoscopic fenestration, a minimally invasive procedure used to drain fluid from brain cavities or cysts, can also be considered. Other related conditions, such as a tethered spinal cord, will also need to be treated. Occasionally, more invasive shunting procedures may be required if these interventions are not enough.

What else can Syringomyelia be?

When considering a diagnosis, the following conditions should also be taken into account:

- Spinal intramedullary tumors: Conditions like hemangioblastoma, ependymoma, and gliomas may generate a fluid with high protein content. This fluid can lead to microcysts that, over time, can merge together. Most of these tumors make their presence known on contrast MRI scans – unlike a syrinx, which doesn’t show up on these scans – although a genuine syrinx can occur within a tumor.

- Spinal intramedullary cysts, myelomalacia, arachnoid cysts, and glioependymal cysts: These are various types of cysts or damages that can occur in the spinal cord.

- Residual central spinal canal: The central canal of the spinal cord may shrink with age, and a remaining central canal is not viewed as abnormal.

What to expect with Syringomyelia

Syringomyelia is a condition with a varying and unpredictable course that makes it challenging to provide a definite prognosis or forecast of the disease. The future progress of the condition depends on several factors such as the underlying cause, the extent of nerve damage, the location and size of the syrinx cavity (fluid-filled cavity within the spinal cord), and a syrinx diameter larger than 5 mm. Other factors like associated swelling often indicate a quick worsening of the disease. However, prompt surgical treatment can improve the condition and reduce the severity of the disease.

Past studies indicate that a surgical approach called posterior fossa/foramen magnum decompression has been the primary procedure employed. This operation led to improvement or total resolution of syringomyelia in almost 80% of patients. Another safe and efficient treatment strategy involves a procedure called small-bone-window posterior fossa decompression with duraplasty, which has a low complication rate. Furthermore, foramen magnum decompression and duraplasty result in considerable and sustained improvements in both clinical and radiological outcomes. Interestingly enough, the reduction of the syrinx or adjustments in the position of the cerebellar tonsillar don’t affect the clinical outcomes. However, restoration of normal spinal fluid flow at the junction of the skull and neck has shown a stronger association with better outcomes.

Size, length, and number of syringomyelia are not critical to the prognosis. Still, a reduction in size of the syrinx often leads to a high likelihood of motor improvement compared to sensory disturbance and pain. Generally, motor dysfunction, displacement of a part of the brain, and an inward bulging at the base of the skull indicate a poor clinical prognosis. On the other hand, patients with syringomyelia located in the neck region often have better functional recovery after the right intervention.

Regarding posttraumatic syringomyelia, a variant called moniliform shows a better prognosis. It usually affects individuals aged 30 and older with severe spinal cord injuries and commonly manifests in the neck region within 5 years post-injury. Surgery, particularly arachnoid lysis and syrinx drainage, is performed in nearly 90% of cases. About 43% of patients noted improvement in their symptoms post-surgery. There is approximately a 70% survival rate ten years after a traumatic spinal cord injury-induced syringomyelia.

In some instances, preventive neurosurgery might help avoid the need for spinal curvature correction surgery in patients with a large syrinx. However, in 10% to 50% of cases, syringomyelia may persist, recur, or worsen even after undergoing posterior fossa decompression. In such cases, further interventions may be recommended, including repeat posterior fossa decompression, atlantoaxial fusion surgery, or treatments for local spinal pathologies such as fractures, tumors, and cysts.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Syringomyelia

Myelopathy is a severe complication that can occur due to disease. It can lead to excessive muscle tension, and in severe cases, it can even cause paralysis. Other conditions associated with this can include pressure ulcers, repeated cases of pneumonia, along with problems in bowel and bladder function. Sometimes, it can also lead to nerve-related pain and joint issues.

Kyphoscoliosis is a condition where there is a reduction in the length of the spine.

In a certain study, it was found that nearly 41% of patients faced complications after surgery. Some of the more common complications included leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), abnormal fluid-filled sac (pseudomeningocele), infection-free meningitis, wound infection, meningitis, and neurological impairments. The complication rate came around 4.5% as an average. Mortality rates accounted for 11% in this study, and it was found that there was no noticeable difference between child and adult patients.

Possible Complications:

- Excessive muscle tension (spasticity)

- Paralysis (paraplegia/quadriplegia)

- Pressure ulcers (decubitus ulcers)

- Repeated pneumonia

- Problems in bowel and bladder function

- Nerve-related pain (neuropathic pain)

- Joint issues (neuro-arthropathy)

- Leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF leak)

- Abnormal fluid-filled sac (pseudomeningocele)

- Infection-free meningitis (aseptic meningitis)

- Wound infection

- Meningitis

- Neurological impairments

- Potential death (mortality rates)

Preventing Syringomyelia

Patients should understand the following advice for dealing with certain medical conditions:

* If you have syringomyelia that hasn’t been treated, you need to be careful about doing any activities that could put pressure on your brain or abdomen. This includes not pushing too hard when you go to the bathroom, not lifting heavy things, avoiding coughs and sneezes as much as you can. Doing these things can make the condition worse by making the abnormal fluid-filled cavity in your spinal cord bigger. This advice is especially important just after having surgery, especially if you’re taking strong pain killing medicine that can make you constipated. If you notice symptoms like a constant cough or constipation, you should get in touch with your doctor right away.

* If you have a Chiari malformation, a condition where brain tissue extends into your spinal canal, you should stay away from activities that put a lot of strain on your neck. This means you should avoid things like roller coasters, trampolines, and contact sports like football. Instead, you can do exercises that are safer like swimming, stationary biking, and yoga.

And remember, if at any time after surgery, you notice any pus-like fluid coming out of where you had your operation, or signs of infection like a painful, swollen, or red wound, you should tell your doctor immediately.