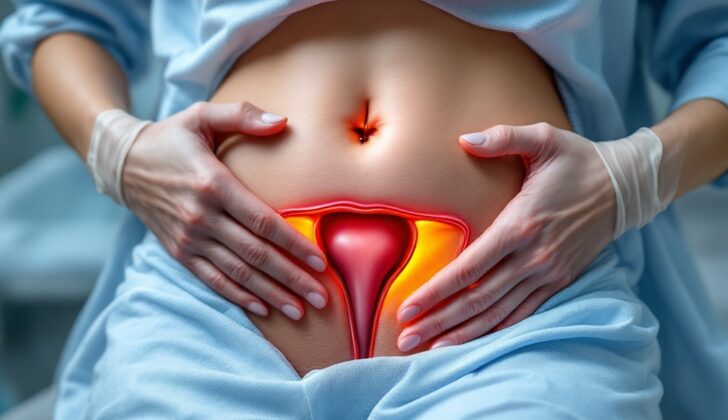

What is Pelvic Organ Prolapse?

Pelvic organ prolapse is a condition where the organs in the pelvis, such as the uterus or bladder, drop into the vagina because of weak muscles or supportive tissues. This condition can happen in different areas and is classified based on where the descent occurs. A ‘cystocele’ is when the front wall of the vagina presses downward, a ‘rectocele’ is when the back wall of the vagina drops down, and a ‘vaginal vault prolapse’ is when the uterus, cervix, or top of the vagina comes down. These can occur one at a time or in combination.

Many factors can lead to pelvic organ prolapse, including, notably, pregnancy and vaginal birth, which can cause damage to the pelvic floor muscles and tissues. Other causes include previous pelvic surgeries or situations that repeatedly increase pressure inside the abdomen. These might involve heavy lifting, being overweight, a chronic cough, or constipation.

Most of the time, women with prolapse may not display any symptoms. However, if the pelvic organs drop far enough to protrude past the vaginal opening, symptoms might become troublesome. When diagnosing this condition, doctors carry out a detailed medical history and a thorough pelvic exam. They also assess for complications such as urinary leakage, difficulties passing urine, or bowel leakage.

Treatment strategies depend on how severe the prolapse is and what symptoms it causes. They can range from simple monitoring, using devices known as vaginal pessaries to help support the prolapsed organs, or in some cases, surgical intervention. Surgery can be reconstructive to restore the normal position of the pelvic organs, sometimes with added support from a mesh, or obstructive to narrow or close off the vagina.

What Causes Pelvic Organ Prolapse?

Normal pelvic support, or the structure of a woman’s lower torso, relies on the combined workings of a group of muscles called the levator ani muscle group and the tissues connecting and stabilizing the vagina. If these tissues weaken or tear, it could lead to issues in the pelvic floor, which is the area that encompasses the bladder, bowel, and uterus.

When the pelvic support is working properly, the vagina is positioned horizontally above these muscles. However, when damage occurs, the levator ani muscles shift to a more vertical position. This opens up the vagina more, causing its supportive duties to be transferred towards the connecting tissues.

It’s also speculated that during the second phase of labor, these levator ani muscles could stretch more than two times their usual limit, which can potentially lead to injury.

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP), a condition where one or more of the pelvic organs drop from their normal position and may protrude into the vagina, often occurs due to a combination of factors. These can include a person’s anatomy, physiology, genetic makeup, lifestyle, and reproductive factors. As such, issues with the pelvic floor can occur at any point of a woman’s life. Multiple studies have also indicated that women who have given birth multiple times are more likely to suffer from POP.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Pelvic organ prolapse commonly increases with age. Women who experience it often suffer physically and emotionally. This can lead to negative effects on their social, physical, and psychological well-being. While we don’t know the exact number of cases, yearly data from hospital procedures reports around 200,000 surgeries for treatment each year in the United States. Even though between 41% to 50% of women are found to have pelvic organ prolapse during physical examinations, only about 3% show symptoms. The number of women with pelvic organ prolapse is expected to rise by 46%, reaching 4.9 million, by 2050.

Signs and Symptoms of Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Pelvic organ prolapse is a condition where organs drop down or push into or out of the vagina. Many women with this condition don’t feel any symptoms. However, some women may feel a bulge sticking out through the opening of the vagina. This sensation can sometimes make a woman feel embarrassed or uncomfortable during her yearly checkup. That’s why it’s crucial for doctors to proactively ask about any such feelings during these visits.

To diagnose pelvic organ prolapse and determine its type, a physical examination is necessary, which might be affected by how full the bladder and rectum are. Women with advanced prolapse can experience vaginal discharge due to vaginal chafing or tissue damage. Furthermore, pelvic organ prolapse often comes with other pelvic floor disorders. For instance, 40% of these women also have urinary incontinence, 37% have an overactive bladder, and 50% experience fecal incontinence. Therefore, routine screening for other possible conditions is essential. In some cases, the prolapse can hide stress urinary incontinence.

Pelvic organ prolapse can also block the bladder outlet due to kinks in the urethra, or increased urethral pressure. This condition can impact sexual activity, self-image, and overall quality of life. That’s why doctors should always check for signs of this condition, since many women might feel too embarrassed to mention their symptoms.

Health care providers will perform a thorough pelvic examination to identify the type and degree of the prolapse. The examination involves asking the patient to perform the Valsalva maneuver (this is like trying to blow the air out of your nose while holding it closed), while they check the perineal body (the area between the vagina and rectum) and the vaginal opening for any apical prolapse (where the top of the vagina droops). Then a speculum is used to get a clearer view of the top end of the vagina. Using a 1-blade sims speculum (a tool to gently open the vagina), they examine the front and back walls of the vagina to check for cystocele (bladder prolapse) and rectocele (rectal prolapse), respectively. The degree of the prolapse can be measured using the Baden-Walker grading system or the pelvic organ prolapse quantification system, which can help with assessing the condition clinically.

Testing for Pelvic Organ Prolapse

If your doctor suspects you might have pelvic organ prolapse (POP), they would need to check for signs of infection, blood in the urine (hematuria), and whether your bladder is fully emptying. They may recommend something called a urodynamic evaluation if you have serious symptoms when urinating. This evaluation helps them understand how well your bladder and the muscles that control urine flow (sphincters) are working.

In people with severe prolapse, a common problem is detrusor dysfunction, which results in a high amount of urine left in the bladder even after urination. During the urodynamic evaluation, your doctor might reduce the prolapse to assess the function of the sphincter muscles properly. This can also help uncover stress urinary incontinence, which is a condition where you may leak urine when you sneeze, cough, or do other physical activities. The sneezing or coughing essentially “un-kinks” the tube that carries urine from the bladder (urethra), revealing the incontinence that might have been missed otherwise.

If you have severe prolapse (procidentia), you might need to have an imaging scan of your kidney and ureter (the tube that carries urine from the kidney to the bladder) called a computed tomography (CT) urogram. In severe prolapse cases, the descent of the bladder can pull on the ureters and distort the pelvic anatomy, particularly the right ureter. This can lead to blockage and swelling of the kidney (hydronephrosis).

Treatment Options for Pelvic Organ Prolapse

If a woman is experiencing pelvic organ prolapse (a condition where pelvic organs like the uterus, bladder, or rectum droop into or out of the vagina), there are different ways to manage it. The choice will depend on her age, whether she wants to have children in the future, her sexual activity, the severity of her symptoms, and her general health. Different methods also work better depending on which organ has descended.

If a woman has only mild symptoms, regular check-ups might be enough. Many women with this condition don’t experience noticeable symptoms until the organ in question protrudes out of the vagina. In these cases, doing pelvic floor muscle training (known as Kegel exercises) can sometimes help control the symptoms. These exercises involve contracting and releasing the muscles in the pelvic floor and have been proven to help with certain types of incontinence (the uncontrollable loss of urine or stool).

Many women with noticeable symptoms opt to use a device called a pessary. This is often made of medical-grade silicone and is placed inside the vagina to help support the organs. Pessaries can be used for any stage of prolapse and can be useful in delaying the need for surgery. However, they can be hard to fit properly in women with short vaginal length, a wide vaginal opening, or a history of hysterectomy (surgery to remove the uterus). It’s often necessary to clean these devices regularly, which can involve removing and reinserting them.

In cases where surgery is necessary, it’s important to discuss a woman’s future childbearing plans and expectations before proceeding. Several types of procedures can be done to help restore the function of the pelvic floor and eliminate symptoms. Some women may choose a procedure called a colpocleisis, which shortens the vagina. This procedure has a high success rate, but it makes sexual intercourse impossible, so it’s important to discuss this ahead of time.

For women who want to maintain sexual function, there are several different surgical procedures that might be appropriate. Some of these surgeries work by fixing the tissues and ligaments already present in the woman’s body, while others involve using donated tissues or synthetic materials to provide extra support. The best choice will have to be determined by the woman and her doctor based on her individual circumstances and priorities.

An iliococcygeus suspension, a procedure that attaches the vagina to the muscle of the same name, has a noteworthy success rate. Another surgical technique, the uterosacral suspension, which attaches the vaginal cuff to the uterosacral ligaments in the midline, also has shown promising results. However, due to close proximity to the ureters (tubes that carry urine from the kidneys to the bladder), there might be some risk involved with this approach.

In recent years, a procedure called abdominal sacrocolpopexy has become favored. This can be done either through a large incision in the abdomen (laparotomy), through smaller incisions with the aid of a camera (laparoscopy), or with assistance from a robotic surgical system. It involves anchoring suspensory mesh to the sacrum (the triangular bone at the base of the spine). The mesh is typically made from non-absorbable material, and has shown to provide long-term relief from the symptoms and restores vaginal functionality. This procedure is a top choice for women who wish to maintain vaginal function or those who have had previous failed operations.

What else can Pelvic Organ Prolapse be?

Even though pelvic organ prolapse (POP) may appear quite distinctive in its symptoms, there have been cases where it’s been mistaken for other medical conditions. When a health professional notices symptoms such as a bulge during a check-up, they might need to consider a few other possibilities. These could include:

- Vaginal cysts

- Cervical polyps

- Elongation of the cervix

- Tumors of the urethra or bladder

- Large urethral diverticulum

- Skene gland cysts

What to expect with Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Pelvic organ prolapse, while inconvenient, is not life-threatening. At first, most people with this condition don’t feel any symptoms. Those who do experience a bulging sensation often see their symptoms improve significantly with the use of pessaries (a type of medical device inserted in the vagina to support pelvic organs) and other non-invasive treatments.

Surgery to treat pelvic organ prolapse has a high success rate, roughly 95%. Studies looking at patients two and five years after surgery show that there’s a significant reduction in their symptoms and minimal new health problems occurring.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Pelvic organ prolapse can sometimes cause urinary issues. When diagnosing pelvic organ prolapse, it’s important to check for signs of hidden urinary incontinence. Pelvic organ prolapse can also lead to problems with bowel movements, sometimes making it necessary for the patient to use a finger for assistance.

A common treatment for pelvic organ prolapse is using a device called a pessary. This treatment usually works well, but there are possible complications that patients should be aware of. These might include symptoms like vaginal discharge, irritation, sores, bleeding, pain, and bad smell. Sometimes a pessary can even lead to complications like sores on the vaginal wall, fistula formation, or a hernia. Women who do not change their pessaries at least once a week are more likely to develop bacterial infections. Sores and bleeding in the vagina are possible complications of using a pessary, especially in postmenopausal women and in cases where the pessary is not removed frequently.

Possible Complications of Pessary Use:

- Vaginal discharge

- Irritation

- Sores

- Bleeding

- Pain

- Bad smell

- Sores on the vaginal wall

- Fistula formation

- Hernia

Mesh insertion is another treatment for pelvic organ prolapse, but it has been linked to complications. There has been controversy about the use of transvaginal mesh and biological grafts in prolapse surgery. Recently, the FDA has limited the use of large mesh grafts for treating pelvic organ prolapse to native tissue or biological grafts. Complications with mesh can include infection and pain during intercourse. Mesh with small pore sizes can lead to high infection rates as bacteria can get in, but macrophages can’t.

Possible Complications of Mesh Insertion:

- Infection

- Pain during intercourse

- High infection rates due to small pore sizes

Preventing Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Talking to patients about how common pelvic organ prolapse is can help reduce stigma and the related emotional issues that often cause delays in diagnosis. The International Urogynecology Association (IUGA) and the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) have created helpful materials and information that patients can print out. These resources explain the symptoms, the steps involved in diagnosing the condition, and the different treatment options available.

They also provide guides on how to care for pessaries – devices used to treat pelvic organ prolapse- at home. These guides have been very effective in reducing complications related to the use of pessaries and have also helped patients feel more confident about their treatment.