What is Perilunate Dislocation?

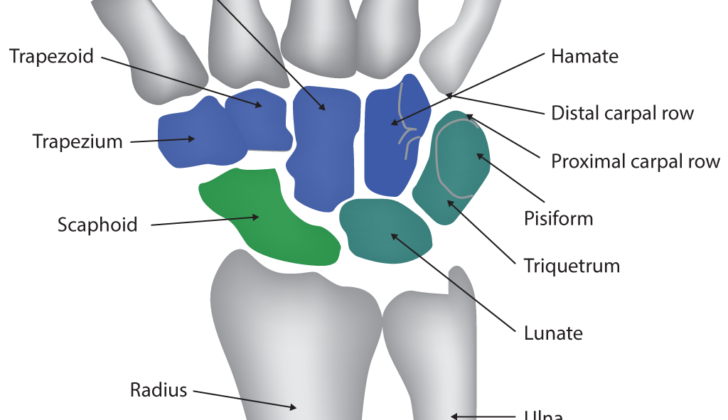

Perilunate dislocations, lunate dislocations, and perilunate fracture-dislocations are severe but rare injuries that make up less than 10% of all wrist injuries. The wrist is made up of two rows of bones. The first row, the proximal, is more mobile and moves together with the lower parts of the arm bones. This row is made up of the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum bones. The second row, the distal, is more rigid and includes the trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate. This row connects the first row to the base of the fingers. The strength of the wrist comes from how these bones connect and the ligaments supporting them.

The lunate bone, which is shaped like a crescent moon, is a particularly important part of the wrist. It serves as the central link between the forearm and the hand. Ligaments attach it to surrounding bones and help keep the wrist stable.

Perilunate dislocations typically happen when the bones or ligaments around the lunate bone get injured. These injuries can cause the other wrist bones to displace, usually in the direction of the back of the hand, while the lunate bone stays put. At times, however, the lunate bone can move towards the palm. These injuries can lead to persistent wrist disability. As a result, it is important to identify and treat them early to avoid long-term damage. Early intervention can also reduce the risk of nerve injury, arthritis, chronic instability, and improperly healed fractures. Non-surgical treatment is rarely effective and can lead to poor function and recurring dislocation of the wrist.

What Causes Perilunate Dislocation?

Research into the movements and forces of the body shows that Perilunate Dislocations (PLDs) typically happen because of a sharp overstretching, bending towards the pinky finger side, and twisting of the wrist. PLDs are commonly seen in situations involving high-impact injuries, like car crashes, falls, sports injuries, or accidents at work.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Perilunate Dislocation

Perilunate dislocations (PLDs) are often overlooked, making it hard to know their true frequency. They don’t have their own specific code for diagnosis, which means they are put under the category of mid-carpal joint dislocations in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9 and ICD 10. This grouping makes it challenging to collect data about these injuries.

Generally speaking, fractures or dislocations in the wrist joint are not as common as fractures in the lower arm, the hand bones, or the finger bones. Each year, wrist fractures and dislocations have a rate of 37.5 per 100,000 people, making up 2.8% of all fractures. It’s estimated that less than 10% of all wrist injuries are perilunate injuries.

Signs and Symptoms of Perilunate Dislocation

Perilunate dislocation (PLD) is an injury to the wrist region that often gets overlooked in around 25% of cases during routine physical and imaging tests. The failure to identify the condition can lead to severe complications. People with PLD usually experience a decrease in their ability to move the wrist, swelling, pain, and an abnormal shape or lump in the wrist. The specific symptoms can differ depending on how severe the injury is.

When the smaller bones (distal) of the wrist separate towards the back side (dorsally), a visible deformity may be seen at the wrist. Conversely, if the lunate bone (a bone in the wrist) dislocates towards the palm (volar), a lump or deformity can be felt within the wrist area.

A full history and examination of the injury helps to better understand how it happened and to check for other possible associated injuries, which could appear in around 26% of cases. A thorough examination of the nerves and blood vessels of the affected arm is crucial. PLDs have been found to be associated, in around 29% to 45% of cases, with an acute condition causing numbness and tingling in the wrist and hand, known as carpal tunnel syndrome. As a result, patients who suffer from the compression of their median nerve, which runs through the wrist, may report a tingling sensation on the palm side of their first three fingers. However, the assessment of how well the hand functions could be limited due to the pain associated with the condition.

Testing for Perilunate Dislocation

After a comprehensive health history and physical exam, it’s helpful to use imaging tests for further diagnosis. Regular x-rays should be taken from different angles, such as front-to-back (PA), side, slanting, and focused on the specific wrist bone (scaphoid). Every image should be carefully examined for any oddities. Certain typical x-ray abnormalities may be spotted. For example, on the PA view, if there is more than 3 mm space between two specific wrist bones, it may suggest a ligament injury. This is known as the Terry Thomas sign. Additionally, if the normal arched lines (Gilula lines), which track along the wrist bones, are not aligned as they should be, it might indicate wrist injuries.

The lunate bone (one of the wrist bones) can look triangular if it has moved out of position. This is referred to as the “piece-of-pie sign.” The side-view x-ray should reveal if there is a straight line from the edge of the forearm’s bone, through the lunate, another wrist bone called capitate, and the bone of the third finger. Any break in this line can point to wrist instability or misalignment. Furthermore, from the side view, one might observe the “spilled teacup sign,” which is seen when the lunate bone has slipped forward.

For a better understanding of the fractures, a CT scan can be helpful. Not only can it offer a glimpse into the character of the fractures, it can also aid in surgical planning. Using CT images for 3D reconstruction has increasingly become beneficial for surgeons. For accurately identifying ligament injuries and “hidden” fractures not visible on regular x-rays or CT scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is found to be both sensitive and specific. Advanced imaging like an MRI should ideally be done after the correction of the misaligned bones.

Treatment Options for Perilunate Dislocation

The initial way to handle dislocations of the wrist bones (also known as perilunate dislocations, PLDs) is by manipulating the wrist back into place, a procedure called a closed reduction. This is often a difficult process and might involve applying weights to the arm for traction and hanging the hand in the air to balance the forces. Often, the person might need to be sedated to make the procedure more successful.

The specific method used in the reduction depends on the exact type of dislocation. For dislocations where the lunate bone has moved towards the palm of the hand (volar LDs), the wrist is straightened out, while at the same time, a force is applied to the lunate bone in the opposite direction to push it back into place. The wrist is then flexed while keeping this force on the lunate bone. For certain PLDs where the lunate remains in place but the other wrist bones have moved away, a similar method is used to get these bones back in line with the lunate. After the reduction, the wrist is put into a splint to immobilize it.

Research, however, hasn’t shown great results with just this kind of treatment. Generally, surgery is needed to make sure the wrist is properly aligned, fix any damaged ligaments, deal with any associated fractures, and stabilize the wrist to allow the ligaments to heal. The surgery could be performed from the palm side, the back side, or both sides of the wrist, and usually includes a procedure to relieve pressure on the nerves in the wrist (carpal tunnel release). Although surgery is generally agreed upon, there is some disagreement on the best surgical approach, and so the choice often comes down to the surgeon’s preference.

If these dislocations aren’t treated early enough or if they are missed and become chronic, there are two common methods to deal with them. One is to try an open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF), a procedure where the surgeon directly manipulates the bone back into place and uses metal hardware to keep it there. The other option is to remove certain bones or fuse them together, or in some severe cases, to fuse the entire wrist joint.

What else can Perilunate Dislocation be?

If your wrist hurts after an injury, it might be because of a variety of underlying issues. Some of these include sprains or tears in the ligaments inside or outside your wrist, injuries to the triangular fibrocartilage complex (a small cartilage structure in your wrist), damage to the cartilage, instability in the lunotriquetral ligament (one of the key ligaments in the wrist), or a condition called scapholunate dissociation where two bones in the wrist separate from each other.

Often, doctors would use x-rays or similar imaging techniques to check for broken bones in your wrist. The most common break happens in the scaphoid bone – a small bone located on the thumb side of your wrist. Fractures might also happen in the distal radius (the end of the bigger bone in your forearm) or the base of your hand bones.

Remember that the right treatment completely depends on the accurate diagnosis of what’s causing your wrist pain. This highlights the necessity for doctors to consider all possible causes when diagnosing a wrist injury.

What to expect with Perilunate Dislocation

Perilunate dislocations (PLDs) are serious wrist injuries and patients should be fully aware of the severity. Studies have shown that non-surgical treatments don’t tend to be as effective as surgical treatments. One research examined 28 patients with PLD, found that those treated without surgery experienced fair to poor results over a six-year period. The rest of the patients, treated with surgery, had positive results.

However, even with prompt treatment and fitting, some factors can complicate recovery and lead to less than ideal results. By reviewing 166 cases of PLD, some key factors that influence the outcomes were identified. Open injuries treated within a week of the accident had lower average clinical scores compared to those treated later.

Looking at X-rays, 71% of patients had ongoing unsatisfactory images, and 56% showed signs of post-trauma arthritis, which surprisingly wasn’t linked to poor clinical outcomes. Yet, all of the satisfactory X-rays correlated with good or excellent results. Another study showed that on average, patients regained 68% to 80% of movement and 70% of grip strength compared to the undamaged hand. About 70% showed arthritis in X-rays, but its impact seemed to be low based on functional scores. The most alarming result was that 20% of patients developed complex regional pain syndrome, which can cause severe disability.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Perilunate Dislocation

Perilunate dislocations (PLDs) and perilunate fracture dislocations (PLFDs) can lead to several complications. One common issue is acute median neuropathy, which often results in acute carpal tunnel syndrome that requires surgical intervention. This condition is most prevalent in Stage IV injuries when the lunate, a small bone in the wrist, dislocates into the carpal tunnel. Other complications include persistent irritation of the median nerve, post-traumatic arthritis, temporary decreased blood supply to the lunate, death of bone tissue, loss of cartilage, chronic instability in the area around the lunate, and complex regional pain syndrome.

These complications can lead to poor patient outcomes, so they should be closely monitored in those recovering from PLDs and PLFDs.

- Acute median neuropathy

- Acute carpal tunnel syndrome

- Persistent median nerve irritation

- Post-traumatic arthritis

- Temporary lunate ischemia

- Osteonecrosis (bone tissue death)

- Chondrolysis (loss of cartilage)

- Chronic perilunate instability

- Complex regional pain syndrome

Preventing Perilunate Dislocation

It is important to educate patients, the general public, and healthcare providers to get the best possible health outcomes. This is based on the fact that information and knowledge often result in better care, as supported by evidence-based medicine.