What is Radial Head Dislocation?

It’s not common to find a case of a dislocated radial head, which is a part of the elbow. Usually, when this happens, it’s a partial dislocation or subluxation, often called a “nursemaid’s elbow”, which typically occurs in children. The complete dislocation of the radial head is quite rare and normally happens due to severe arm injuries. This dislocation often comes with a forearm fracture or another misplacement of the arm bones. To correctly evaluate such injuries and avoid complications from a missed diagnosis, doctors use a combination of patient history, physical examination, and medical imaging.

While correcting a partially dislocated radial head is usually a straightforward procedure, if a completely dislocated radial head was missed or ignored, it would require surgery. This is because it’s often accompanied by fractures in the ulna – one of the main bones in the forearm – as well as other complications.

What Causes Radial Head Dislocation?

The annular ligament is key in keeping the radial head (part of your elbow) stable. In children, if the forearm is pulled while it’s straight and twisted outward, it can cause the annular ligament to move out of its place over the radial head, a situation known as subluxation. But, this ligament might not always move out of place. Instead, under high-force injuries commonly seen in both children and adults, it can tear resulting in complete radial head dislocation.

In some less frequent cases, despite the high-force injury, the annular ligament may remain unharmed and still connected to the nearby lateral collateral ligament and the ulna (another bone in the forearm). In such situations, it’s the radial head that slips under the annular ligament instead.

Risk Factors and Frequency for Radial Head Dislocation

Dislocation of the radial head (a part of the elbow) on its own is very rare and doctors often overlook this injury. The more common type of radial head dislocation moves towards the front and is usually coupled with other injuries, like fractures in the ulna (a bone in the forearm). The chance of having this combination of injuries is less than 2% among all forearm fractures. While rare, this injury is more common in children aged 4 to 10 years than in adults. Elbow dislocations represent a considerable portion (10 to 25%) of elbow injuries, particularly among individuals aged 10 to 20 years.

There’s also such a thing as a congenital (present from birth) radial head dislocation, and it is exceedingly uncommon. This condition is usually associated with the radial head moving towards the back and other concurrent birth defects. In these individuals, the radial head dislocation can occur in both arms and does not result from trauma. Most of the time, these cases do not have symptoms.

Signs and Symptoms of Radial Head Dislocation

When diagnosing an elbow injury, it’s important to have a detailed sequence of events. Doctors should understand how the injury happened, whether there was any form of trauma, and the movements involved like pulling, twisting, or rotating the arm. It’s also crucial to know if there’s a history of any congenital diseases which could impact the diagnosis.

For a child with a partially displaced annular ligament, they will typically keep their arm in an extended and pronated position to protect it. The injury causes pain over the radial head area of the elbow, leading the child to avoid using their arm and keep it close to their body. There usually isn’t any swelling, bruising, or deformities, but the child will resist any attempt to move their forearm.

When dealing with a radial head dislocation due to a traumatic injury, some signs to look out for include deformities, swelling, compromised nerve and blood supply, and differences in limb length when compared to the other arm. A restricted joint movement should also raise suspicion. Range of motion tests can help diagnose this, especially if elbow flexing is limited due to an anterior radial head dislocation. In some cases, the protruding radial head may become visible and palpable, compelling parents to seek medical advice.

For individuals with a congenital dislocation, they normally don’t show any symptoms until their teenage years. Typical signs include elbow locking or movement restriction without any past trauma events.

Testing for Radial Head Dislocation

When dealing with an injury to the arm, doctors need to perform a thorough examination which includes looking closely at the arm, feeling it and assessing its motion. Checking for any nerve damage is also key. In the case of a traumatic arm injury, imaging scans are essential to check not just the injured joint, but also the joints above and below it. While a standard X-ray is a quick way to assess an acute injury, an ultrasound can also be helpful. For more complex injuries, other tools like computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be needed.

One particular type of injury is called a Monteggia injury. This involves a dislocation of the radial head (round top of the radius bone in the forearm) and a break in the ulna bone of the forearm. People with this kind of injury usually experience pain, swelling and reduced movement at the elbow due to the dislocation of the radial head. They could also lose the ability to use their extensor muscles as a result of nerve injury. Doctors classify these fractures into four types, depending on the direction in which the radial head is displaced:

– Type I: A break in the upper or middle third of the ulna along with an anterior (frontwards) dislocation of the radial head (seen most often in children and young adults)

– Type II: A break in the upper or middle third of the ulna and posterior (backwards) dislocation of the radial head (mostly seen in adults)

– Type III: A fracture of the ulnar metaphysis (near the elbow joint) and a lateral dislocation (outwards) of the radial head

– Type IV: A fracture of both the radius and ulna in their upper or middle thirds, with the radial head being displaced in any direction.

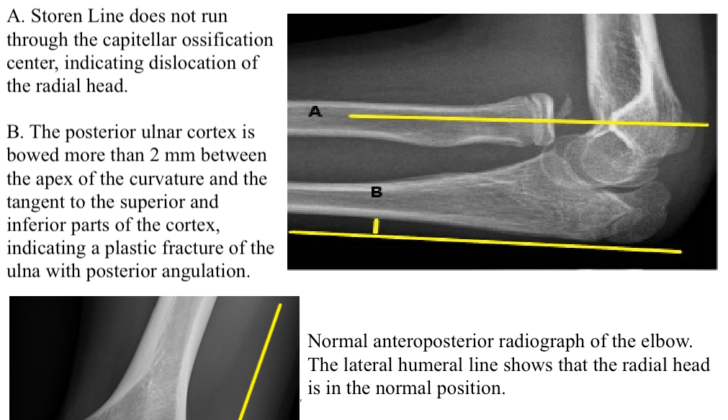

To avoid overlooking a radial head dislocation, doctors need to create what’s known as a Storen line, checked on a lateral (side) view of the elbow. If this line goes through a particular part of the elbow joint, it suggests that the radial head hasn’t been dislocated. There are also other radiology tools like the “ulnar bow sign” and the “lateral humeral line” drawn on X-rays that help in diagnosing these injuries.

Congenital (from birth) dislocations of the radial head usually do not cause any symptoms. However, they can make the radial head seem prominent and limit the elbow’s ability to extend and twist outwardly. Doctors diagnose these based on specific features seen on X-rays, such as e.g. a relatively short ulna or long radius, an underdeveloped or missing elbow joint, a prominent bony point on the elbow, a groove in the lower part of the radius, or a dome-shaped radial head with a long, narrow neck.

Treatment Options for Radial Head Dislocation

The radial head, located in the elbow, most commonly dislocates toward the front of the body. However, depending on the injury and force applied, it can also displace to the side or back. The annular ligament is the key structure that keeps the radial head in place and prevents it from dislocating. Other ligaments in the upper part of the forearm also contribute to keeping the joint stabilized.

In an emergency setting, the primary treatment for a recent ulna (inner lower arm bone) fracture that is combined with a radial head dislocation is sedation followed by manual realignment of the ulna. This process usually helps to relocate the radial head as well. After a successful realignment, doctors should check the stability of the radial head using fluoroscopy, a type of medical imaging. Following this, the elbow should be placed in a full-arm cast for six weeks. The exact position of the forearm in the cast depends on what position best stabilizes the radius (outer lower arm bone) and ulna.

Children often recover well with just the manual realignment. However, if the stability of the realigned ulna fracture is in doubt, it may require internal fixation – a surgical procedure to stabilize a bone. Kids with dislocations of the radial head that cannot be manually realigned, or that have been overlooked and have become established, will typically require surgery. In adults, open surgical repair is almost always necessary.

A number of surgical approaches are available for treating chronic dislocations of the radial head, the most common involves manually realigning the dislocated part followed by stabilizing the ulna with a plate, screws or a rod inserted into the marrow of the bone, and reconstructing the annular ligament.

In cases of congenital radial head dislocation – that is, those present from birth – intervention is usually only needed much later in life when significant elbow pain or limited motion become issues. In these situations, surgical removal of the radial head can significantly help to alleviate pain in selected patients.

What else can Radial Head Dislocation be?

When a child has a condition known as “nursemaid’s elbow”, it can often be mistaken for other issues. These can include:

- A fracture near the elbow

- Other types of fractures, like in the collarbone or wrist, which can be harder to diagnose in young children

- An infection in the elbow joint

- A neurological injury

- Even child abuse, in some cases

A similar condition called “radial head dislocation” can also be confused with other problems. These might include:

- Bones being broken near the upper arm or elbow, called the proximal ulna and radius or the distal humerus

- An injury called Essex-Lopresti

- A soft tissue injury in the elbow area

- Bursitis (inflammation in the elbow)

- Fluid build-up or an infection in the elbow joint

- Arthritis or a bone infection in the elbow (osteomyelitis)

- A deep tissue abscess caused by IV drug use

- A neurological injury

Remember, it’s very important that the correct diagnosis is made to ensure that the patient receives the right treatment. Misdiagnosis could lead to delayed treatment and further complications.

What to expect with Radial Head Dislocation

The successful fixing of a child’s ‘nurse maid elbow’, a type of elbow dislocation, usually doesn’t result in long-term consequences and it’s unlikely the child will face the same issue after they turn five, as the connective tissue around the elbow strengthens.

When it comes to dislocations of the head of the radius bone in the forearm, the nearby posterior interosseous nerve is most frequently injured. Usually, this nerve’s ability to control muscle movement is most affected.

In comparison, dislocations in adults often need surgery to be corrected. Immediate surgical intervention can lead to arthritis and decreased flexibility in the joint. However, if the diagnosis and treatment are delayed, the health consequences could be even more severe. If unaddressed for many years, the head of the radius bone could develop a deformity which would necessitate a more intricate surgical procedure to fix.

Possible Complications When Diagnosed with Radial Head Dislocation

Conditions related to elbow dislocation may include:

- Osteoarthritis

- Chronic pain

- Reduced mobility of the elbow joint

- Radial head deformity if the dislocation remains undetected for a long time

Recovery from Radial Head Dislocation

After having elbow dislocation surgery, the care needed is similar to other surgeries involving the upper body. Generally, a doctor who specializes in the treatment of bones, known as an orthopedic surgeon, will prescribe strong pain medication for a short time. Patients are usually sent home with a splint or brace on their arm, which they should wear for a few weeks. After this time, they can begin specific range of motion exercises as prescribed. Getting physical therapy after the initial weeks can help speed up the recovery and allow the arm and joint to move fully or almost fully again. It’s also important for patients to keep an eye out for any signs of infection as part of their postoperative care.

Preventing Radial Head Dislocation

Kids who’ve previously had a condition called “nursemaid’s elbow” are more likely to experience it again. This risk isn’t because of the initial injury. Instead, it’s related to the structure of a specific arm ligament. This ligament, called the annular ligament, typically strengthens when the child is four or five years old.

The recurrence of nursemaid’s elbow can be triggered by various actions that involve pulling on the child’s arm. Examples include putting on a shirt, lifting or pulling the child by the arm, or catching them by the arm when they’re falling. It’s best to avoid these activities as far as possible when handling young children who’ve previously experienced a nursemaid’s elbow. It’s especially important to be careful until the child reaches the age of five when the annular ligament generally becomes stronger.